Comedy has always been an inherently political art form, but in the last decade or two, that inherent quality has become more and more overt. You can probably credit (or blame) “The Daily Show With Jon Stewart” for that. Humor, especially used as a liberal coping mechanism on Comedy Central, became not just a subversive, provocative free-for-all but a form of critique with its own agenda. In our current comedy landscape, comedy is feminist or sexist; race-conscious or racist; queer-centered or homophobic. As tiresome as the comedians who complain about “P.C.” culture are, there’s something flawed about these binary qualifiers, too; though comedy can be is political, topical, and pointed, it’s an art closer to poetry than to critique.

Last week, in an excellent piece for the New Republic, Silpa Kovvali took apart the controversy around comedian Amy Schumer bit “Urban Fitters,” observing that comedy often blurs the line between mocking the use of a stereotype and reinforcing the conventions of said stereotype.

At its best, comedy manages to do both: drawing mainstream attention to peripheral causes and changing minds en masse. It is perhaps because Schumer has continually, deftly reached these heights that she thinks the forces aren’t in opposition. A lot of the time, though, they conflict; it's far more difficult to make people laugh by challenging norms than by reinforcing them. The problem is that the laughter sounds the same either way.

When Schumer says that she enjoys people laughing with and at her what she means is that she enjoys people laughing with her and at the “irreverent idiot” she plays in many of her sketches. That tenuous distinction is what drove Dave Chapelle out of comedy: Were audiences laughing at the stereotypes his characters embodied, or were they laughing at the people those stereotypes were used to demean?

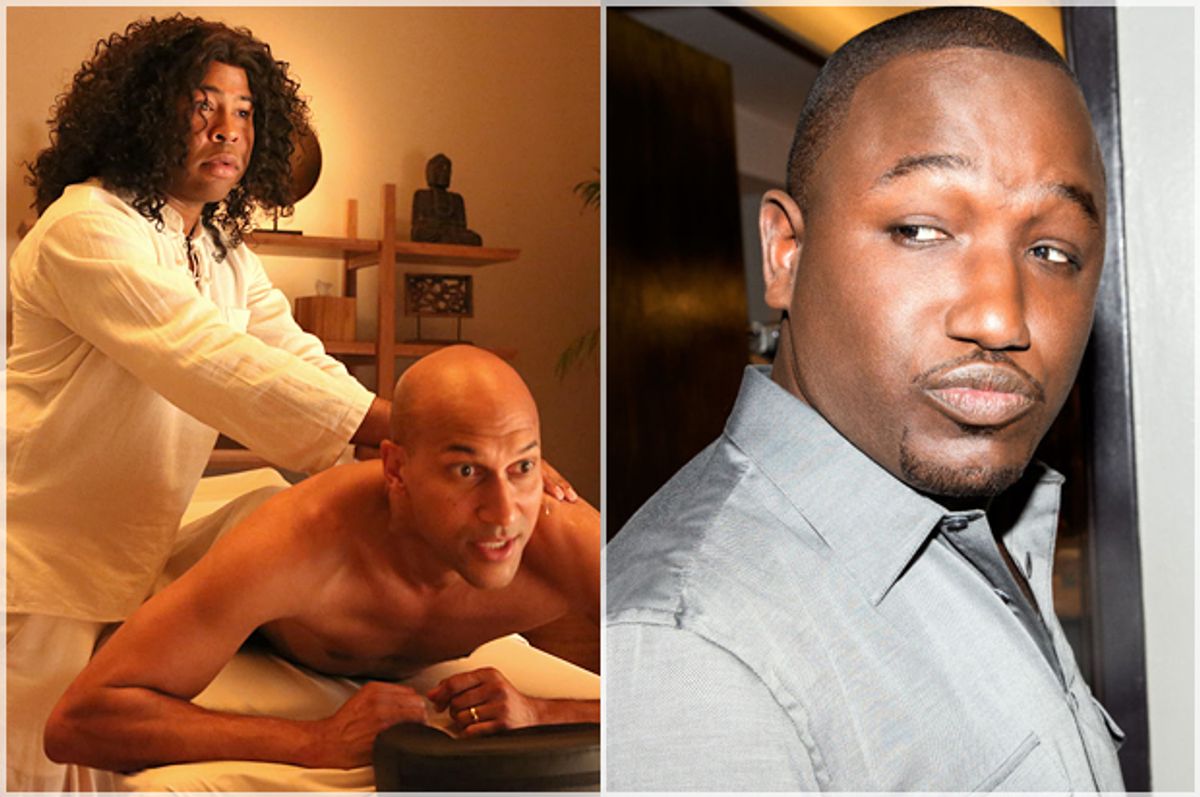

As Kovvali identifies, if these are concerns for comedians of every stripe, they’re particularly on the line for black comedians. This article returned to me while watching the first three episodes of “Key & Peele”’s latest run, premiering tonight on Comedy Central (“Inside Amy Schumer” concluded its explosive third season last night). The sketch duo’s complicated appropriation and layering of identities has long been what makes them so compulsively watchable; as a pair of biracial men, they are both acutely aware of the subtle politics of code-switching. In many of their episodes, including these first few back from their season-four hiatus, Keegan-Michael Key plays both a white man and a black one, while Jordan Peele effortlessly assumes the guise of both a man and a woman. As Emily Nussbaum of the New Yorker wrote about the pair in 2013, their ability to sink into different guises is part of their comic genius: “Hard to say if this is punching up, down, or sideways, but it’s the show’s greatest strength: making specific the men the culture treats as indistinguishable.”

In this fourth season, Key and Peele distinguish themselves from other comedians on-air by being palpably relaxed; the pair has no histrionic energy, and nothing in particular to prove. What stands out is their continued enthusiasm in playing characters that are revealed to be increasingly outlandish as the sketches go on—aggressively one-upping football players; airplane passengers way too committed to responding to threats from imagined terrorists; and two monochromatically attired intellectuals who make a soulful case for staying educated about menstrual health. But—and this is notable mostly for being different from other shows on the same network—there’s also a little bit of quiet removal from the audience. The first three seasons engaged with each sketch in front of a studio audience; this season, “Key & Peele” opts for chatting in a car driving through the desert. It’s an isolation of solace, a distance, perhaps, from the otherwise inevitable conversation that is now everywhere in this country, about whether or not black lives matter—perhaps because that topic is so perennially exhausting. A sense of thwartedness comes through in a few sketches: Obama’s anger translator returns, only to be confronted with, and almost cowed by, Hillary Clinton’s anger translator. The leads’ over-enthusiastic terrorist-hunters end up implicating the innocent black man sitting with them on the plane.

And it what is likely to be the most talked-about sketch, Key—in whiteface—plays a police officer who can’t stop shooting black men, mistaking any prop in their hands for a lethal weapon.

It is funny, eventually. But at first it is just awful. A teenage boy holding a popsicle is gunned down, to the point where you can see his crumpled body on the ground. The setups become more and more absurd, the juxtapositions, more and more ridiculous, and eventually the cop is confronted by the (black) police chief, played by Peele. As far as “Key And Peele” sketches go, it’s almost restrained: This is a show characterized by a conceit being stretched and stretched to the point of absurd oblivion. But the conceit of this sketch is a little different; instead of extending to absurdity, it offers up the idea that this problem, this plague against bodies like their own, is absurd to begin with.

Along with the remainder of the fourth season of “Key & Peele,” Comedy Central is also debuting “Why?” with comedian Hannibal Buress. Buress broke out as a supporting character in “Broad City” but then made national headlines when his stand-up was inadvertently the spark that set off the most damning round of sexual assault allegations against Bill Cosby. Unlike both Key and Peele, Buress is a comedian more attuned to stand-up—and, failing that, a comedian able to communicate an awful lot of pathos in his comic characters. As Lincoln on “Broad City,” he’s soulful; in his appearance on Vimeo’s “High Maintenance,” he communicates a quiet despair about how he’s perceived that doesn’t need to be further named. And yet we still name him a comedian; rueful laughter is still laughter.

Buress’ show “Why?” isn’t sketch, it’s topical; each episode is taped the night before. In this 90-second long promo for the show, Buress digresses from his scripted plug to go on a long rant at the (mostly white) crew about how they did not follow his instructions on what to wear to the set. (He requested Hawaiian shirts.) The promo has overtones of that kind of behind-the-scenes video that goes viral, one that films an actor’s meltdown over something minor. Buress also plays with that notion of black anger that “Key And Peele” highlights in their “anger translator” sketches. Nothing he says is particularly funny; you kind of have to know that he is Hannibal Buress in order to locate the inanity of the rant. Especially when he says: “If Amy Schumer said that shit—I bet everybody in here would be wearing a Hawaiian shirt, if Amy Schumer said it.”

It’s funny, in an entirely different way from “Key & Peele.” Where the sketch show is somewhat divorced from reality, Buress is in the thick of it; he seems to be anticipating the criticisms of Schumer, in a way that mocks her own white privilege as well as his own easy dismissal of her. He doesn’t break his stand-up persona to ensure that the viewer gets the joke; there is no easily available absurdity to use as a filter between his anger and the audience. It’s engaged in a different way than “Key & Peele,” which is to say, much more consciously.

I cannot say anything more on the topic of Amy Schumer, or what is appropriate in comedy, than what Kovvali and others have already said. After all: How do you describe what is funny? It’s possible to give an individual joke or sketch or bit your own personal acid test—laughter, the metric stand-up comedians use to gauge whether or not they’re making it through a set. But there are many different kinds of laughter, including the silent kind; and often, what’s funny at the time isn’t funny at all the next time around. Comedy is an art form highly dependent on context and delivery, one where Amy Schumer’s Twitter account is entirely irrelevant to the mood of the audience at the MTV Movie Awards, and both of those are equally irrelevant to the audience member watching “Inside Amy Schumer” on TV.

But what seems to endure, more than strident controversy, is when humor is brave, resourceful, and committed to expressing something that is far more often viscerally felt than verbally named. The greatest comedians can do that on any number of topics—I am still amazed that Louis C.K. made children’s peanut allergies into an uproariously funny set about humanity’s foibles when it comes to parenting. Naming stereotypes may be briefly funny, and a cheap shot might land, but neither lives on in the minds of its listeners as glorious.

The other piece of news much-discussed over the long weekend was in fact an excerpt from an upcoming book: A piece of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between The World And Me,” released in the Atlantic with the title, “Letter To My Son.” Coates is the best living writer on race relations—and specifically, black/white race relations—in this country, and perhaps on the planet; and his words are marked, always, by an incredible sense of history, scale, and brutal, hard fact. He writes: “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body—it is heritage.” He writes: “You have been cast into a race in which the wind is always at your face and the hounds are always at your heels.” He concludes: “I would have you be a conscious citizen of this terrible and beautiful world.”

“Key & Peele” and “Why?” will directly precede Trevor Noah’s ascendancy to the host’s chair of “The Daily Show” (September 28). An hour of programming hosted by black men every Wednesday will make way for an hour of programming hosted by black men every night, as “The Daily Show” will be followed by “The Nightly Show With Larry Wilmore.” Either way, it’s bold, in a landscape where black men are too often treated as disposable, due to disease, incarceration, or homicide. It’s possible—and heartening—to see these different men spin humor, the most sophisticated defense mechanism, out of such awful facts. It’s a reminder that our individual senses of humor are an inalienable right that are not easily taken from us, even in confinement or under duress. The term “gallows humor” confirms it: Laughter is the last privilege left to the condemned. Privilege, and perhaps, a weapon; perhaps a tool, in the form of a half-hour program. Four half-hour segments of gallows humor, to make the executioner laugh, pause, stay their hand.

Shares