President Obama’s policies of easing economic restrictions on Cuba and normalizing diplomatic relations with the communist island nation are still in the early stages, but they’ve already provided one laudable political victory – they’ve forced Republican presidential candidate and Marco Rubio to stomp all over his own “youthful candidate with ideas from the future” campaign theme.

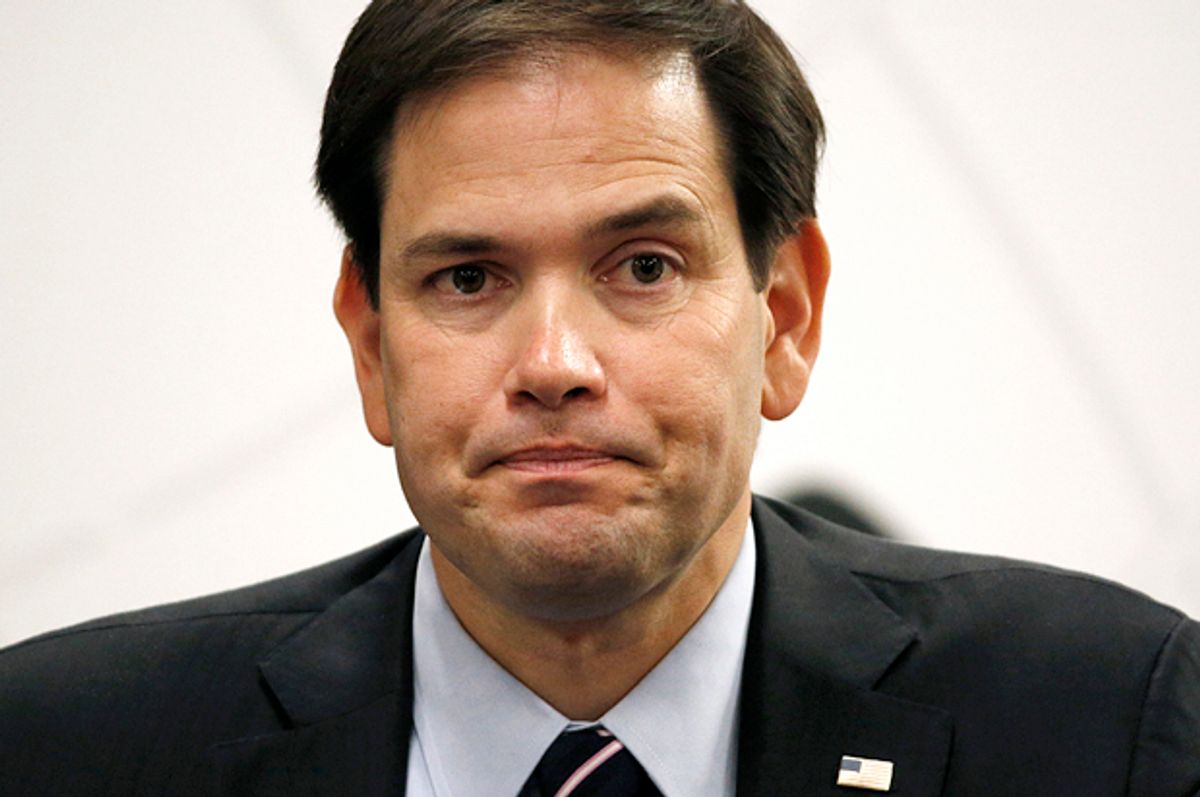

Rubio, a Florida Republican of Cuban descent, is a hardliner when it comes to Cuba, and no candidate has been more critical of the Obama administration’s changes to the country’s longstanding Cuba policy of economic and diplomatic isolation. Yesterday the New York Times published an op-ed by Rubio attacking the Obama administration and advocating that the U.S. “reinforce our longstanding policy” towards Cuba:

When President Obama announced the formal re-establishment of diplomatic relations with Cuba last week, he criticized the supposed failures of United States policy towards Cuba, which, Mr. Obama said, “hasn’t worked for 50 years.”

The reality of course is that American policy is no more to blame for Cuba’s economic and political problems than it was for the Soviet Union’s bread lines or for the fact that tens of millions of Chinese still live in poverty.

As Jonathan Chait ably demonstrates, Rubio comes nowhere close to having a point here. The “supposed failure” the president and the legions of other Cuba policy critics refer to is the fact that the Castro regime remains in power despite the promises of countless politicians over the years that the Cuba embargo was this close to dislodging Fidel. And Rubio counts himself among those who retain faith that our Cold War-vintage Cuba policy – which he calls “difficult” – will bear fruit if we just give it a little more time. “It is unfortunate that, after taking a strong if difficult moral stance for many years,” Rubio concludes, “we are now empowering those who deny the Cubans their wish to be free and prosperous.”

I find this thoroughly hilarious given that Rubio’s entire candidacy is premised on the notion that he is the next-generation leader who will bring new ideas to the White House that will seize the future, or whatever. “Just yesterday, a leader from yesterday began a campaign for President by promising to take us back to yesterday,” Rubio put it in his announcement speech, taking a shot at Hillary Clinton. “But yesterday is over, and we are never going back.”

Except we are going back when it comes to Cuba, apparently. Rubio’s Cuba policy is borrowed from a bipartisan group of Cuba hawks from previous congresses who shared his unshakeable faith in embargo and isolation right up to the point that they left office and/or died. Let’s take a look at what they said back then, which underscores just how ridiculous Rubio is being now.

One of the longstanding proponents of embargo and isolation was former Sen. Connie Mack, Republican of Florida, who spent years pushing for tighter sanctions on Cuba and promising that they would lead to the end of the Castro regime. In March 1990, as eastern European countries were breaking free from Soviet influence, Mack confidently predicted that “Castro es el próximo” (“Castro is next”) and that “we will tighten that noose, day by day, until freedom is restored in Cuba.” Mack was joined in his optimism by his Democratic counterpart, Sen. Bob Graham of Florida, who said in June 1990 that “U.S. policy should be one of increasing the isolation of Cuba from the rest of the world toward the end of accelerating change there.” According to Graham: “Basically, the Soviet Union represents the last cord of the life-support system Cuba has. If that cord is pulled, then I think the collapse becomes even more imminent.”

The downfall of Soviet Russia sparked a flurry of anti-Castro activity in Congress in the early 1990s and a tightening of economic restrictions on Cuba, impelling members of Congress to confidently predict the long-awaited success of the decades-long policy of isolation. “The foot is heavier on the throat of Fidel Castro,” Mack said in October 1990 after the House and Senate agreed to legislation he sponsored banning foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies from trading with Cuba.

In 1995, Congress took up the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, which sought to bump up sanctions on the Castro regime and declared support for regime change in the country. While debating the bill on the House floor in September 1995, former Rep. Peter Deutsch, Democrat of Florida, said “the reality is that Castro is holding on by his fingernails, barely holding on by his fingernails.” Robert Torricelli, then a Democratic representative from New Jersey, was equally blunt. “This bill is an answer, I believe in my heart, maybe the last answer,” he said. “We are in the final stages of a confrontation that has lasted more than a generation. Fidel Castro cannot escape. He cannot survive unless we allow him to.”

The bill languished under opposition from Democrats and the Clinton White House, but in early 1996, after the Cuban government shot down two civilian aircraft piloted by anti-Castro activists, a more stringent version of the legislation passed Congress and was signed into law by Bill Clinton. The chief sponsors of the legislation, Rep. Dan Burton (R-IN) and Sen. Jess Helms (R-SC), used its passage to preemptively declare an end to the Castro regime. “I think this is the last nail in his coffin,” said Burton. “Farewell, Fidel,” quipped Helms.

They were all wrong. But maybe President Rubio will be right. Given enough time, anything is possible.

Shares