State of Mind

The state of the mind gets oppressed.

The longer it takes, the quicker you

Break. Choose to let the wind blow.

The foretelling of time spelled unknown.

I still don’t know why continuously I

Feel alone. The bare feet have nowhere

To go. And I’ve lost my way home.

Count from one to ten to please my

Soul yet inside remains a big hole.

When I’m in the most or the warmest

I still feel the brush of the cold, the

Urge to have someone to call,

For I’m the one who didn’t have it all. —Annasuena

Some days, Annasuena simply longed to be a girl. She couldn’t say what her ideal girlhood looked like, and she did not need ideal anyway. If she could re-create her past, she would locate herself in a time before she knew the troubles that now consumed her.

She would reconstruct her family life. Her mother would be alive and Annasuena would grow up living with her, and with her brothers and sister. They would all stay together in the same home. She didn’t have to live with her father, but she would know who he was. She would have the chance to meet him, to know what he looked like, to see whether she inherited her deeper complexion from him.

Cape Town or Johannesburg—she didn’t care which city the family lived in. They didn’t have to be rich and their house need not be large. For all she cared, it could be a concrete, three-room, government-issued house in a township. But something more than a shack, more than plywood walls and plastic tarps, the roof a corrugated iron sheet held down by old tires and heavy rocks to keep the winds from whipping it away. At night, instead of lying awake listening to the rats crawling under her bed, she would snuggle down with her little sister under a soft pink blanket that smelled flowery, like frangipani, from her mother’s perfume when she leaned down to kiss her girls goodnight. After her sister had fallen asleep, Annasuena might keep a light on late into the night as she wrote poems in a diary.

As she grew older, her elder brothers would turn protective and look out for her. None of her other male relatives would so much as leer in her direction.

She did not have to attend private schools, but she would attend school, every year, uninterrupted. She would study hard and earn good marks, except maybe in mathematics, which she would never understand. She would sing in the choir. Before she knew it, she would be entering Grade 12, her Matric year. For learners in South Africa, high school culminates in Matriculation exams. Their exam results determine whether they earn a high school diploma, and whether they qualify to attend university. Most students of her generation do not stay in school long enough to take Matric, or do not pass their exams. But Annasuena knew that if she made it as far as Matric, she would certainly pass.

To celebrate her accomplishment, if she and Phelo were still together, she would allow him to escort her to her school’s Matric Dance. She would wear a long satin dress, in purple. It would drag along the ground even if she wore her highest heels. Her hair would be in long, thin auburn plaits, and she would wear crystal earrings that dangled nearly to her shoulders. This might be the first night she would sleep with Phelo, though honestly, they probably would not have waited this long. But it would be her choice. And if they had sex, they would be careful.

She would be HIV negative, and she would stay that way.

Truth be told, whatever advantages Annasuena had inherited as she began life remained unrealized. As a young South African, she was one of the “Born Frees.” Finally, her country now granted freedom to everyone with her skin color. But freedom implies choice. Annasuena had already seen her life, her future, even her own body altered by choices made by other people. What could freedom mean for her? What had it meant to be born to a mother who was a famous singer, when what a girl needed was a mother?

If she could have had the girlhood she dreamed up, Annasuena thought she might have had a very nice life. But she had this life. Orphaned at ten, looking out for herself. Growing up from place to place, with family or family friends. House to shack, township to township. Struggling to finish Grade 9. HIV positive and terrified of falling ill. Eighteen years old.

I met Annasuena soon after I arrived in South Africa in January of 2010. I was to live there for a year as a Fulbright Scholar and lead a creative writing club for teenage girls at J. L. Zwane Presbyterian Church and Community Center in Gugulethu, a black township about ten miles outside Cape Town. She became one of the first members of the club, which we named Amazw’Entombi. In Xhosa, it means “Voices of the Girls.”

Annasuena and all the other girls who joined Amazw’ Entombi were part of the Born Frees, the first generation of black South Africans born after apartheid and coming of age in a newly democratic nation, following the 1994 elections that made Nelson Mandela South Africa’s first black president. Apartheid, an Afrikaans word with Dutch origins, means, literally, “separateness, or a state of being apart.” For nearly fifty years, it was the government-approved and enforced law of racial segregation throughout South Africa. Apartheid classified and ranked people according to their skin color and one of four assigned racial categories.

Whites were people of European origin, predominantly Dutch and British. Whites make up 8.9 percent of the country’s population today. Below whites on the racial ladder came Indian South Africans, people of Indian descent, only 2.5 percent of the population and primarily centered in the city of Durban. Then, so-called “coloured” people, those of mixed race, a melting pot of European, Bantu, Asian, Khoikhoi, and San blood, and a term some people find offensive. “Coloureds” make up the majority of the population in Western Cape and Northern Cape Provinces, including Cape Town, although this group only comprises just under 9 percent of the population nationwide.

Finally, on the bottom rung, were blacks, known then as Bantus, natives, Africans. The vast majority of South Africa’s population—almost 80 percent—is black.

Under apartheid, blacks and “coloureds” could not vote. Under apartheid, your race determined everything. Where you lived, traveled, went to school, if at all, and what you could study. Where you worked and what kind of work you did. Whom you could marry. Where you worshipped God. What toilets you used, what beaches or parks you visited. What benches you sat on as you waited for a taxi, and which taxi you could take. In which graveyards you could bury your dead.

After the end of apartheid, these restrictions were lifted. But now, along with freedom, the Born Frees were inheriting a country awash in contradiction. Democratic South Africa has one of the most progressive constitutions in the world. Discrimination is prohibited—whether based on race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, color, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language, or birth. The constitution set up the Commission on Gender Equality on behalf of women and girls, one of six state institutions intended to promote democracy and a culture of human rights in the republic.

South Africa also has one of the world’s highest levels of violence against women, second only to the war-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo, and has been called the rape capital of the world. More than a third of girls have experienced sexual violence before the age of eighteen. Levels of child rape, including that of infants, are likely underreported. The country has the world’s highest number of people infected with HIV, an estimated 5.6 million. Young women are particularly at risk. Of South Africans aged fifteen to twenty-four who are infected with HIV, three-quarters are women.

The Rainbow Nation has the third-highest level of income inequality in the world, a yawning gap between rich and poor, greater now than during apartheid. A quarter of South Africans live on less than $1.25 a day; 85 percent of whites are relatively wealthy, 85 percent of blacks, relatively poor. Some call it economic apartheid. Since the educational system also remains steeply inequitable, the young are becoming increasingly unemployable and unable to escape generational cycles of poverty. One report estimated that seven out of ten of the Born Frees who have reached age eighteen did not remain in school through Grade 12 or did not pass the Matriculation exams.

These were facts I learned about South Africa as I prepared to live there. I saw the implications of all those statistics as I got to know some of the Born Frees through Amazw’Entombi. The lives of these girls embodied the complicated and brutal history of their country, its present struggles, and all the promise it yet holds. Numbers receded; names took their place.

Girls like Ntombizanele, whose name means “No more girls.” Like Annasuena, she lost her mother at too early an age. She wanted to earn her Matric by retaking the exams she had already failed once, but untreated depression threatened to overcome her. For Sharon, her dreams were not hers alone. She carried the weight of her family’s expectations: to succeed and provide for them materially, to earn an income that could help to build an additional room onto their overcrowded house or buy a car. Orphaned by AIDS and HIV positive herself, Olwethu sometimes appeared resigned to her fate. Worse, she seemed to tempt it, skipping out on school and finding an older boyfriend who turned abusive. As Olwethu floundered, her younger sister, Sive, excelled at a boarding school for orphans forty miles from Gugulethu. Olwethu had trouble articulating what she wanted for her life, even more difficulty in recognizing her own worth.

Then there was Annasuena, the girl I came to know best of all. Brimming with moxie and excuses, her expectations for her life changed from day to day. She knew well her strengths and occasionally recognized her faults. She saw most clearly where other people had failed her, and she learned she could depend on no one but herself, and sometimes not even that.

The Born Frees and democratic South Africa entered adolescence together, and the growing pains have been ragged and sharp. For all these girls, adulthood muscled its way into their lives years before any birthday declared them of age. While their fellow South Africans attempted to characterize their generation, these burgeoning young writers discovered that they held a particular power in their own hands—the ability to define themselves with a pencil, a notebook, and a circle of listeners.

They all had their own big stack of cake.

Two slices and a cup of Coke was all

I had to take and in my own sense

Of quiet, pain thunders upon the content

Of conscience releasing moments of my sub-

Conscious and the claims that declare

Me obnoxious.

You could only see me in the settings

Of the sun, webbed in dark places

That hide me. I long not to be noticed.

But know that I still exist, that I

Am human in my own being. —Annasuena

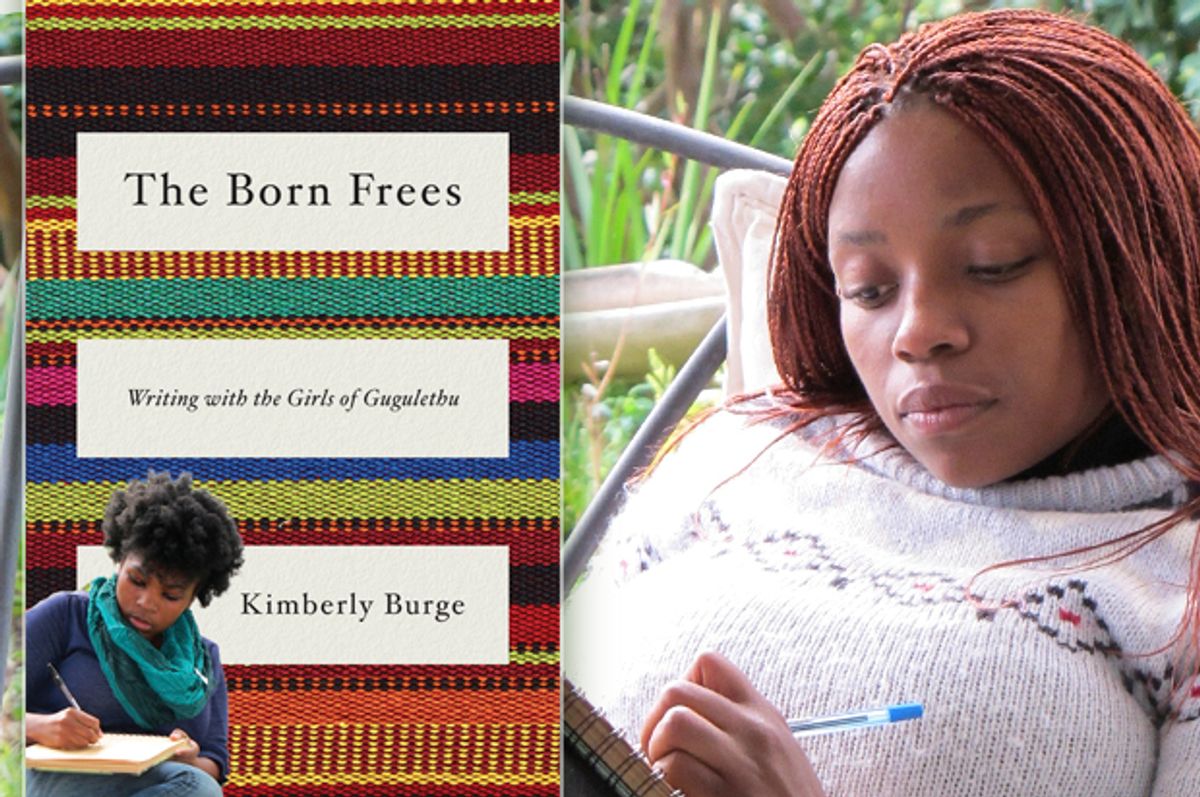

Excerpted from “The Born Frees: Writing With the Girls of Gugulethu” by Kimberly Burge. Published by W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright 2015 by Kimberly Burge. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares