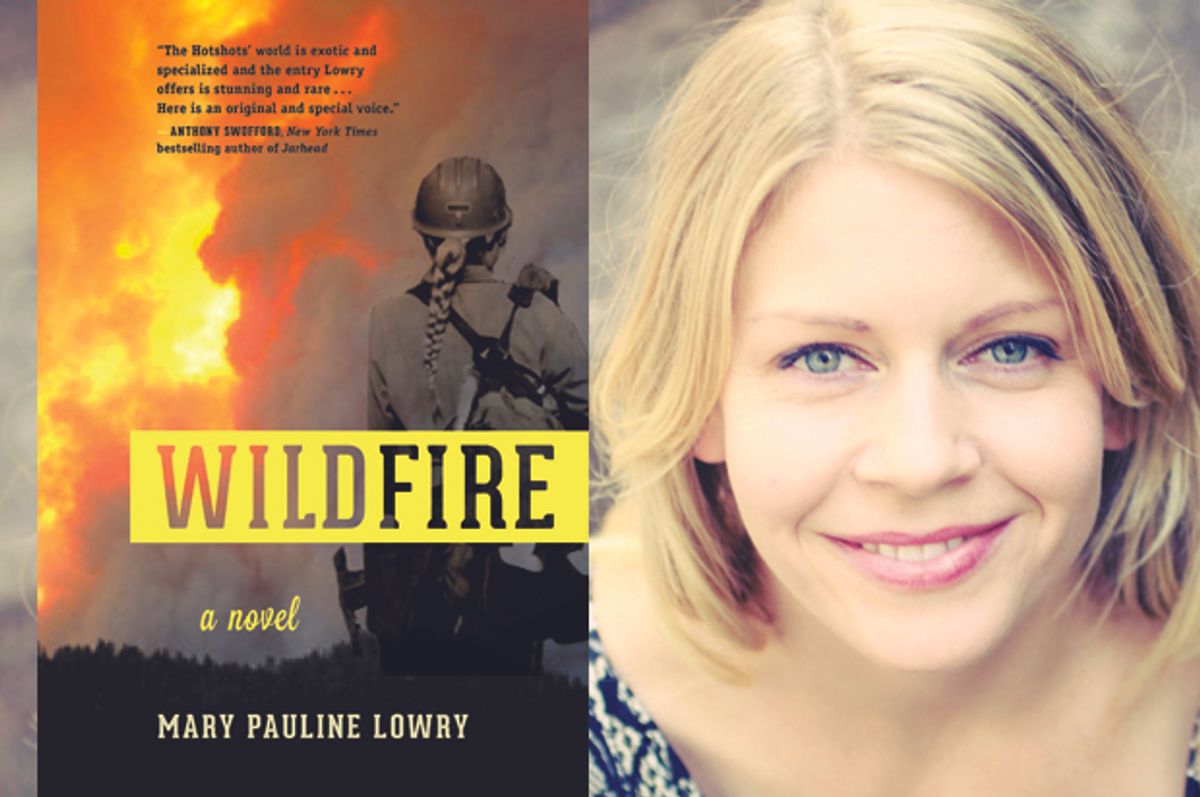

Mary Pauline Lowry’s powerful first novel, "Wildfire," about a wildfire crew, is out from Skyhorse Publishing. I had the pleasure of sitting down with her in my dining room a few weeks ago. She brought my daughter a watering can. We drank Santa Monica tap water and talked about her startling debut, some books she loves and a mentor we both share.

In your novel, “Wildfire,” you write beautifully about nature—we smell and see it. And there is a sense that it is a dangerous place. Did you know you were doing that when you started writing the scenes that are out in nature?

I don’t know if it was intentional. But I did work for two years as a wildland firefighter and during that work I was hyper-aware that nature is essentially very dangerous. When I was out there on the fireline, I knew that nature could kill me in multiple ways at any moment. So I’m glad that sense came through in the book.

Is Julie a whole cloth fictional fabrication or is she parts of people you knew, people you served with, and your own self?

Julie is inspired by my own experience. Like me, she is from Texas and went to Colorado College. But she is more fearless, more reckless, braver and more self-destructive than I am. I grew up loving adventure stories and wanting to see more women having kick-ass adventures.

“Wildfire” is a pretty kick-ass adventure. In the novel there is this great game, the dictionary game. Who is that? Hawg?

Hawg is the character who is great at the dictionary game.

It first happens at about page 31, and by now many readers would feel a little bit like, “OK, these are some sexist and moronic bastards. They are calling her ‘splittail.’” It feels a little dangerous for a while. And then suddenly these guys are playing this dictionary game. Did you time that purposefully?

The dictionary game is something that guys on my crew played all the time. One guy I fought fire with just had an amazing vocabulary, so the rest of us would throw out words for him from the dictionary to see if he could define them. Another guy on my crew always kept a copy of “The Sun Also Rises” in the cargo pocket of his Nomex fire pants. Many of the guys on my crew were very intellectual, very well-educated. But there was an interesting contradiction that some were also overtly sexist, vulgar and wild. And so I wanted to show both sides of that.

There’s a great line, “It’s a lifetime of fighting fires, drinking beer and eating red meat.” That’s how you describe one character. And I thought, “Oh my God. I love that guy.” That’s who these guys are, right?

Pretty much.

OK. Let’s talk about sex.

OK. Let’s ….

You use fire as a metaphor for sex, and for love, and for grief in remarkable ways. Is this because you knew the language of fire, knew the cost of fire, or was that something you had to work hard to craft?

That was something that came without much effort. When you fight fire, you are so steeped in fire that it does become a metaphor for everything.

A few great fire lines, “My heart flying apart ...” “I felt like a tree torching out …” That’s during sex. It’s great stuff. “Scrogging like a crazed weasel.” I like that one, too.

Yeah, that was my hotshot buddy Luke’s phrase, actually. He would always talk about people “scrogging like crazed weasels.” And I think it’s very descriptive, especially when you are thinking about two people having sex where the idea sort of repulses you, you know? Because weasels can be really gross.

Let’s not talk about it.

There is a claustrophobia to the book, to Julie’s psyche. She lost her parents as a young girl, at 12. She was into danger right away, which is a natural psychological response. She is bulimic when we meet her. And early on, I think maybe during one of the first fires, she says, “There was nowhere for me to go.” Talk about what that means as a woman in the middle of a forest fire.

The idea of claustrophobia does in some ways really describe the experience of being on a hotshot crew, because even though you are out under big skies, you have no autonomy. In many ways it is like being in the military. You make the decision to join that hotshot crew, and once you are on it, you don’t get to make another decision about when or where you eat, sleep, take a shit, take a day off, anything.

But for Julie is there some kind of safety in that claustrophobia, too?

Yeah. Julie really wants a place of belonging. And when you are on a hotshot crew, if you can be accepted by your crew mates, you have this incredible place of belonging.

Is there a beautiful simplicity to it?

Yeah! You know who you are. You know where you are. You don’t have to worry about paying any bills. And if a hotshot crew stops at a gas station and goes in to get something to eat, people look at them as if they are one entity. There is an anonymity to it that is very comforting.

The group would look like a tight team. And the outside observer would never know who the leader is, or the pecking order. But there is a specialized language and understanding among the team.

Years ago, I had a boyfriend who was in the Marine Reserves and when I would drop him off for his training weekend he would be wearing his camis, and he would get out of the car and step into his unit and I would lose him in the crowd. And he would say, “Oh, I could look at any of those guys and if I saw only the corner of one of their ears I would know exactly who it is.” And that’s how it is on a hotshot crew. You get to know the people so well that there is this individuality that you see. But from the outside it’s a group in which everyone looks almost identical.

I won’t give away your powerful ending on the mountain. But much of your book, and especially the ending, reminded me of those last few pages of “A River Runs Through It.” I weep every time, and I wept finishing your book.

“A River Runs Through It and Other Stories” by Norman Maclean is one of my all-time favorite books. The epigraph to “Wildfire” is from a short story in “A River Runs Through It and Other Stories.”

I didn’t even notice that. I’m such a dope.

You have a copy of the galley of “Wildfire,” and the epigraph is only in the final hard cover. So you are not a dope.

Norman Maclean started his career working for the Forest Service and fighting fires. He fought the Great Fire of 1919 in Montana. So he has always been a hero to me, both as a forester and a man of letters, and I’m honored anything about my book reminds you of “A River Runs Through It.”

Are there any first responder books that you like that get it right?

I love “Jumping Fire,” which is a memoir by Murry Taylor, who is another one of my all-time heroes. When he retired from smokejumping at the age of 56 he was the oldest smokejumper in the history of wildland firefighting. That is a fantastic book about the world of wildland fire that I highly recommend.

We share the great mentor, Joy Williams. I studied with her in Iowa, and you studied with her in Austin a couple of years later. What did Joy teach you about writing?

Joy taught me to be comfortable with the way that I write, which she said was “very visceral.” I don’t plot things beforehand. I just kind of go with the story as it unfolds. And she told me that is the way she writes. And that gave me confidence to continue on that path.

And Joy Williams modeled for me what it was like to be a writer. She was a real writer in the flesh, and so talented. To me, writers were like rock stars. They were not like real people that you could meet or be. So just to see her doing her thing was incredible.

And also, Joy’s confidence in my work was so helpful. She pulled me aside and said that she had only ever helped one student before, a student named Tony Swofford and that he had written this book called “Jarhead,” and that it was going to be coming out, and it was very good. And then when your memoir “Jarhead” came out, and it was real, and it was a fantastic, haunting book, that gave me some sort of sense that maybe I could do this, too.

So Joy modeled the writing life for me, but she also just said that my work was good, and that meant everything to me.

That’s high praise from Joy, right? She’s an amazing lady. She is a brilliant writer, also.

Yes! I recently read her newest book, “99 Stories of God.” And the way she writes as a woman of faith who is questioning the suffering of animals and humanity is amazing.

Joy reminds me of Flannery O’Connor in her ability to balance faith in a higher power with a fascination with human evil and darkness and suffering.

You do that, too. Nature becomes the evil thing. The team suffers a lot. But there is the beautiful stuff at the end when Julie finally knows she belongs.

And I think the nature in this book may be like the God that Joy Williams writes of in that it is beautiful, it is bountiful, it is merciless.

Shares