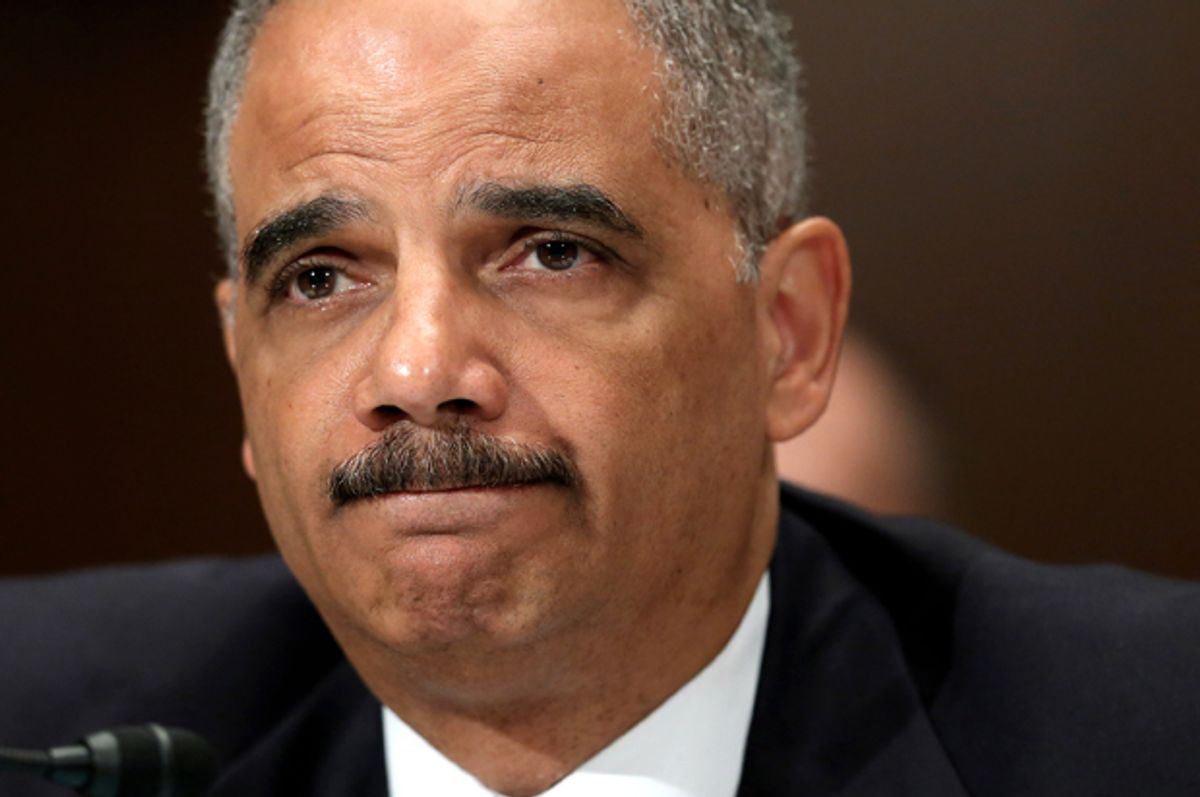

If Las Vegas took bets on whether recently departed Attorney General Eric Holder would return to corporate law firm Covington & Burling, the casinos would have run out of money faster than Greek banks. Newborn infants could have guessed at a homecoming for the former partner at Covington from 2001 to 2009. Last year, Holder bought a condo 300 feet from the firm’s headquarters. The National Law Journal headlined the news, “Holder’s Return to Covington Was Six Years in the Making,” as if acting as the nation’s top law enforcement officer was a temp gig. They even kept an 11th-floor corner office empty for his return.

If we had a more aggressive media, this would be an enormous scandal, more than the decamping of former Obama Administration officials to places like Uber and Amazon. That's because practically no law firm has done more to protect Wall Street executives from the consequences of their criminal activities than Covington & Burling. Their roster of clients includes every mega-bank in America: JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, Bank of America. Yet Holder has joined several of his ex-employees there, creating a shadow Justice Department and an unquestionable conflict of interest. In fact, given the pathetic fashion in which DoJ limited punishment for those who caused the greatest economic meltdown in 80 years, Holder’s new job looks a lot like his old job.

You could actually make a plausible argument that Covington & Burling bears responsibility for the Great Recession: In the late 1990s, Covington lawyers drafted the legal justification for MERS, the private electronic database that facilitated mortgage-backed securities trading. MERS saved banks from having to submit documents and fees with county land recording offices each time they transferred mortgages. So it’s unlikely you would have seen mortgage securitization at such a high volume without MERS, and by proxy, without those legal opinions. Of course, securitization drove subprime lending, the housing bubble, its eventual crash and the financial meltdown that followed. Though evidence pointed to MERS’ implication in the mass document fraud scandal that infected the foreclosure process, former Covington lawyer Holder never prosecuted them, and now he’s back with the old team.

Covington’s real meal ticket is white-collar defense. They literally promote their aptitude in getting bank clients off the hook in marketing materials. I wrote in Salon last March about the firm’s boasting, in a cover story in the trade publication American Lawyer, about avoiding jail sentences and reducing cash penalties for executives at companies like IndyMac and Charles Schwab. Included in the praiseworthy article is Lanny Breuer, who ran the Justice Department’s criminal division under Holder. Breuer, a vice chairman at Covington, vowed not to represent companies under Justice Department investigation, but his presence in a marketing document specifically wooing bank clients is clear: Sign up with Covington, and you get access to insiders at the highest level.

That’s precisely Eric Holder’s value to the firm. He’ll never end up as lead litigation counsel for Citigroup, and he can’t be involved in any cases dating back to his Justice Department tenure for two years. But he’ll be able to advise behind the scenes, a compelling prospect for banks in trouble. As we have seen over the last decade, relationships and influence matter more than the letter of the law in determining whether white-collar criminals face justice.

Holder, who Covington partners voted to bring back unanimously, gave himself away to the National Law Journal by comparing his post-Justice Department career to former Carter Administration Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti. After his tenure, Civiletti also rotated into private practice for the high-powered firm Venable, and was known around Washington as the first lawyer to bill $1,000 an hour for his services.

So this is a money hustle, using the knowledge gleaned from inside government to assist corporate clients. Holder made $2.5 million in his last year at Covington, and the firm actually said out loud that they see him as a “rainmaker.” The head of Covington’s management committee told the Wall Street Journal that Holder would be a “strategic architect” for institutions looking to navigate “a major investigatory matter or perhaps a crisis-management situation.” Holder pronounced himself eager to make money for the firm, and wants to be “a player” in litigation. There’s no mystery here: Holder will be a fixer, an insider looking to help corporations beat the rap.

Hilariously, Holder seems to think he took an “appropriately aggressive” stance against Wall Street while at DoJ, one that might risk his relationship with future clients. I’m not sure that even needs to be rebutted. Holder’s conduct in prosecuting financial fraud was so embarrassing that by the end I would have preferred he just stopped trying. Not only did the public relations maneuvers masquerading as crackdowns not fool anyone, they actually harmed the concept of justice. They normalized the idea that big banks could just buy their way out of trouble, cutting prosecutors in on their ill-gotten profits.

And we’re all still waiting for anyone at a high level in the financial industry to be marched out of his office in handcuffs, nearly a year after Holder said at New York University, “We expect to bring charges in the coming months.” Maybe he was talking about criminal charges for corporations, which the Justice Department is now willing to do after having eliminated any consequences for a guilty plea. If Holder thinks his record is aggressive, I’d hate to see what he considers nonchalant.

Whether inside or outside government, Holder remained the same cautious corporate lawyer, determined not to mess up future employment opportunities. As Deputy Attorney General under Bill Clinton in 1999, he wrote the infamous “collateral consequences” memo, arguing that prosecutors should take what might happen to ordinary workers into account when they decide to charge large corporations (of course, that doesn’t explain why DoJ doesn’t charge corporate officers). Then he went to work for corporations who used that memo as a shield. Then he rotated back to DoJ, where his actions on financial fraud spawned the phrase “too big to jail.” Now he’s back to aiding corporate executives on the other side of the negotiating table.

Holder is at least the sixth former Justice Department official who landed at Covington after leaving law enforcement. In addition to Breuer, Mythili Raman, who also ran the criminal division, went to Covington, as did partner Steven Fagell and special counsels Daniel Suleiman and Aaron Lewis. Holder’s Justice Department appears to have been a farm team for white-collar criminal defense, where the money gets made protecting illicit corporate actors.

Corporate law firms love to hire people with personal knowledge of the rules and how to get around them, and relationships with those who remain inside government. A plum white-collar defense position is a final payback to regulators and law enforcement officials who don’t get too out of line and keep the tender fannies of corporate titans out of prison. As long as they play ball and prove their future worth, they can cash in. I’d wish Eric Holder good luck, but I’m pretty sure he doesn’t need it.

Shares