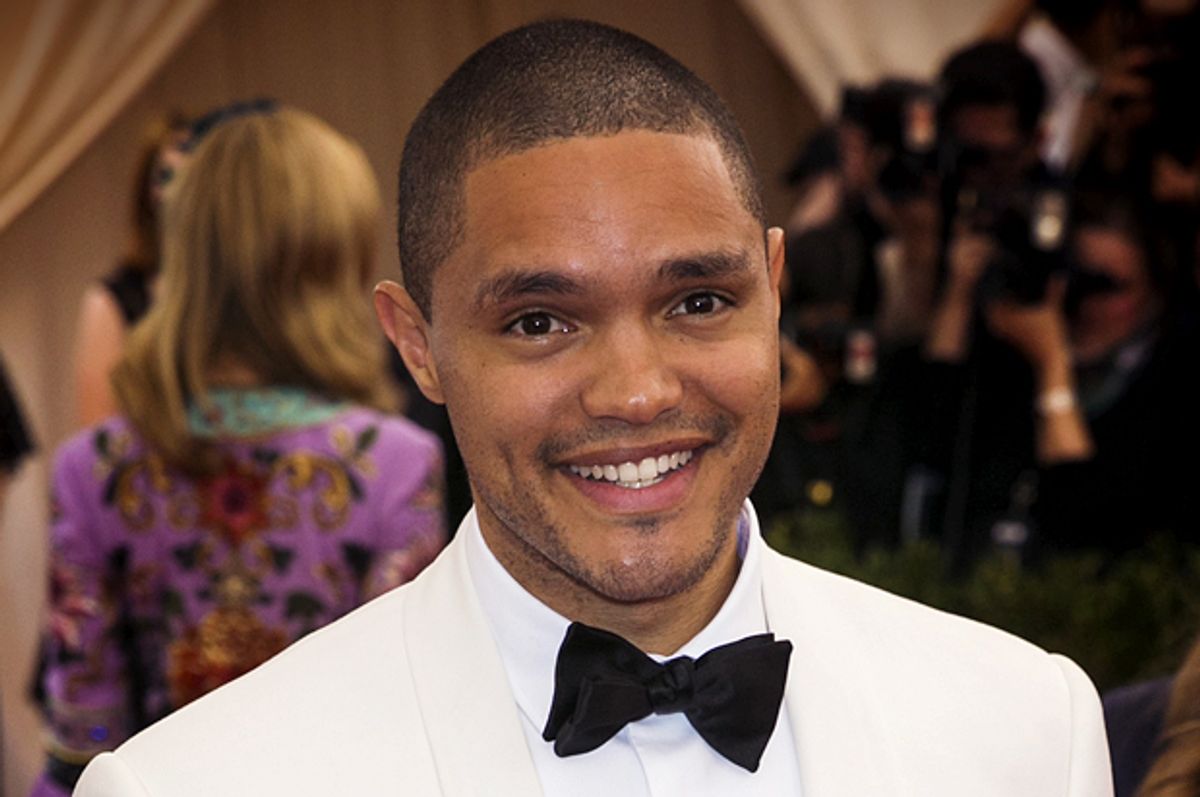

When I asked Trevor Noah what he thought about the fact that his show, along with “The Nightly Show” with Larry Wilmore, would make an hour of black men hosting the news, the 31-year-old South African—surrounded by reporters, fresh off of one of his first stand-up sets as Comedy Central’s heir presumptive to Jon Stewart’s chair on “The Daily Show”—went for a quip: “Well, I think I’m half-white.” The dimpled comedian is quick to smile, even in the face of at least a dozen reporters with recording equipment waving in his face.

It’s an aside that demonstrates how much the comedian is defined by—saturated with, really--the constant and unavoidable issue of race. He performed an hour of stand-up in Santa Monica, California, for his official unveiling by Comedy Central to the Television Critics Association and a small subsection of the adoring public, and from the get-go homed in on race. The first 20 minutes or so focused on police brutality in America, repeating an observation that was less a joke and more, as the bit went on, a refrain, an appeal, a spoken-word lament: “I don’t know how not to die.” He was able to manage the tone of literal murder through mourning, humor and sharp commentary. “You know there’s a chance as a black person you may go to jail. It may be by mistake. It could be the neighborhood you live in, it could be your history with the police. It could just be the fact that those sketch artists make all black people look the same.”

And in order to make everything stick, Noah relies on a tool that Stewart also constantly relies on—self-deprecation. Every comedian has to use it at some point, to ingratiate themselves with the audience. With Noah, it’s even more important than just jokes, though. He’s lecturing on race to an audience that will span the nation and will, through the Internet, go global; in targeting himself, he’s both anticipating the first volley of attacks against him and creating his primary line of defense. Noah’s eager to communicate and reach out to viewers, yes—as he told me, “If you laugh with somebody, then you know you share something.” But my metaphors are martial for a reason; this is a comedic combat zone. Jon Stewart proved the efficacy of comedy as a political tool in his 16 years on “The Daily Show.” Now Noah is wading into the thicket of identity politics, one that has bubbled up in the form of enthusiasm, outrage and commentary around comedians like Amy Schumer, Hannibal Buress, Lena Dunham and more. Except he’s doing so in what has become the seat of the “satirist-in-chief,” around a man who became liberal America’s rallying point. Trevor Noah is facing the gauntlet between impossible expectations and thorny subject matter, and he knows it. What likely makes him the right person for the job is the fact that this unenviable challenge seems to excite him.

Trevor Noah is not Jon Stewart—as he said after the set, “You cannot replace Jon Stewart.” But what they do share, based on his remarks, is an enormous sense of mission—and as I discussed last week about Stewart, an inability, at times, to wholly live up to it. Noah’s now most well-known not for being Stewart’s successor, but for being that suddenly famous newcomer who had made several off-color jokes on Twitter from 2009 to 2012.

Indeed, the Trevor Noah Twitter Controversy, such as it was, is in fact a story at the nexus of a few things “The Daily Show With Trevor Noah” will likely spend a long time taking apart: comedy, race and the online outrage machine. Where Jon Stewart’s target of choice was 24-hour cable news, Noah’s mandate is my own industry: online journalism. “We are in an era of full outrage,” he observed. “We live in the Internet age. Everyone wants clicks. Clicks are what sells. News doesn’t so much anymore. So now you work for what used to be considered a news agency, but now you’re really an advertising platform.” He attributed the blow-up over his years-old remarks to the foibles of online news: “People need clickbait. They need to get you clicking. And it doesn’t help to say, here’s a balanced argument. A balanced headline doesn’t sell. Sell the extreme, go all out, label people, and that’s the best way to get a reaction. Unfortunately, that’s the world we live in now.”

I noted that although Noah was happy to explain the situation and admitted wrongdoing, he rarely, if ever, went so far as to apologize for the remarks. He did not try to justify them, either. In a profile at GQ, he cops to regret and past idiocy; last night, he started a sentence about the dust-up with “What I think is unfair is—" and then cut himself off. These tiny verbal cues might seem trivial, but it appears to be crucial; this is how Trevor Noah refuses to engage with the way the American media typically handles racism. For example, when a reporter asked about his take on Hulk Hogan, he responded:

The thing with Hulk Hogan is—he says he’s racist in the [video]. We can’t judge you and say, “You’re racist”—that would have been a different story. … But he says, “I’m racist!” So now we’re going, “Oh, you’re racist.” … I don’t think Hulk Hogan is a bad person. I don’t think racists, for the most part, are bad people. I think they suffer from something. … I think there’s a better way to handle it. We can’t just—to cut people off, it’s not sustainable. And it doesn’t heal anything. We don’t move forward from that.”

In his stand-up, Noah spent several minutes on the idea of “Racists Anonymous”—a rehab, of sorts, for admitted racists like Hogan and former L.A. Clippers owner Donald Sterling. Racism, he said, is a disease, like alcoholism. But we lack the apparatus or even the willpower, maybe, to treat that disease. And though he mined that idea of racist rehab for laughs, imitating Sterling coming close to falling off the wagon with an ill-considered N-word, that is part of what he wants “The Daily Show With Trevor Noah” to be able to provide. I asked him if rehabilitating racists is a service he hoped to provide.

Yeah, well, hopefully. I think we’ve become too black-and-white with many things in society, whether that’s politics, whether that’s the way we deal with issues. So the Hulk Hogan thing was a great example. I don’t think he’s a bad person. I don’t think he hates black people. But he suffers from racism. And he admitted to that! But now, what do we do? Do we shun him? Or do we try to find a way to rehabilitate the person? … There was a time in the 60s and 70s where, if you looked at Congress, people, they voted across the floor. …Now you’re either this or you’re that. And that’s not how it should be, in my opinion. I think there’s a way we can tackle that.

Is it possible to rehabilitate a racist? Such as, a reporter asked, Donald Trump? Noah responded, “We don’t know, because we haven’t tried. But I genuinely believe it’s possible.”

In our world, this is a controversial stance; we do not have a media apparatus for forgiveness. But Noah’s comfort with the complexity—and his continued poise—strongly indicated to me that he is excited to take on the controversy. As a man from a notoriously racist country, he dubbed himself a “connoisseur” of racism; his outsider’s perspective on American dialogue doesn’t do us any favors. And honestly, nor should it. Noah surprised me, and at times, provoked me; but I was surprised at how thoughtful he was about comedy’s utility in processing the world, and how deliberately he considered the questions about his purpose with the show.

Onstage, Noah demonstrated both his strengths and his weaknesses in the hourlong set that mostly told stories from his short life as an American and the peculiar nature of air travel. At first, both topics seemed a little precious—airports are such a tired canard of comedy. But late in the set, Noah offered a clue to his own fascination with the topic. He’s the first person in his family to have ever flown on a plane, and as a professional comedian, he’s now constantly on the move. And his comedy was not so much about how airline seats don’t recline in the right way or that the food isn’t particularly good—it instead revealed a constant well of curiosity and observation on how people see him, how people see each other, and indeed, how he sees others, too.

And it is a perspective that does not—cannot—ignore race. He implicitly rejects the idea of a colorblind world, and with it, dabbles in humor that bordered on the offensive. His incredible vocal ability allows him to drop in and out of accents with apparently no effort at all; and accents, as we have recently learned, can get you in some trouble. Onstage, a tossed-off concentration camp remark comparing airline security to a prison camp got more groans than laughs, and a section toward the end where he mashed together Mexican Jedi, fake-and-real Arabic, and the healing power of airport security ruffled my own feathers. "I don't strive to be offensive," Noah said. But, he added, "Any joke can be seen as offensive by anyone. Anyone can feel offended by an impression or not." The key, he said to me, is to find "the most honest way of telling a joke."

I am not entirely sold. Noah's jokes about blackness and whiteness are a lot more lived-in and informed than his jokes about any other racial or ethnic experience; and though blackness and whiteness are central to America, they are not all of it. It might be very difficult to stomach a mixed-race man copping an accent that isn't his. And yet at the same time, I am not quite sure if my mixed reaction stemmed from offense or simply from surprise at hearing someone talk so candidly about race. I kept looking for a way his remarks might be inconsiderate—does this perpetuate a stereotype? Does this fall into easy characterization?—and ultimately, I failed to find a simple entry point. It's loaded material, but he's not handling it insensitively, just provocatively.

Which points to what is perhaps the most important takeaway about Noah: He’s willing to let himself be the test subject for this radical new way of talking about race. Comedy Central is clearly banking on race relations as being an increasingly important topic in the news; with Noah, they have an anchor who is willing to make himself be the guinea pig, the target and the crusader for change, all at the same time. If his politics didn’t line up with Stewart’s, he said, “I don’t think Jon would have picked me to do the show.” This is Trevor Noah’s “Daily Show”: Past controversies do not define the present, and change for everyone is possible. “Even Barack Obama was against gay marriage,” he pointed out. “And just a month ago, the White House was in rainbow colors.”

Shares