In 2006, Tom Stoppard (our greatest living playwright if you haven’t heard) gave us "Rock ‘n’ Roll," a tale of personal conflict set amidst a political revolution. The play opens in late-'60s London as a piper (Pink Floyd’s Syd Barret) serenades a young girl from atop a garden wall. It ends in 1990 with the Stones playing Prague. Along the way, "Rock 'n' Roll" traces Czechoslovakia’s long road from Alexander Dubcek’s Prague Spring to Vaclav Havel’s Velvet Revolution. As Stoppard tells it, musicians -- Dylan, the Stones, the Plastic People, the Velvet Underground --led the way; that rock-and-roll is apt to foster freedom because it is rebellious even when it isn’t political. He says it often works this way: artists leading politicians to democracy.

On Thursday, Jon Stewart, perhaps our greatest political satirist, bids us farewell, for now at least. No matter when he chose to go, it was bound to feel like the worst possible time. Stewart has spent 16 years pleading for a rebirth of democracy in America. Our national circumstances are, in a way not disimilar from those of the Czechs a generation ago: our culture more democratic than our democracy; our politicians silenced not by a communist dictatorship but by their own corruption. So we too look to our artists for political leadership.

In the mid-20th century, America was full of artists telling hard truths: Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Nina Simone, Marvin Gaye -- a list that did justice to the era would fill pages. We had braver political leaders then too, and of many different sorts: Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, Gloria Steinem, Ralph Nader. Times, of course, have changed. In the early days of this century it often felt as if Jon Stewart and Bruce Springsteen were the only people telling the truth about anything. We may now be entering a season of renewal, but its buds are still tender and few, and need new artists to water them.

Stewart’s artistry is rare and while it has many antecedents, surprisingly few are recent or local. In America, the media age spawned few political satirists. Radio helped the gentle populist Will Rogers become a megastar, but Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl trafficked in political satire and got more or less run out of town for it. (Bruce more, Sahl less.) Our biggest comics have been mostly apolitical: Mel Brooks, Woody Allen, Steve Martin, Eddie Murphy, Robin Williams. But like rock and roll, comedy needn’t be political to be subversive. Seeing Chaplin or Lily Tomlin or Richard Pryor, we’re reminded that social consciousness and political consciousness are pretty much the same thing. "Duck Soup" was the Marx Brothers’ most political film, and maybe their best, but no matter the film, whenever Harpo squeezed a clown horn, somebody, somewhere, questioned authority.

In 1962, the first fake-news show aired in the UK to critical and popular acclaim. "That Was the Week That Was" employed such comic geniuses as Roald Dahl, John Cleese, Graham Chapman and Kenneth Tynan. It was going strong in 1964 when the BBC, fearing controversy in upcoming elections, pulled the plug. An American version was also loaded with talent: Buck Henry, Tom Lehrer, Calvin Trillin, Alan Alda; guest shots from the likes of Mike Nichols, Elaine May and Woody Allen. It lasted 18 months. In 1967, "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour" gave us the most frankly progressive political humor TV had ever seen. Twenty-eight months later, CBS execs, enraged by constant, public run-ins over censorship, gave it the ax.

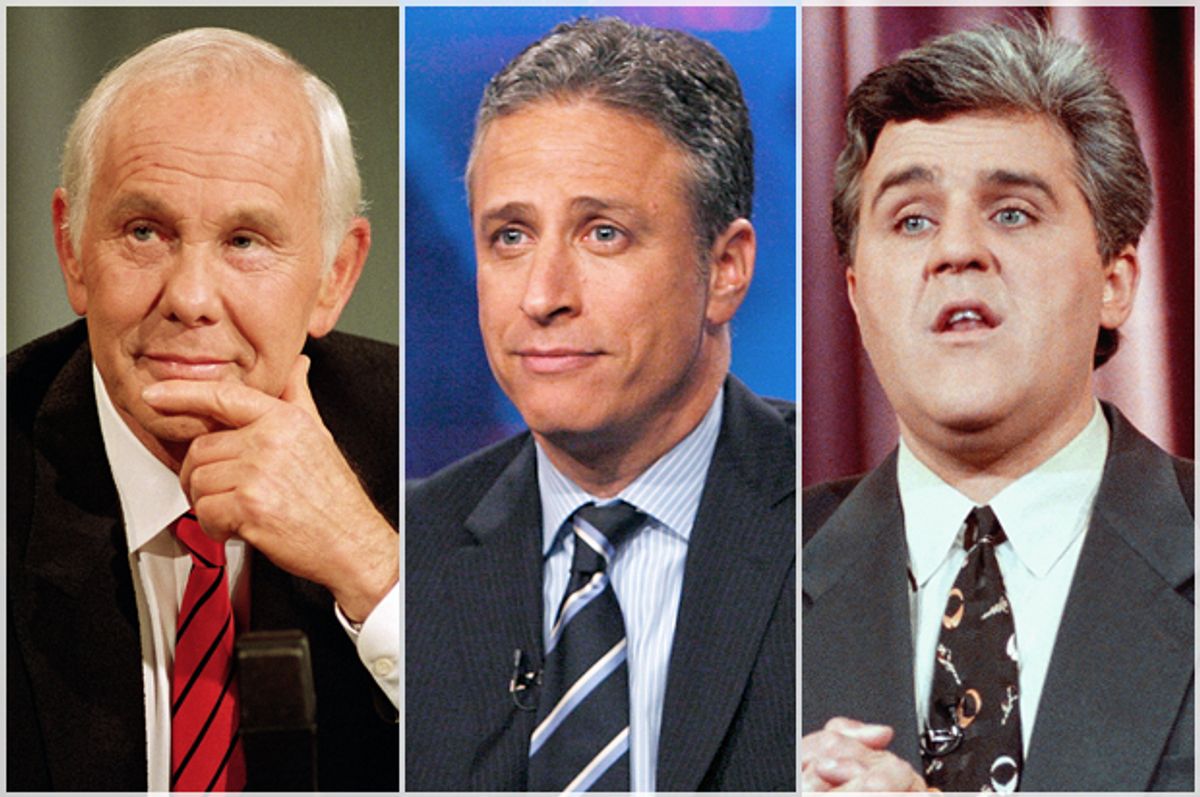

After that, most TV political humor was of the Bob Hope school -- trite riffs on trivial personal flaws, calculated to offend no one, not even their alleged targets. Late-night hosts from Johnny Carson to Jimmy Kimmel have subsequently cut closer to the bone, but still played by Hope’s rules: Never get ahead of your audience. Never let them see your point of view. Never say anything real or important.

There were two exceptions: In a five-year run starting in 1969, Dick Cavett engaged the big issues of his turbulent times, especially Vietnam and Watergate; and, in his amazing 33-year late-night career, the naturally reticent David Letterman grew able to discuss the most difficult personal and political issues with rare candor and feeling. But in monologues, even these pioneers mostly played by Hope’s rules. Who wouldn’t? The name of the game is get a laugh, and everybody wants to end up like Johnny Carson, not Lenny Bruce.

In 1975, NBC handed an 11:30 p.m. Saturday night slot it wasn’t using to a unknown 30-year-old Canadian named Lorne Michaels. "Saturday Night Live" has lasted 40 years, seven more than Letterman, though they needed a few hundred hosts to do it. Its political humor has given us some great laughs, but it too plays by Hope’s rules. Its first political impression was Chevy Chase’s Gerald Ford, and was about Ford’s clumsiness, not the Nixon pardon. Twenty five years later, Will Ferrell’s George W. Bush was a moron, not a warmonger. Tina Fey’s Sarah Palin, sculpted from the marble of Palin’s own words, revealed her ignorance, not the viciousness of her politics or character. Such were television’s rules -- rarely broken, still firmly in place and looking like they’d last forever. And then along came Jon Stewart.

Little in TV history said there could be such a thing as "The Daily Show." Nor was there much in Stewart’s history to suggest he’d be the one to make it happen. Prior to his taking it over, "The Daily Show" was a sort of cross between "Weekend Update" and "America’s Funniest Home Videos." When its host, Craig Kilborn, took off, its producers’ picked Stewart in hopes he’d give it a topical edge. Stewart is a smarter, edgier sort than Kilborn, but little in his resume indicated he’d try to put Comedy Central at the center of American politics, or that he could do so even if he wanted to.

Before he got the "Daily Show," Stewart hosted a rafter of other programs, among them Comedy Central’s "Short Attention Span Theater," which featured clips from movies and standup routines, MTV’s "You Wrote It You Watch It," in which the cast acted out scripts sent in by audience members, and something called "Where’s Elvis This Week?," a BBC coproduction that, to its credit, actually had some discussion of real issues, even if nobody now remembers it.

When Stewart got "The Daily Show" he didn’t inject it with all new DNA. Stephen Colbert and Lewis Black were already there. The producers knew the general direction they wished to head in. But if they knew which way they were going, they had no idea how far. Stewart wasn’t like Craig Kilborn, but he wasn’t so different either. One senses the show changed him as much as he changed it; that as time went on, his vision broadened, his concerns deepened. If so, he joins Letterman in an exclusive club -- the rare few who became better people as a result of being on television.

Stewart was soon driving "The Daily Show." He, more than anyone, made it what it is today. To understand what that is, one must understand two things:

One is the comedic tradition from which he springs. When asked about influences, Stewart inevitably cites contemporary or recent American comedians. That may be the all of it, but it’s hard to go from poking fun at a president’s golf swing to questioning the moral premises of American foreign policy without tapping some deeper vein. It won’t do to compare him to history’s great political satirists -- too many will bridle at the thought of it -- but it is essential to see that he follows in their line. So much of our greatest comedy is the work of writers who felt in their souls the absurd injustice not only of society but of life itself and railed against it.

So much of comedy is a lamentation. It is why Jonathan Swift chose for his epitaph the words, “Where savage indignation can lacerate his heart no more.” It is what drives Swift and Voltaire -- in "A Modest Proposal" and "Candide", respectively -- to impute cannibalism to modern humankind, and why in the greatest of modern comic novels, Joseph Heller's "Catch 22," the tone darkens with each chapter until the protagonist, Yossarian, sees that his own cynical indifference has killed a beloved friend. He can no longer take refuge in its repose, but must finally act. At last, Heller says, he knew the meaning of "Catch 22":

That every victim was a culprit and every culprit was a victim and that somebody had to stand up sometime and try to break the lousy chain of inherited habit that was imperiling them all...

After 9/11 and again after the terrorist massacre in Charleston, some asked how Stewart, a mere comedian, could express so well our deepest feelings of numbness and grief; of strength, perseverance and love. There is no mystery. Our greatest comic writers have done just that for centuries. It may well be that a Yossarian-like epiphany informed the maturation of Stewart’s vision and even his need for new outlets to express it. What is certain is that many of the same passions that now drive his comedy informed those statements.

The second thing one must grasp is Stewart’s politics, or what he discloses of it. No ideological abstraction, it is rooted in foundational values of honesty, civility and reason. Two of his most famous moments have come not in his studio but in visits to CNN and the Washington Mall. At CNN, his anger at our degraded politics boiled over into a rant at "Crossfire" cohosts Tucker Carlson and Paul Begala, whom he told to “stop hurting America.” On that day, Stewart's grief at seeing our public discourse devolve into partisan performance art was palpable. For a brief moment, he made us see the price we pay for turning our democracy into one more vulgar entertainment.

In 2011, at the National Mall, Stewart and Colbert drew over 200,000 people to "The Rally to Restore Sanity." (Doubtless the inspiration for the event struck when the ever-fascinating Glenn Beck chose the anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington to reserve the same spot for a right-wing rally.) Addressing the crowd, Stewart urged less vitriol, less fear-mongering, and a renewed commitment to reasoned compromise. “We live in hard times not end times, not end times…most Americans don’t live their lives solely as Democrats or Republicans, liberals or conservatives.” Later he’d tell Rachel Maddow that he didn’t mean to posit a false equivalency between left and right; only to convey his view, widely shared by the American people, that “the conflict is actually corruption versus not-corruption."

Stewart admits to leaning Democratic, but has called himself an independent and even a socialist. Still, in 1988 he voted for George H.W. Bush, because he was convinced of his basic decency. I doubt Stewart has many Bush votes left in him, but that vote speaks to who he is, or would be: Oliver Wendell Holmes’ "reasonable man," a person who is honest with himself and others, who reflects the values and standards of his community, who makes decisions based on those values and standards and, to the best of his ability, on logic and evidence.

Holmes famously helped found the philosophical school called American Pragmatism. "Capital P" Pragmatists, like most other pragmatists, abhor ideology and believe we know the truth by its consequences; that is, by its practical utility. Pragmatists don't think truth is absolute or even ascertainable, but that rigorous logic can arrive at a reasonable and provisional facsimile that remains true until the world proves it false. Some say Barack Obama’s cool rationality, contempt for ideology and fondness for compromise mark him as a Pragmatist. Noted intellectual historian and Harvard professor James Kloppenberg, a big Obama fan apparently, wrote a book about it in which he concludes that it’s mostly true. Kloppenberg has a superb grasp of Pragmatism, but less of a handle on politics and no clue at all as to who Obama is.

Holmes popularized another big concept: The "marketplace of ideas." It means the free exchange of ideas and information under rules fostering transparency, civility and reason. The marketplace of ideas is not a private auction. It can’t bear secrecy, corruption or evasion. Absent a marketplace of ideas, Pragmatism cannot elevate politics or improve policy. Obama’s civility is a welcome relief from Republicans spewing toxic sludge all over cable TV. But a man who sells off the public option in a secret meeting isn’t operating in a marketplace of ideas -- is thinking of politics, not philosophy.

I don’t know if Stewart knows or cares about American Pragmatism, but for almost 17 years his show has been a monument to it. Someone should write a book about that. With the media mesmerized by gossip and horse-race politics, he met our need not just to expose hypocrisy but to understand the issues it obscures. That we turn to a comedian for logic and leadership is really no surprise. It’s just culture saving politics; Voltaire’s smile of reason in our own Velvet Revolution.

It’s been painful seeing first Colbert, then Letterman, and now Stewart fold up his tent and move on. I’ll miss all the late-night laughs, but with Stewart’s departure the institution with the biggest hole to fill isn’t Comedy Central, it’s the Democratic Party. Stewart took a form of satire that TV had never tolerated and made it thrive. He turned a feeble comedy show into the most honored program on air, with 18 Emmy and 2 Peabody awards. He nurtured a stable of brilliant comics, including three -- Colbert, John Oliver and Larry Wilmore -- who not only extended his brand but expanded his vision. Most amazingly, he used a half hour on late night basic cable to challenge how we report politics and debate policy. By honest, reasoned, respectful debate he became America’s most indispensable progressive.

In coming days we’ll be reminded of just how big a role Stewart plays. Two hours after Stewart tapes his final show the crazy Republicans will hold their first debate of the post Stewart era. We wait with bated breath to see who if anyone holds them to account. The Democrats have other faults. The Iran nuclear deal and the tragic death of Sandra Bland are but the latest reminders of how they duck debates and, once caught up in one, how clueless they can be. For 17 years Jon Stewart taught them how to make a case. We can only hope someone took notes, wish Stewart well, and pray for his speedy return to the public spotlight.

Shares