Three songs into the show, the house lights still on, the time had come for “Dire Wolf,” but with a perverse twist no one had anticipated. Twenty-five years had passed since the Dead had recorded that song at Pacific High studio. They’d played it innumerable times since, occasionally slowing it down a half step. But tonight, in the middle of Indiana, they again injected it with the crisp, merry gait of the recorded version, and even the song’s refrain harked back to its original impending-death inspiration. “Please, don’t murder me,” Jerry Garcia sang again, now in a voice weathered by age and abuse, as cops pivoted their heads, hoping to catch sight of the man who’d vowed to kill Garcia before the night was over.

Along with the likes of Alpine Valley Music Theatre in Wisconsin, the Deer Creek Music Center had become a destination spot, a revered haven, for the Dead and their fans alike. Springing up amid cornfields and cow pastures a half-hour north of Indianapolis, the amphitheater was, like the band, an enclave unto itself. Out there the straight world never felt so distant. Although the Dead had played Deer Creek six times before without major incident, tonight began on a sour note. On their way from their hotel (north of Indianapolis) to the venue word filtered down to band and its management: a death threat had been called in to Deer Creek. Similar calls and warnings had arrived before, but this one felt creepier. An anonymous person had called local police claiming to have overheard the distraught father of a young female Deadhead. The information was unclear, but the implication was that the girl couldn’t be found and had run off on the road with them, and that the father was planning to attend the show and shoot Garcia.

Huddling backstage with the head of security, the band grappled with what to do. Verifying the threat was difficult, but Phil Lesh, the most immediately concerned because his family was there, made the case for canceling the show and heading out. “I was not going to stand up there and be a target,” he recalls. But Garcia brushed it off, saying he’d dealt with crazies before and wouldn’t let this one stop him. “Would you sacrifice yourself for the music?” Mickey Hart recalls of that night. “All those things run around in your brain. But I remember joking, ‘Jerry, could you move over six inches onstage? At least I’ll make it!’ We were screaming laughing. The decision was made and everyone came around. We were worried, of course, but we didn’t want some lunatic to shut us down.” Indiana state police made their way into the crowd and the stage pit; there they were joined by other Dead employees, including publicist Dennis McNally and Steve Marcus of Grateful Dead Ticket Sales, all nervously glancing around for . . . something. No one knew what the supposed shooter looked or dressed like, and no one even knew for sure whether the threat was real. But they weren’t about to take any chances.

Ironically, the show opened with “Here Comes Sunshine,” the twinkling kaleidoscope of a song that was dropped from the repertoire after 1974 but had returned starting in 1992. At one point in the show a piece of electronics gear began misbehaving, and keyboard technician Bob Bralove, who usually stood behind the keyboards or drum riser, was forced to walk to the front of the stage to fix it. He’d performed the task dozens if not hundreds of times before, but never before had he felt as if a bull’s eye was plastered on his chest. “You could feel it,” he says. “This was normally the place that was always safe and you felt the love from the audience. But all of a sudden I’m realizing I’m standing next to the guy they said they wanted to kill. It was very, very intense.” After tending to the repair Bralove quickly retreated back to the darkened part of the stage.

For years they’d defied the odds; so many times they’d been written off creatively, physically, or economically, only to return, sometimes as vital as before. But the last few months had made even those closest and most loyal to the Dead wonder whether they, Garcia especially, would be able to pull back from the darkness. During a set break Garcia called his loyal driver, Leon Day. “I had a threat on my life,” he told him. Day joked back: “I got your back—you got mine?”

Still, Garcia sounded unnerved. “He’d gotten threats before,” Day says, “but for some reason this one seemed to hit home.” The driver made plans to pick up Garcia at the airport when the tour finished in a few more days. Then, as Garcia was beginning to tell members of his inner circle, he would finally consider rest, recuperation, maybe even a serious stint in rehab. Thirty years after the Warlocks had played Magoo’s pizza parlor, they all needed to reassess what everything had come to.

*

By the early nineties the members of the Dead weren’t seeing much of each other off the road; they were business partners but rarely socialized. “When they got home they shut each other out a little bit after so many years of working together,” says Garcia’s daughter Trixie, who stayed in the Bay Area and went to community college after Garcia and Mountain Girl split up again post-Manasha (Mountain Girl returned to Oregon). “Typically Jerry would be pretty exhausted for a week after a tour. Almost catatonic. He wanted a simple existence. He didn’t want to go anywhere or have visitors. Very shuttered.”

The band’s schedule was set in particularly hardened concrete: tours each spring, summer, and fall, with spring shows in the Carolinas and up through New York; summer stadium shows, then the multiple fall runs at arenas in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. Specific dates, even venues, were reserved as much as a year in advance. The labor paid off: in 1993, according to the concert-industry outlet Pollstar, the band was the top-earning touring act, pulling in over $45 million, and the following year the number jumped to $52 million. Tickets were almost always sold out in advance, thanks to a mailing list that had started in the early seventies with 26,000 names and now including more than 200,000. After Garcia’s collapse in 1992 additional shows had to be added the following year to compensate for the loss in revenue. The band had had to deal with another crippling blow in October 1991, when Bill Graham died in a helicopter crash.

As the band well knew, their success came with a Faustian bargain. Grateful Dead Productions now employed thirty people (including the band), some who’d worked for the Dead for decades. Another fifteen worked at Grateful Dead Merchandising, and GDTS (Grateful Dead Ticket Sales) was home to another few dozen. In 1973 total monthly salaries for the band were $60,769. By 1995 the band’s monthly overhead, including salaries, rent, and insurance, could top $750,000 when the Dead toured stadiums (less when they were doing indoor shed or arena tours). “We were no longer just a band,” Hart says. “We had a payroll and families. We weren’t getting that much money; we were spreading it around. We couldn’t stop. We were a snake eating its tail. There was no way for us to take a rest. We were locked into tour, tour, tour. I’m sure I wanted to take a break, but there were no options.” Garcia had a high overhead himself, which included monthly $20,833 payments to Mountain Girl from their divorce. The couple had amicably met behind closed doors at the office of lawyer David Hellman in 1993. When Hellman questioned the number Mountain Girl proposed, Garcia said he was fine with it.

As they settled into their late forties and mid-fifties, some health issues dogged them. Realizing it was time to leave Front Street in favor of more professional digs, the Dead decided to buy a former Coca-Cola building on Bel Marin Keys Boulevard in Novato. At over thirty thousand square feet, the space was huge and could accommodate a recording studio more advanced than the one at Front Street. According to McNally, the band members were required to take physicals for insurance on the property, and what came back were diagnoses of high cholesterol, hepatitis, and other ailments. Polygram, which owned part of Dead promoter John Scher’s Metropolitan company, took out a death-and-disability policy on the Dead. The paperwork didn’t stem from overt concerns about the Dead’s well- being; corporate policy dictated that key executives as well as recording artists who had influence over the business had to be insured. In this case only Garcia and Bob Weir were included because someone assumed that the primary lead singers were the key to the Dead’s success.

Garcia—who was using heroin on and off during this period--remained everyone’s concern, especially when his stage performances during 1994 shows grew increasingly erratic and slothful. “The nineties was my least favorite period, because of Jerry’s declining health,” says Hart. “He was missing so many damn notes.” Hart says he soon learned one of the reasons why Garcia was making those mistakes. Garcia told him that due to clogged arteries, he could no longer feel his guitar pick, which was starting to freak him out. Garcia was also grappling with carpal tunnel syndrome and diabetes. At a show at Giants Stadium, most likely in 1994, Bralove watched as the band started “Crazy Fingers” and Garcia began playing the opening riff again and again, as if in an addled loop. “Jerry couldn’t get out of the beginning triplets,” he says. “He got stuck in this groove. I remember thinking, ‘Did he have a stroke?’ I thought, ‘Oh, it could happen this way, where he just keels over in front of forty thousand people.’ There were other times when he was taking solos when I thought, ‘What’s going on? What’s he doing?’ Maybe it was one fret off , so he was a half-step off the whole solo. He was going through some routine—the physiology of it—but not actually listening.”

Bralove would look over and see pained expressions on band members’ faces, especially Lesh. Fans began writing into the Dead office complaining that Garcia was forgetting lyrics. Ever willing to invest in new technology, the Dead began using in-ear monitors that allowed them to press a foot switch and speak to one another without the audience overhearing. Garcia’s impatience now had a vocal outlet: “The chord is A minor,” he was once heard saying in the middle of a song.

Around the country promoters heard the ominous rumors and speculation about Garcia’s health. Shows would often be preceded by a series of unsettling phone calls. “I’d ask, ‘How’s Jerry doing?’” recalls Atlanta promoter Alex Cooley. “They’d say, ‘It’s gonna go—he’s going to play. Just do it.’ There was no show without Jerry, so we relied on people’s words. We were dealing with millions of dollars, and people were giving me verbal okays over the phone. It was scary.” Koplik would tell his team, “Don’t worry about it—it’s going to happen or not happen. You don’t have control over it.” It was about all anyone in his position could say. In one of Garcia’s guitar cases his old friend Laird Grant left a poignant note: “Hey Jerry, please take care of yourself out there. Your friend, Laird.”

Garcia had appeared tired and increasingly disoriented during shows in 1994, but as the band entered its thirtieth year in 1995, his descent became more obvious. Visiting her father at his home in Tiburon during the early months of the year (he and Deborah Koons maintained separate residences), Trixie let herself in and found Garcia lying face down on the bed. When she playfully tickled his feet to wake him up, he leapt up, startled. “He was passed out in the middle of the day on his bed, and he was probably high,” she says, “but I didn’t put it together.” Around the same time, Garcia agreed to be interviewed for a history project, "Silicon Valley: 100 Year Renaissance," produced and directed by John McLaughlin, the Palo Alto native who’d taken drum lessons from Bill Kreutzmann long before. Garcia was friendly and chatty, but with his creased, sagging face, he looked at least twenty years older than he was, and every fifteen to twenty minutes he’d ask for a break to go into the pantry to, as he put it, look for his car keys. Given the rumors around Garcia and his past issues, it was easy enough for the film crew to assume he was taking one substance or another during those breaks.

The perks of the job continued unabated: large homes, BMWs, home studios. On tour the Dead sometimes flew in a private Gulfstream III plane complete with a bar and made-to-order food. But to some friends or intimates Garcia would make his wishes known. Garcia told crew member Kidd Candelario he wanted to move to Italy, sign up for art classes, and only play with the Dead on weekends. “We were so excited,” says Candelario. “That was his dream. He wanted to put the Dead on sabbatical. There was plenty of money to be able to do that.”

The time had come to address not just the machinery of it all, but everything that had built up over the last three decades: the sometimes overwhelming intensity (and devotion) of their fan base, the live-and-let-live philosophy within the band, and, equally important, the way it was affecting the music. At band meetings the thought of shuttering the unwieldy Dead operation and allowing Garcia to regain his health would be brought up. (Garcia canceled the second half of a Garcia Band show in Phoenix in the spring of 1994 after he felt sick backstage.) According to Lesh, a three-point plan was laid out after Garcia’s breakdown in 1992. If the Dead played only Bay Area shows for the rest of that year, they would cut back on salaries and equipment and “hopefully go back to full salaries in January,” according to an internal report. If the concerts didn’t resume at all until December, salaries would be cut in half in November, rather than by one-third (as in the first plan), before eventually returning to normal pay levels. In the third proposal, which assumed the band wouldn’t play at all for the rest of the year, salaries would still be cut, but expenses would be reined in by “laying off everyone except for those necessary to maintain office and operations until we regroup in 1993.”

That outline was the closest the Dead came to mapping out a specific plan of action. Otherwise, band and management would meet in the Dead’s conference room and grapple with if, when, and how to leave the road, at least temporarily. Garcia’s inconsistency onstage—weak performances followed almost immediately by strong ones—also confused matters. (At a show in Albany, New York, shortly before Deer Creek, his guitar had moments of ageless beauty even if Garcia himself—looking drawn and frail, his long white hair drooping forlornly to his shoulders—seemed prematurely aged.) “They talked about it, but they never made a decision to do it and figure out exactly how to do it,” says band accountant Nancy Mallonee. “Jerry felt he was on some kind of assembly line and needed more time at home, and the band knew it was hard on him. But they were stuck in this pattern. They’d laid people off in the seventies, but [the machine] wasn’t nearly as big then.” Recalling similar discussions, Scher says, “There were a couple of times—and, believe me, they were not serious confrontations—if the band said, ‘We’re not going out until you get yourself together,’ he just would have gone out with the Garcia Band. He said, ‘John, I play guitar every single day. I might as well get paid for it.’”

In the meantime road work beckoned, as it always did. When driver Leon Day picked up Garcia for a soundcheck at the Silver Stadium in Vegas in May of 1995, he had to throw pebbles at his boss’s window to get his attention. Finally Garcia came down, looking bedraggled and tired. “Oh, come on, you’ll outlive us all,” Day joked. Garcia replied, “I won’t see the end of the year.”

By the time the band reached Chicago for the last two shows, July 8 and 9, eleven TV crews had arrived to chronicle any further calamities, and Scher flew in from New Jersey after hearing the Deer Creek news. Even though Garcia would sometimes flinch when Scher tried to talk with him about his smoking, Garcia admitted he knew his health was teetering and told Scher he was going to Hawaii after the tour to relax and recuperate. Compared to past conversations, Scher was pleasantly surprised and hopeful, even if the scene around the Dead still appeared shaky. “Things were pretty fractured at that point,” says Scher. “Everyone was a bit on edge and tired of what was going on. It had all gotten out of hand.”

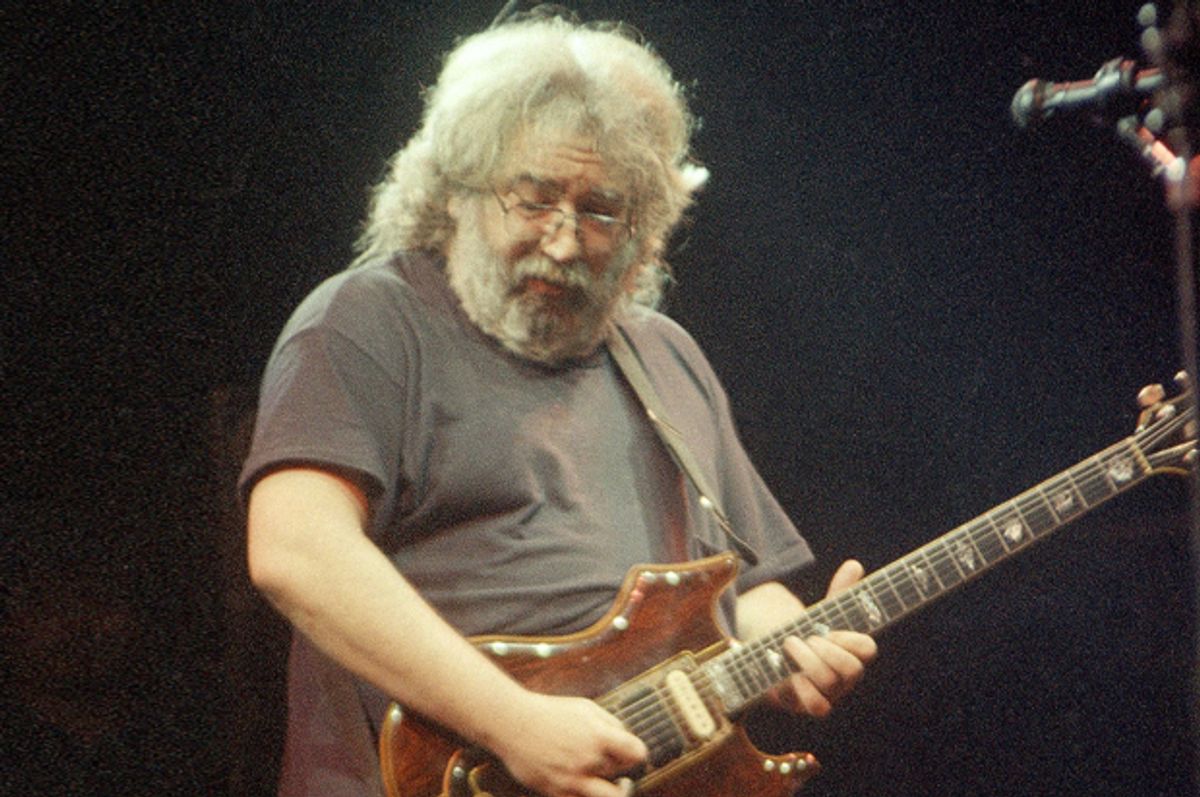

The final night in Chicago, July 9, didn’t feel right from the opening notes—and not only because, thirty years before, a Ouija board in the band’s rented house in Los Angeles had announced that day as some kind of finale. Starting with “Touch of Grey,” Garcia’s voice wavered in and out of key, and the harmonies were shaky. When Garcia peeled off a solo the tone was spry and fluid. Roaring out the “we will get by” refrain at the end of the song, the crowd seemed eager to voice its own positive outlook toward him and the Dead. The rest of the show was typically spotty, but at moments—especially on a version of “Lazy River Road”—Garcia’s voice settled into its deeper, lower register as if he were sinking into a comfortable old sofa. The slower, more elegiac songs were clearly speaking more to Garcia, made jarringly clear to Steve Marcus when he and some coworkers watched closely as their boss sang “So Many Roads,” with its desolate Hunter lyrics about easing one’s soul. “We were looking at each other like, ‘What’s going on with Jerry?’” Marcus says. “He was putting more into that song than we’d seen him do for years.”

As the band ended the show and prepared for an encore, word filtered out through crew walkie-talkies of a double encore: “Black Muddy River” and then, at Lesh’s suggestion for a more upbeat ending to the show and tour, “Box of Rain.” For three decades the band had put itself through a seemingly nonstop cycle of ups and downs: rejuvenation followed by collapse or near-collapse, followed by another renewal. The pattern was as much a part of their story as their music, and it was only natural to assume that the pattern would continue, that Garcia would again rise up.

On the flight back to San Francisco Hart sat next to Garcia and watched as his band mate of twenty-eight years nodded off, falling into a deep sleep, accompanied as always by his thunderous snore. (That peculiarity could be useful: when he fell asleep in hotel rooms on the road it was a way for the organization to tell he wasn’t dead.) At one point in the flight Hart looked over and saw Garcia’s heart literally beating through his T-shirt. “I went, ‘Wow, have I ever seen that before?’” Hart says. “His brave heart was beating on, but that baby was really tired.” After such a difficult run of shows, everyone needed a rest, but no one more than Garcia.

Excerpted and adapted from "So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead" by David Browne. Published by Da Capo Press. Copyright © 2015 by David Browne. Reprinted with permission of the author and publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares