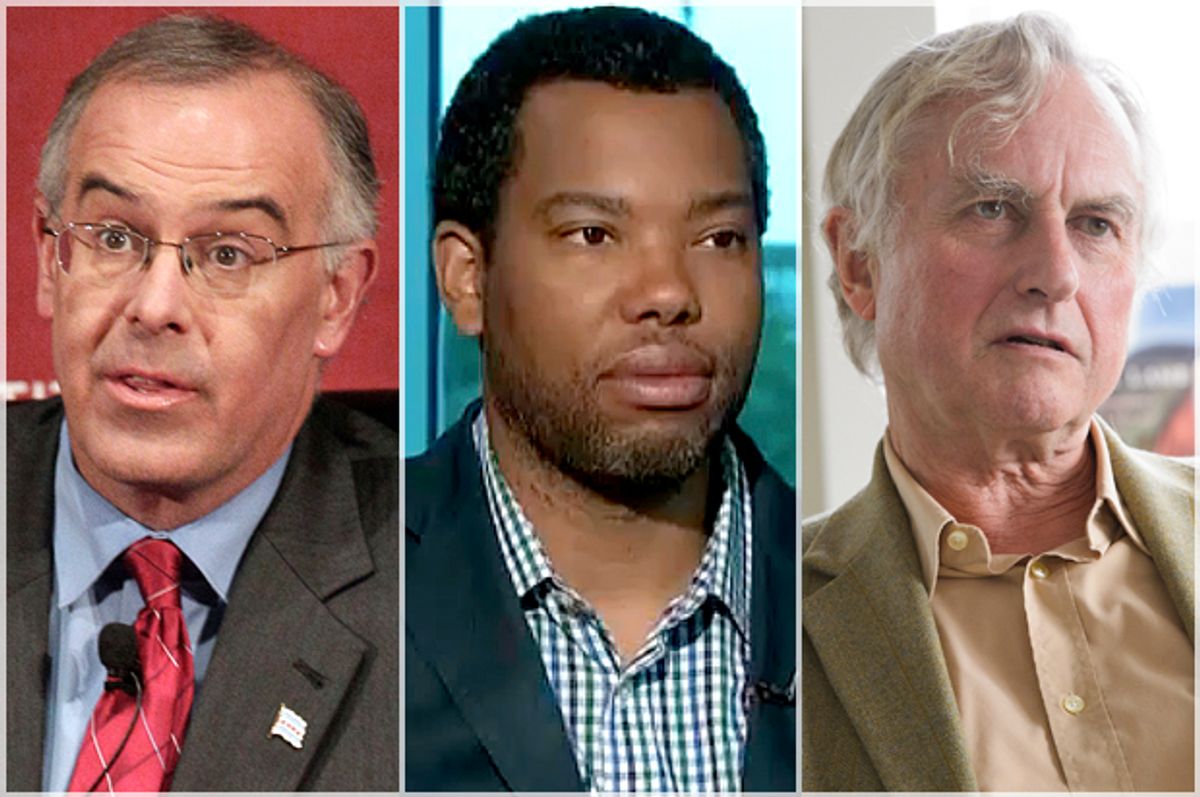

It was somewhere around the middle of the first chapter of Ta-Nehisi Coates' new book, "Between the World and Me," where I began to realize that the quintessential atheist and humanist text of my generation, if there could be such a thing, was neither "The God Delusion" by Richard Dawkins nor "The End of Faith" by Sam Harris, nor any number of other worthy contenders by astrophysicists or cognitive scientists or philosophers or by humanist chaplains like me, but this shit right here.

Coates was writing of good intentions, at the point where I began to recognize. Americans have good intentions. Few of us see ourselves as wanting to oppress anyone. Most of us pride ourselves on not being racist. But in an era where we are trying to do better than simply not kill people like Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin or Eric Garner, Coates writes, good intention "is a hall pass through history, a sleeping pill that ensures the Dream."

I feel compelled, responsible to explain the importance of this book, particularly to a community I call my own. For the past 11 years, I have worked as a chaplain for atheists and agnostics, at Harvard University and beyond. I served for a term as the chair of the advisory board for the national Secular Student Alliance. And I’ve taken part in thousands of conversations about important social changes such as the rise of the “nones”-- the 23% of Americans and 35% of young adult Americans who currently identify as nonreligious, according to Pew.

The point of discussion, in my circles, is often that we must be Rational. We must overcome supernatural beliefs in concepts like God, heaven, reincarnation, "The Secret," alternative medicine (if it was proven, it’d just be called medicine, we like to quip) and many more. And I am in many ways an Orthodox Atheist: I disbelieve in all of the above concepts. Ten years ago I gladly signed a contract committing to never pray in public, not even as a metaphor. My atheist wife, who grew up enjoying religious Jewish rituals like singing the blessings, baruch ata adonai, over Hanukah candles, is often taken aback by the staunchness of my belief in godlessness, even at home, just us, where I will hum along with her beautiful melodies but I will not utter words of praise for a deity. And though Richard Dawkins once correctly pointed out, over lunch, that the difference between himself and me is that I “don’t like to mock religion,” and he relishes doing so, I consider myself to have far more in common with Dawkins, the world’s famous atheist, than not. At least when it comes to metaphysics. Yes, as a humanist I like to consider myself a person of knowledge and consciousness.

But reading Ta-Nehisi Coates woke me up from a groggy state, a kind of semi-lucid haze I did not realize I was in.

Coates, an award-winning journalist for the Atlantic, is primarily seen as a writer on race. And "Between the World and Me" is, on one level, a book about race, with the story of his murdered friend Prince Jones making Sandra Bland’s seemingly similar death look all the more like a depressing and infuriating act of terror. But atheists and humanists tend to see ourselves as transcending culture and race. So much so that I've always been dismayed to find the majority of people who tend to show up at the meetings of organizations with words like atheist and humanist in their names, are so very, very white. Why? Maybe, as I explored in my book "Good Without God" (a title meant to offer a three-word definition of humanism), in an America where religious identity is all many minorities have to fortify them against a society that treats them as inferior and other, identifying as an atheist is far easier for people of privilege.

But Coates' new book is also, boldly, about atheism. It is even more so about humanism. Crafting a powerful narrative about white Americans -- or, as he says, those of us who need to think we are white -- who are living The Dream -- Coates makes a profound statement of what is, and is not, good, with or without god. Coates refers not to Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream, not quite even to the "American Dream,” but rather to The Dream in which we forget our history, our identity and much of our nation's prosperity is built on the foundation of the suffering of people of color in general and black people in particular. The Dream, in other words, is not a state in which only Fox News Watchers find themselves. It is a state that can cancel out the very best of white, liberal, humanist intentions.

If you, like me, are a race-conscious progressive who had never really given serious consideration to the thought that maybe, morally speaking, we actually do still owe reparations to African-Americans: welcome to The Dream. If you, like me, applauded with all your might at the election of our first black president, but had never truly stopped to re-evaluate your life in light of the fact that slavery was the single biggest industry in early American history and thus the “down payment” allowing us all to enjoy lives of relative, super-powerful comfort, welcome to The Dream. Or if you, like me, have walked through predominantly black neighborhoods feeling occasional pangs of fear for your safety, while also wishing fervently that residents of that neighborhood could achieve justice, but if you never fully contemplated the “moral disaster” that because of redlining, profiling and various other unjust policies, laws and scams, each black resident of that neighborhood had to endure fears at least as profound, every waking and sleeping moment, and what an unjust physical impact that might have on them and their families to this day and beyond -- and therefore what an injustice we all suffer, because we are all one human family, right? …

This Dream was made for you and me.

Now you may be asking, what does all this have to do with atheism? Maybe my lack of experience as a reviewer has got the best of me.

Or maybe Coates is not merely a black thinker who happens to be an atheist, but a human thinker of the absolute highest order, who uses both his experience of living in a black body and his atheism to offer some of the freshest insights our culture and society have seen yet.

First of all, the still relatively young author was not only flipping but ripping up the script about church-state separation years before, say, Sam Harris ever considered penning a "Letter to a Christian Nation." Did you ever wonder, in the name of atheism, as to the sociology of why there are so many churches in poor black neighborhoods? Coates did, straight out of Howard.

Sixteen years later, he has become the most deft and creative writer I’ve seen in years in terms of his ability to craft language about the meaning of disbelief. Power, for him, comes not from divinity, but from “a deep knowledge of how fragile everything ... especially The Dream, really is”; a point made more profound coming from a member of the single most religious demographic group in the United States.

Coates even channels the late Carl Sagan, astronomer and humanist ~patron saint, in passages that could inspire anyone, regardless of economic or racial background: “godless though I am, the fact of being human, the fact of possessing the gift of study, and thus being remarkable among all the matter floating through the cosmos, still awes me.”

Is "Between the World and Me" an important but angry book, as the New York Times’ David Brooks suggests, in an epistle that breaks the sound barrier of tone deafness? No, and in fact it angers me that such an interpretation keeps coming up. This is, in the best and most powerful way possible, not an angry book, but a fearful book. “I am afraid,” Coates writes, again and again risking the shame with which fear is too often stigmatized, to share his deeply felt terror for his son, for himself, for all of us.

The most astonishing moment of Coates’ previous book, "The Beautiful Struggle," comes when he explains the mysterious magic of hip-hop music as being, primarily, about fear. And as he says in "Between The World and Me," “fear ruled everything around me”; surely the most realistic and Rational reinterpretation of Wu Tang lyrics I’ve ever encountered. Coates’ unique voice is far more vulnerable than most reviews, even positive ones, give him credit for. Why should we celebrate the vulnerability -- meaning, the willingness to recognize and admit one’s fears -- of a white Christian woman like the famous TED speaker Brene Brown, but fail to recognize the power of that same quality in Ta-Nehisi Coates?

A final concern: Perhaps humanists and atheists will respond negatively to what they will see here as breathless praise. We nonreligious people do not cotton to the idea that anyone or anything is perfect. And neither the present author nor his subject matter is. So I would urge “constant interrogation,” as Coates himself advises in one of the many phrases that echo great skeptic intellectuals like Paul Kurtz or James Randi. But Coates is not unaware of the flaws in his own narrative. He not only owns that the black community and its intellectual tradition isn’t perfect or sacred, he credits his Howard University professors -- the secular imams at The Mecca, as he refers to America’s finest historically black college -- with teaching him this.

Fittingly, the book ends with an expression of profound fear: that the same human motives and frailties that created the institution of slavery have morphed into a technological juggernaut that now threatens every human life, and our very planet, in the form of climate change. Will we, together, come up with a better way to live? Will we do it fast enough to implement those changes and experience a better future together, or will we ironically figure out how to treat one another equally, just as we are floating off vanishing coastlines into oblivion? Maybe, as a humanist, I should be more optimistic. Or maybe I will just admire the amazing little lesson Coates’ mother taught him when he was a small boy, failing or misbehaving at school. She would make him write essays explaining why. Maybe the most humanistic thing we can do right now is wake up from the Dream, at least enough to look at our worst failings -- as humanists, as human beings, as people who may think we are white -- and write, about why.

Shares