“Call Me Lucky” is director Bobcat Goldthwait’s affectionate—and highly affecting—portrait of curmudgeonly comedian/activist Barry Crimmins. This documentary is, like most of Goldthwait’s work, funny and disturbing. After comedians like Patton Oswalt, David Cross and Kevin Meaney talk about Crimmins’ talent for being a rude, funny, obnoxious truth-teller, there is a revelation that puts the comedian’s story in a whole different perspective. Suddenly, “Call Me Lucky” becomes a story about speaking openly and honestly to helping others overcome trauma and allow for coping and healing.

Goldthwait’s film is a mature and heartfelt entry in his career that began with his manic antics as an actor in “Police Academy” movies. (He now says those films “make me want to jump off a bridge.”) They eventually begat him directing dark comedies like “Shakes the Clown,” “Sleeping Dogs Lie” and “World’s Greatest Dad,” which addressed the respective issues of alcoholism, bestiality and autoerotic asphyxiation. Goldthwait continues to mine taboo subjects in “Call Me Lucky,” and the film shows how comedy and pain interlock.

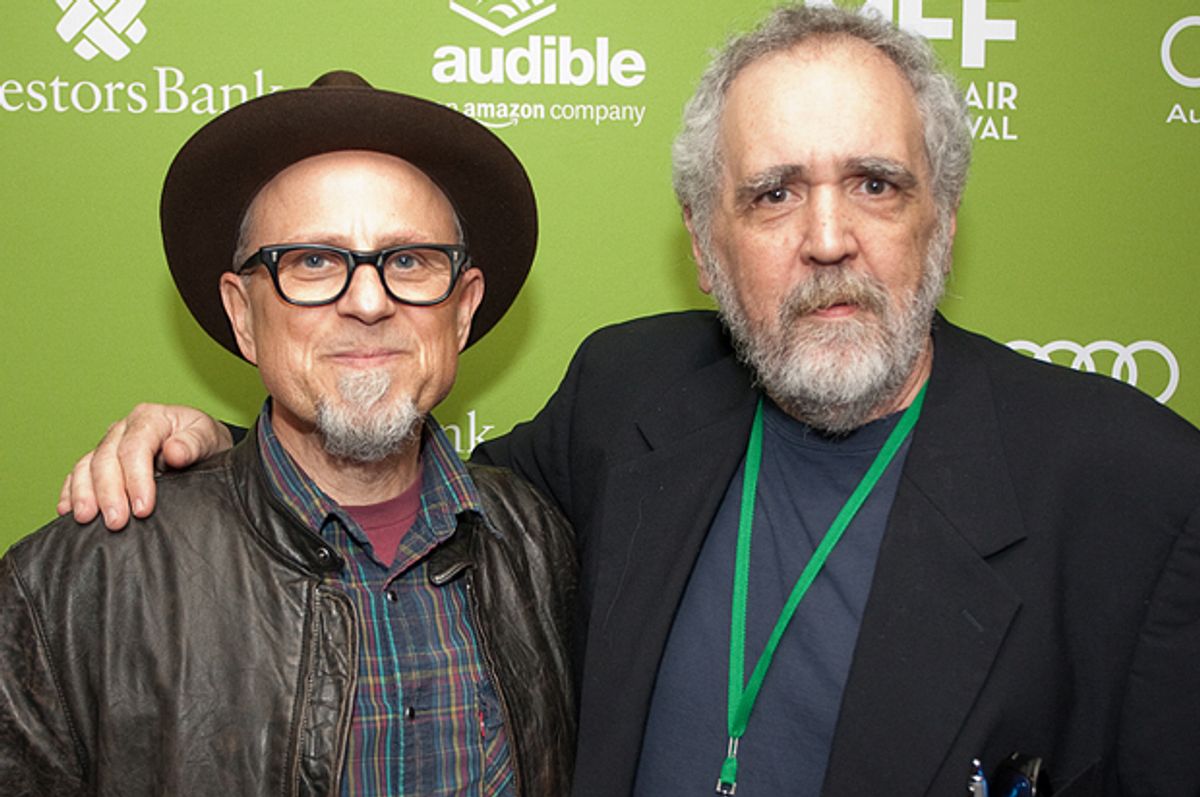

The comedian/filmmaker chatted (on Robin Williams’ birthday, no less) with Salon about dangerous humor, Barry Crimmins and “Call Me Lucky.”

“Comedy is tragedy plus time,” as the saying goes. Why do you find (and mine) humor from dark material?

That’s what I gravitate to. In the past, the movies I’ve made are perceived as dark, but a lot of comedies are way darker. I don’t make light of the subjects. The events that happen in the films I make are not an exploration of those things, they are just elements in the movies. When I make a film, I don’t go, “This is shocking”; it’s what comes out of me. Those are the stories I’m interested in telling. The movies I make, I never see them as accurately portraying a life, but more like fables. People think those [taboo] things are where the comedies come from—and a lot of comedies would film those events—but that’s not what interests me. “World’s Greatest Dad” is similar to “Call Me Lucky” because they are about a middle-aged man taking charge of his life; the difference is that Barry’s a real person.

What can you say about taking charge of your life? You mention in the film how Barry prompted you to get sober. What can you say about taming your own wild ways?

I was drinking and doing drugs when I was a young man, and I was out of control. When I was at my most outrageous and destructive, I alienated almost everybody. Barry was one of the few people who stood by me, and didn’t judge me. He facilitated that.

When we were making “World’s Greatest Dad,” a couple days in, Robin Williams said, “Oh, I’m playing you.” I did that. I had fame and wealth and things that are supposed to make you happy, but I wasn’t happy, because there’s no importance on having a fulfilling life. So in my mid-40s, that was my pursuit—making films that interested me, films that I would like to go see.

What do you think about the current idea that “politically correct” culture is ruining comedy?

I don’t agree with that at all. I think people should be able to talk about whatever they want onstage, but they shouldn’t be surprised when other people have opinions about what they are saying. I’ve always said what I’ve wanted to say onstage, and I’ve heard repercussions from disgruntled people. People talk about political correctness as if they are being oppressed. I don’t think there should be censorship. But people shouldn’t be surprised when folks don’t swallow everything you say.

You’ve had some moments in your career where you’ve “gone too far” or said something “too soon?” Crimmins does too, it seems. What observations can you make about that?”

Most of the time, when someone is offended by what I say or do, that was my intention—to target a certain mind-set. When someone says they don’t like what I do, and then describe what happens in the film, it’s funny to me—as if I didn’t know what happened! It wasn’t a secret. I’m not interested in having mass appeal, or being a popular filmmaker or comedian. I’m interested in saying what I have to say. I’m hugely influenced by Crimmins. That’s why I made this film; I am wired that same way. When I was a young man, I learned about sticking to your guns, but I totally got sidetracked. So it makes sense that Barry and I are merging again, because I am going back to the man he was trying to mold.

What did you find to identify with in Barry Crimmins that made you want to tell his story?

I always wanted to tell it…. When Barry went to the floor of the Senate Judiciary Committee [in the mid-'90s, to testify about child pornography being traded online in AOL chat rooms], I wanted to make a film about that. It was a Capra-esque thing. I took swipes at screenplays. I didn’t want to do a doc, so he wouldn’t have to relive the events. But hearing him on Marc Maron or Dana Gould, I saw he was comfortable talking about these events [in his past]. Robin [Williams] knew I wanted to tell Barry’s story and he suggested I do it as a doc. He gave me the initial money we used to start filming.

Can you talk about all the footage you assembled? Some of it was amazing!

When I watched “Amy,” I was thinking about that. They had access to a lot—home movies and things they shot on their phones. When we started “Call Me Lucky,” we had only two clips. I thought a lot of the stuff had to be animated. I thought I’d have to animate [more]. But as we did interviews, folks said, “Barry was on my cable access show…” and we got footage. The Senate floor stuff—we were told it didn’t exist. So it was exciting when we found that.

Do you feel pressure to include humor in telling a dark story of a comedian?

I was concerned, tonally, with telling Barry’s story. I tried to put [comedic] stuff in the beginning so it would be less jarring. I felt it was key to make the movie entertaining because I know the message isn’t something people want to hear. I felt it was key that it was funny. I wanted Barry to be seen being funny in the film, instead of people talking in the film about how funny he was. I don’t feel the pressure to put comedy in the films I make—it isn’t a preoccupation—it’s a byproduct, or a seasoning I get to use. Humor bubbles through. Some people watch my films and don’t think they are funny. But comedies like mine that are not punch-line driven are going for a small audience. When they aren’t told what they are supposed to be laughing at, it’s not lucrative. It’s more honest and there’s way more healing in dark humor. It may tackle unpleasant subjects, but I have no interest in just making people laugh.

Is there a responsibility to give people what they want, or expect laughs from a comedian? Barry doesn’t do it, and you don’t seem to subvert expectation as well.

As a young man, I did give the audience what they wanted and expected. But now I’m not interested in that. I was trying to make the leap from making stuff fulfilling but not indulgent. How do you keep making stuff? I don’t really have to wait around to make a movie. I work with minuscule budgets, but that’s not why I make movies. I love telling stories. They are not tools to reinvent me, or be financially sound.

Barry’s act eventually turned into his activism. He became a voice for the unspoken. What do you think about the responsibility for people, comedians in particular, to speak up and speak out?

I think Barry’s act was always peppered with political content, even when I first met him. After his disclosure, just entertaining people lost any interest to him. He was full-on political. What’s interesting about his disclosure is that his material was always topical and relevant but never personal. His disclosure was one of the first times he was personal, and not talking about historical figures or something in the news, but himself.

There is very much a “Sad Clown” vibe going on with Barry. Kevin Meaney gets at this as well in how he came to terms with his sexuality in the film. We could also draw parallels to Robin Williams. What observations do you have on this topic and processing pain through comedy?

I don’t know if it is that funny people process pain through comedy, I think funny people when they process pain it ends up being funny. I love Kevin Meaney in the film so much. His story was important to me because it too was a version of Barry’s story and a version of courage. With Barry, there’s a shift that he’s come through the other side, and that the byproduct of his healing is that he helps all these people. If Barry had metamorphosed into a guy who was no longer a curmudgeon, it would have done the world a great disservice.

Shares