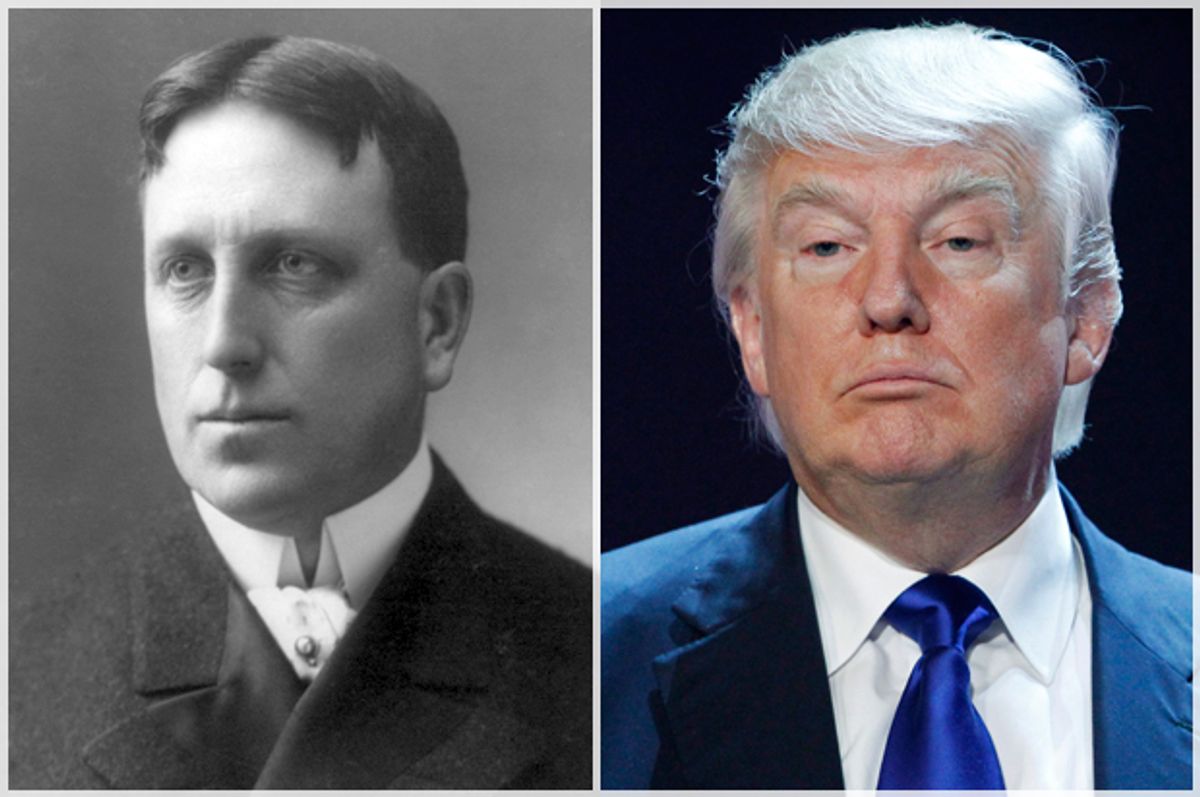

Anyone who has seen Orson Welles’ classic portrayal of the newspaper mogul in "Citizen Kane" knows, at least by reputation, the real-life Kane: William Randolph Hearst. His world-class castle, San Simeon, perched above the California coast, is a popular tourist destination for the many thousands each year who wish for a jaw-dropping glimpse of American opulence. By comparison, anything Donald J. Trump has built as a monument to his ego has to be considered third-rate.

Trump may think he’s one of a kind, but that isn’t quite true -- not in the way he built his empire, and not in the broader political sense either. A century ago, Hearst ran for president and was, for a time, taken seriously. The bicoastal billionaire thrived on the art of the deal and domination in international business. Besides his influential San Francisco and New York newspapers, he expanded his multi-media business by going Hollywood. As a pioneer in the motion picture industry, he produced silent film classics as well as war propaganda, and proved that the entertainment industry could weigh in on, and even direct, national political controversies.

We all know what Trump did to command attention these last few weeks: He went after Mexico, whose illegals were somehow sent north by the Mexican government, and who pose a significant threat to the health and well being of the U.S. Trump may think his Great Wall provides the answer; but he doesn’t go half as far as his more glamorous predecessor did. Will Hearst urged that the government intervene militarily in Mexico, capitalizing on political upheaval there. “There is only one course to pursue,” he editorialized in 1913, “and that is to occupy Mexico and restore it to a state of civilization by means of American men and American methods.” He generalized about the Mexicans as “cunning and unscrupulous,” as he proposed all-out invasion.

Headline grabbing was, literally, Hearst’s business. His combustible personality had already been responsible for the “yellow journalism” that got the U.S. into war in Cuba in 1898. Trump hasn’t done that yet. While “The Donald” tells us China is a subverter of all that is of value to the health of the American economy, “The Chief,” as Hearst was known, accused the same government of setting a subversive example among the key nations with which the U.S. conducted its trade. He attacked the “rich mandarins” of the East who, he said, stood as the model for an across-the-board American business failure.

Indeed, the egocentric Hearst aimed every bit as high as Trump, making noises (as Trump did) about running for mayor of New York City (he almost won) and governor of New York, and making a serious run for president in 1904. He spent millions of his own money in the process, constructing an independent political organization, appealing directly to the people, and dismissing his national competition as lesser men who were barely worth paying attention to. It was as if the election was a referendum on him. Yet he groused about incumbent President Theodore Roosevelt: “He is a creation of newspaper notoriety.” Hearst’s campaign strategist, Arthur Brisbane, said: “The American people, like all people, are interested in PERSONALITY.” Even then they knew.

But here’s the crucial difference between Hearst’s and Trump’s loud efforts to capture the presidency: The earlier billionaire (worth seven times what Forbes says Trump is worth; three times what Trump says Trump is worth) was a more credible populist. He was a staunch union supporter, and said the following: “Wide and equitable distribution of wealth is essential to a nation’s prosperous growth and intellectual development. And that distribution is brought about by the labor union more than any other agency of our civilization.” Yes, he said that while running for president in 1904. Also, “the corporations control the Democratic machine as much as they do the Republican machine.” There was a touch of Bernie Sanders in the Hearst message. Trump, for his part, has only this to say: “I’m very, very rich.”

Though he failed to capture the presidency, Hearst actually represented New York in Congress for two terms. It is hard to imagine Trump doing anything so mundane. His ambition is to be the ringmaster of the Greatest Show on Earth, and if it can’t be the presidency (which of course it won’t be), then he’ll be perfectly content to maintain a visual media presence and intermittently steal headlines.

Just like Hearst before him, Trump loves seeing newspaper headlines about himself. He puts his name on city structures, just as Hearst newsreels helped to create a corporate brand that capitalized on one man’s name. Social critics thought Hearst a cheap demagogue and called him a “spoiled brat.” And why not? He boasted that he could produce a war in Cuba. And voilà! Trump brags that he will be a “great” military leader if elected. (Based on what past experience?) Never mind that he hasn’t studied under foreign policy professionals or given thought to lessons of history beyond the most superficial -- just apply what works in the real estate biz. It’s all the same to him: Okay, maybe it’s someone else’s territory, but that doesn’t mean it can’t profit from American aegis, one way or another. Understand another’s culture? Why? Business is business. Diplomacy is business. What isn’t business?

Without indulging in pop psychology, we are all aware of the overall syndrome and its corollaries: Making their own rules, men like Hearst and Trump are not to be told “no” when they see something they want, no matter how small or how grandiose. It extends to the narcissism of personal life: a Hearst or a Trump is not likely to be tied down by one woman. Hearst married a New York showgirl and later took as his mistress Marion Davies, a Hollywood comic actress whose career he subsequently micromanaged. The couple lived together openly for many years, and partied hearty with other beautiful people. Hearst never divorced his wife.

So the personal parallels are more than gratuitous tabloidization. Trump is on his third wife, and he enjoys tiara-studded parades of pretty young things at the Miss Universe and Miss USA beauty pageants that he directs. Trump’s second, and only American-born wife, Marla Maples, was his mistress for some time before they tied a less-than-indissoluble knot. And he got to perform a makeover on the much younger woman: the hair, designer dresses, and all that which could create a desirable public image for a new, improved version of “The Trumps.” Yet, making his own rules, and trading in immigrant wives himself, the Balkanizing husband sees no conflict in his knee-jerk disapproval of Jeb Bush’s “mixed” marriage with a Latina who would drag Bush into the soft-on-Mexican-immigrant camp. The arrogant, insensitive Trump who guarantees that he’ll win the Latino vote is the same guy who, in 2011, said: “I have a great relationship with the blacks.” As though it is possible to extrapolate from a few relationships, select experiences, to an entire race or class of people. That’s hubris. Okay, lunacy.

For those who see Trump as a xenophobe, they miss a curious distinction: He doesn’t hate all immigrants, just the unpalatable ones who come from south of the border. This is the racism of Hearst’s generation: nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Americans saw Mexicans as a mongrel people, lower than “real Americans” on the evolutionary scale. Trump would prefer to dump the poor elsewhere if he could, which explains why he is putting all the blame for the problem on Mexico. Trump’s portrait of America’s decline resurrects the fear of our immigrant nation being flooded with inferior stocks of people. Hearst lived in the heyday of that worldview, when it was said to be America’s destiny to dominate half the globe, and insure Anglo-Saxon control. Trump’s Great Wall is a racial wall, reflecting the isolationist fantasy that Hearst bought into in the 1930s.

Dangerous men with “yooje” egos. Hearst, at least, had the superior satisfaction of knowing that he was once so powerful that he fulfilled his promise to start a war south of the border. Trump’s expectations of negotiating a better deal everywhere are baseless fantasies that prove him the lesser billionaire. All he can really do is entertain us with cartoonish claims about really big ideas. Apparently, that’s enough to obtain popularity among Republican voters (so far, anyway). Said William Randolph Hearst: “The public is even more fond of entertainment than information.” Boy, was he right.

Shares