As the 2016 race for the presidency heats up absurdly early, we are already experiencing the horror of what the eventual election campaign will look like, and it’s enough to make sane people scratch their eyeballs out. Hillary Clinton, the presumptive Democratic nominee is already under attack by the Republican clown car of nominees as being elitist, out of touch, old, dynastic, dishonest, and untrustworthy. We can be sure it won’t be long before Whitewater, Travelgate, Lewinsky, and god knows what else will be dredged up from her past. The unspeakable crime of being a woman who favors pantsuits is more than the right can bear. It’s going to be an ugly campaign.

As the 2016 race for the presidency heats up absurdly early, we are already experiencing the horror of what the eventual election campaign will look like, and it’s enough to make sane people scratch their eyeballs out. Hillary Clinton, the presumptive Democratic nominee is already under attack by the Republican clown car of nominees as being elitist, out of touch, old, dynastic, dishonest, and untrustworthy. We can be sure it won’t be long before Whitewater, Travelgate, Lewinsky, and god knows what else will be dredged up from her past. The unspeakable crime of being a woman who favors pantsuits is more than the right can bear. It’s going to be an ugly campaign.

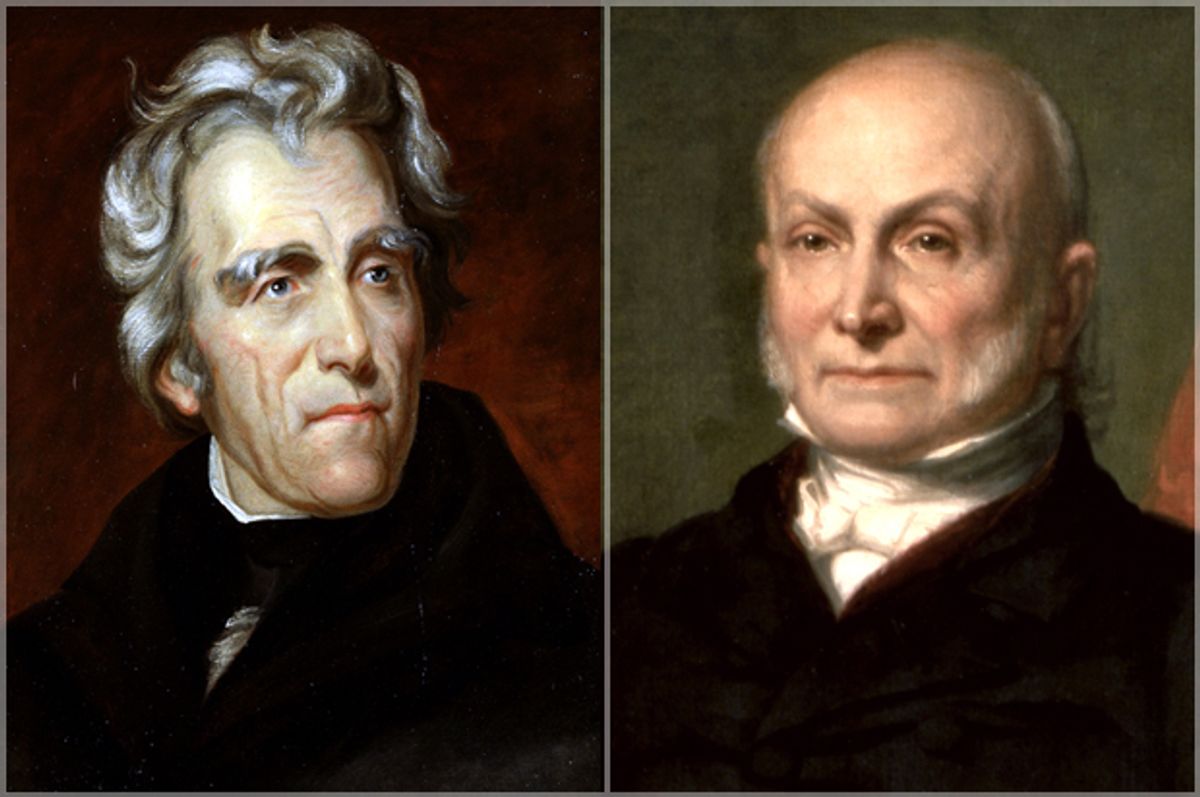

Every four years, the media declares the current election to be the dirtiest in history. While it is true that negative campaigning wins elections, and every campaign does have its share of dirty tricks, no modern presidential campaign can really claim the banner of filthiest ever. Not yet anyway. Because that title belongs to an election none of us witnessed. The dishonor of dirtiest presidential campaign in history goes to the Andrew Jackson/John Quincy Adams contest of 1828.

The previous election of 1824, the first time Jackson and Adams were pitted against each other, set the stage for the 1828 sleaze-fest. Jackson was the nominee of the Democratic Republicans (eventually shortened to Democrats, as we know the party today). The Democrats of this era were more reminiscent of the modern GOP, with a commitment to limited government, individual liberty and states’ rights. Old Hickory, as Jackson was known, was the choice of the common man.

Unlike presidents before Jackson, who were upper class, well schooled and wealthy, Jackson came from humble means. Poor, Southern, orphaned, and occasionally abused as a child, his up-from-the-bootstraps success as a military hero appealed to the masses.

His opponent, John Quincy Adams, was Jackson’s polar opposite. The son of the former president and Founding Father John Adams, was privileged, a world traveler, multi-lingual, and erudite. By the age of 15, he had already worked as a translator in the royal court of Czarina Catherine the Great of Russia.

Jackson squeaked by Adams in 1824 winning the popular vote, but failed to gather the necessary majority of electoral votes. Jackson took the entire Southwest, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the Carolinas, 11 states out of 24. He garnered 43% of the popular vote and 99 electoral votes, more than any other candidate, but not enough. The decision of who would be president fell to the House of Representatives.

There, in what Jackson supporters called the "Corrupt Bargain,” Henry Clay, an influential congressman (and also a presidential candidate that year), threw his support to Adams, and in return, Clay was named Secretary of State once the Adams administration was in place. Jackson’s camp cried foul. The groundwork for the nastiest campaign in American history was laid.

From the start of the John Quincy Adams administration, the Andrew Jackson machine worked behind the scenes lining up support for 1828. The South was Jackson’s natural base, among the rural, the poor, the “common” people. Jackson needed help in the North, and he found his partner in Martin Van Buren. Van Buren was a New York power broker who served as senator while maintaining control over the New York political machine in Albany. A committed Democratic Republican and fervent opponent of the president, Van Buren felt Adams would concentrate power in the federal government. He threw his influence behind Jackson and with that came significant support in the North.

Andrew Jackson had a number of skeletons in his closet that were easy for the Adams camp to exploit in 1828. For one, he had a fierce temper. His violent life included a number of duels, one of which, in 1806, ended with the death of his opponent (Jackson remains the only president ever to kill a man in a duel). For another, General Jackson, during the War of 1812, had ordered the execution of six men in his militia who were accused of desertion. This incident haunted him in the election, when an Adams supporter, a printer named John Binns, produced and disseminated a poster featuring six black coffins, intimating that Jackson had murdered the militiamen.

Echoing the modern-day 2004 election, when military hero John Kerry was “swift-boated” by George W. Bush, Jackson’s military successes were turned against him. He was accused of disobeying direct orders when he successfully subdued Spanish Florida in 1819, the equivalent of invading a foreign county. In New Orleans during the War of 1812, his declaration of martial law, and his harsh military rule, became a campaign issue because it had actually happened after the war was over.

Jackson’s marriage was another weapon Adams used in the election. Rachel Jackson had been married—by most accounts unhappily—before meeting Jackson. Rachel divorced her first husband, but the Adams campaign insinuated that her divorce had not gone through at the time she married Jackson. Jackson was accused of adultery and living in sin. Rachel was accused of bigamy. These were no small accusations in 1828. The Washington Daily National Journal, which supported Adams, published a pamphlet claiming that Jackson had fought Rachel’s husband, chased him away and stolen his wife.

John Quincy Adams had his own problems. Having been elected as a minority president, he had worked tirelessly to legitimize his administration, supporting federal programs to improve national transportation infrastructure and protective tariffs to safeguard American industry. This left him open to accusations from Democrats of corruption and federal overreach. The South, especially, felt that the tariffs penalized them in order to prop up northern industry. The Jacksonians labeled protective tariffs on iron, hemp and flax as the “Tariff of Abominations.”

Adams had begun his career working for an American diplomat in Russia, eventually becoming America’s ambassador to Russia. The Jackson people spread the rumor that Adams had provided the Russian czar with the sexual services of an American woman. Adams, they claimed, was nothing more than a pimp and his success in Russia was a result of his pimping prowess. Adams was even accused of gambling, of having a pool table in the White House that he paid for with government money.

As the mud flew back and forth, the campaign got so nasty that Adams completely withdrew from any active participation, feeling that he was above such campaign filth. One Adams newspaper even wrote, "General Jackson's mother was a common prostitute, brought to this country by the British soldiers! She afterward married a mulatto man, with whom she had several children, of which number General Jackson is one!"

Jackson, on the other hand, was so offended that he became even more involved, instructing his supporters how to respond to accusations from the Adams handlers. Paralleling the 2000 Gore/Bush campaign, Jackson, like George W. Bush, was the candidate voters were more comfortable with, the one they most wanted to sit down, have a beer and shoot the breeze with. Adams recognized this himself. In his diary, even before the election took place, he wrote, "[I]n a popularity contest, in a political contest, no man could stand against the Hero of New Orleans.”

In the end, Jackson won easily in 1828, with 56 percent of the vote and 178 electoral votes to Adams' 83.

Like Jimmy Carter, another modern president who lost his bid for a second term, John Quincy Adams found a second life after his presidency. Stung badly, but still eager to serve his country, Adams won a seat as a congressman representing Massachusetts, and had an illustrious second career in the House. He became a hero to abolitionists, arguing against the institution of slavery. In 1841, he defended 39 African captives in the famous Amistad case, which he won before a mostly pro-slavery Supreme Court.

Sadly, the sleazy campaign had a more serious effect on Jackson’s life. The unending accusations of adultery and bigamy took their toll on Rachel Jackson, who, shortly after her husband’s election, sickened and died, mere days before they were to head to Washington to begin his presidency. Jackson was devastated. He never wavered from the belief that his beloved Rachel was killed by the attacks from the Adams’ camp. On the day he was inaugurated, he refused to make the traditional visit to the outgoing president. “Any man who would permit a public journal, under his control, to assault the reputation of a respectable female, much less the wife of his rival and competitor for first office in the world was not entitled to the respect of any honorable man."

Shares