“Then God said, Let us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness; and let them rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over the cattle and over all the earth, and over creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” – Genesis 1:26

“And God blessed them, and God said to them, Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion…” – Genesis 1:27

In June, Pope Francis released a powerful encyclical on human ecology and climate change. The text has been praised by most observers, and rightly so. It contains an urgent message, one that believers and nonbelievers ought to welcome. “The Earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth,” Pope Francis writes. “The exploitation of the planet has already exceeded acceptable limits and we still have not solved the problem of poverty.”

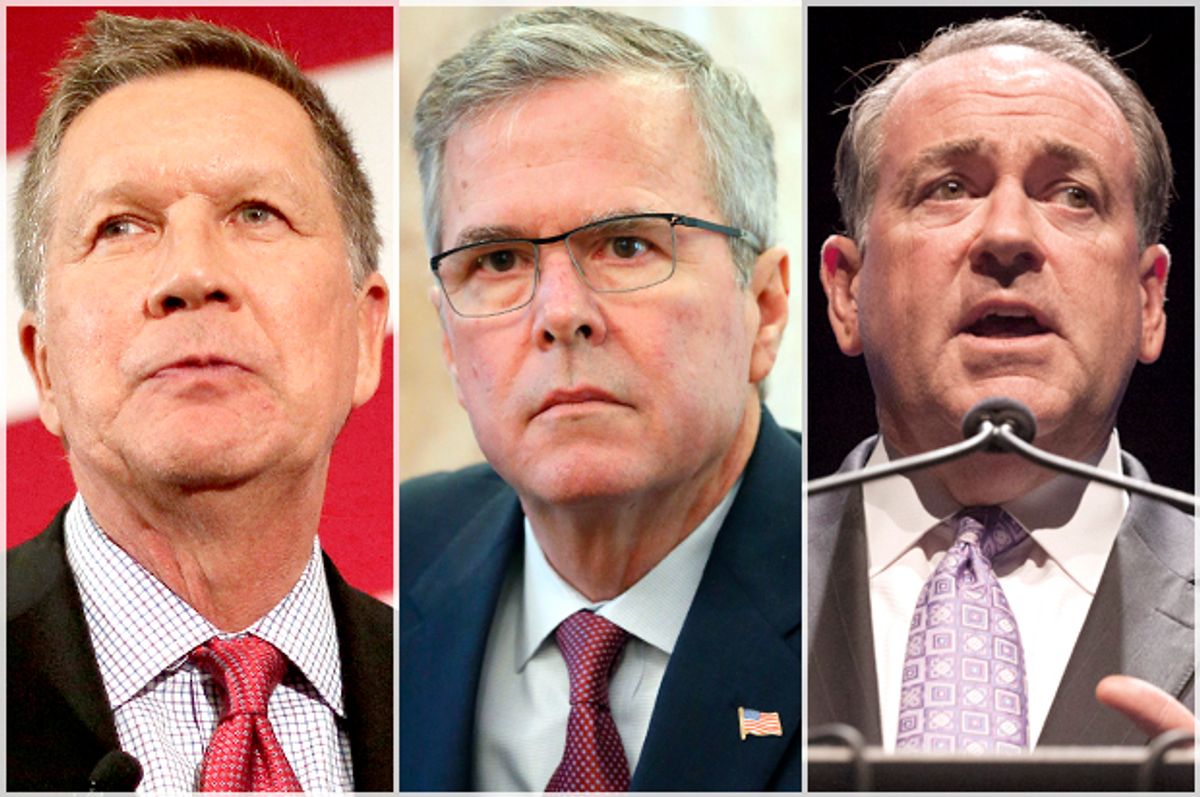

There’s nothing to disagree with in those remarks; indeed, it’s refreshing to hear them from a religious figure of such significance. Frankly, I admire the pope’s willingness to tell the truth, and to do so in the clearest of terms. But the political response to his message, particularly from Christians, has been instructive. GOP candidates, notably Jeb Bush and Rick Santorum, have roundly rejected the pope’s call to action, despite being Catholics. “I don’t get economic policy from my bishops or my cardinal or my pope,” Bush said. “I think religion ought to be about making us better as people and less about things that end up getting in the political realm.” Santorum dismissed the encyclical on similar grounds: “The church has gotten it wrong a few times on science, and I think that we probably are better off leaving science to the scientists.”

These remarks tell us what we already knew about Republicans: They’re hypocrites. After all, this is the party that continuously conflates religion with politics, and decided, as a matter of strategy, to make faith a central part of their political platform. And Republicans, it’s worth remembering, are the ones who reject science as a basis for public policy, who shirk scientific consensus when it runs counter to their agenda. Now they want to leave the “science to the scientists?” Unbelievable.

There is another aspect of this story, however, one that will receive far less coverage than Republican hypocrisy. Our conversation about economics and the environment is plagued, needlessly, by religious dogma. However well intentioned, the pope’s environmentalism highlights a caustic conceit at the core of Judeo-Christian theology. A common conviction among Christians – and all Abrahamic faiths – is that human beings are special; that we’re above nature and the rest of creation. This sentiment was expressed almost perfectly by Gov. John Kasich, a committed Christian and the current governor of Ohio. When asked about the pope’s encyclical, Kasich said “The environment was given to us by the Lord, and it needs to be taken care of; and it shouldn’t be worshipped – that’s called pantheism.”

As the above passages from Genesis show, there is a biblical basis for this belief. But it’s time for Christians – and all believers – to reject it. This idea that the earth is our plaything, that it was made with us in mind, is human hubris at its full height. Human beings are of the earth, not above or beyond it. We’re subject to the same laws of nature that all living things are – and we’ll pass away just as swiftly if we forget that.

It’s true that one can be both a Christian and an environmentalist. And many Christians will say – as the pope does – that God gave us stewardship over the earth; that we’re compelled to care for His creation. But this, too, is wrong. We’re stewards only of the world we’ve created, the world we’ve built. Stewardship of the planet implies a higher rule. Whether we acknowledge it or not, the earth rules over us; and it’s indifference to human affairs becomes more apparent by the day.

The choice, then, is not whether to care for the planet God gave us. The real choice is whether to respect or rape the physical system on which our lives depend. How we see ourselves in relation to that system matters. The planet is not something to be domesticated, to be conquered or exploited. The problem with the view that creation was “given to us” (as the pope put it) is that it validates a whole host of misconceptions – about our place in the cosmos, about our role in nature, and about our obligations to other creatures.

The authors of the Bible tell us that we have dominion “over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over the cattle and over all the earth.” These are not the inerrant words of God; they are the fallible words of fallible human beings, who knew nothing of the world they inhabited. Had they any knowledge of biology or physics or chemistry, they would have known that humans have no special role in creation; that, in fact, microorganisms have dominion over our bare bodies; and that we live perilously on a remote planet in a tiny solar system at the edge of an exploding universe.

These are humbling truths. They remind us of our smallness, of our dependency on nature. Although I applaud the pope for his courage, it would have been far better for him to say in plain terms what we all know to be true: The planet doesn’t belong to us. He says, rightly, that the earth is our home, but his defense of the dominion mandate suggests that we’re entitled to it.

Human existence is conditional. Earth is our home, but only so long as we respect it. This is easier to do if we accept our own insignificance, if we admit, finally, that the earth wasn’t made for us, and that we have a duty to defend it against human vanity and greed. The pope’s appeal to believers is a step in the right direction, but it doesn’t go far enough.

Shares