Maybe it was inevitable: Between cult status that grew into a towering literary reputation, martyr status that followed a suicide, and now a new movie, it was probably only a matter of time before it became fashionable to make fun of David Foster Wallace.

Here’s a prediction: Though Wallace, who died in 2008, seems very much a creature of the print age, or at least its unsteady transition to the digital era, the takedown culture of the Internet means that he’ll get chewed up pretty bad over the next few months.

The first glimmer of this is a funny but unpersuasive piece on New York magazine’s The Cut called “David Foster Wallace, Beloved Author of Bros.” After describing Wallace’s mockery of the male chauvinism of John Updike and other “Great Male Narcissists,” Molly Fischer writes:

How strange, then, that Wallace, too, has become lit-bro shorthand. This occurred to me last week, after listening to a friend discuss the foibles of a bookish male acquaintance with a man-bun. “That guy,” she said. “I just feel like he’s first in line to see the David Foster Wallace movie.”

She mentions an anecdote that Jason Segel – who plays the novelist in the movie – uses in his press interviews:

He’d been preparing for the role by reading Wallace’s work, and he was picking up Infinite Jest at a bookstore. He put the book on the counter and the woman at the register rolled her eyes. “Infinite Jest,” he remembers her saying. “Every guy I’ve ever dated has an unread copy on his bookshelf.”

Now, this story, and this well-reasoned one by Anna North, and some of the others likely to roll out over the next few weeks, don’t quite attack the novelist himself, they make fun of his fans. But they seem weirdly troubled by the idea that a writer would have a following, and that within that following might be some people who take the writer seriously.

What, then, is a bro? An earlier story from The Cut tried to get at the way the term was evolving. Here’s Ann Friedman:

“Bro” once meant something specific: a self-absorbed young white guy in board shorts with a taste for cheap beer. But it’s become a shorthand for the sort of privileged ignorance that thrives in groups dominated by wealthy, white, straight men. “Bro” is convenient because describing a professional or social dynamic as “overly white, straight, and male” seems both too politically charged and too general; instead, “bro” conjures a particular type of dude who operates socially by excluding those who are different. And, crucially, a bro in isolation is barely a bro at all — he needs his peers to reinforce his beliefs and laugh at his jokes.

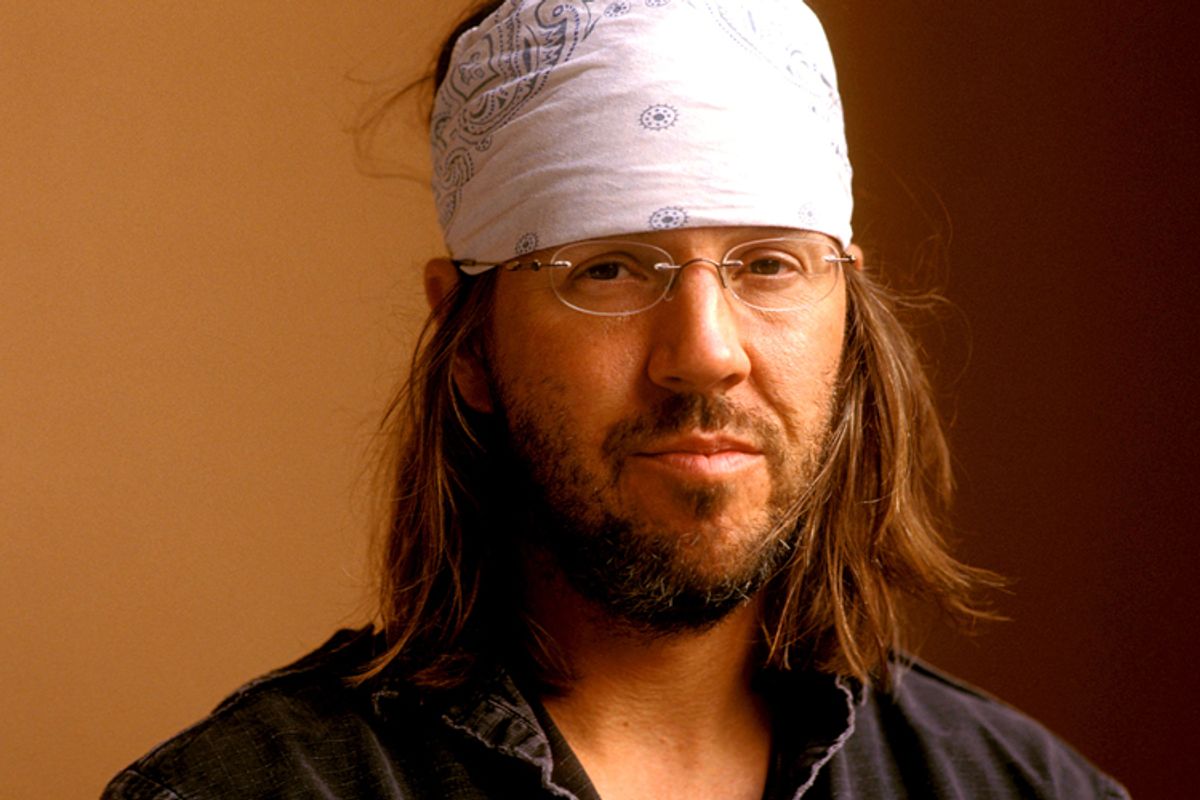

Are there pretentious guys in MFA workshops who idolize him, and disingenuous dudes who pretend to be into Wallace’s work but haven’t really read it? Was David Foster Wallace a straight white male? Did he come from the Midwest and play tennis when he was young? Did he wear a bandana that looked kind of silly some of the time? “Yes” to all of the above. But does this make Wallace or his fans “bros,” whether the sensitive bro, the nerdbro, or any other subgenre of bro? (Jason Segel, I will concede, seems like maybe a bro.)

Here are some things that these takedowns of Wallace or his following seem to overlook:

One of his best essays, “Consider the Lobster,” was a morally complicated about the pain that shellfish feel that was – agree with it or not -- the opposite of bro-ish heartlessness.

Another Wallace essay, “"E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction," stands as one of the most insightful things anyone has written about literature, pop culture, escapism, postmodernism, and half a dozen other topics that he managed to see through clearly and bring together in original ways.

Wallace started out a devotee of Thomas Pynchon and other Black Humorists – you see it quite clearly in his debut novel, “The Broom of the System” – and moved gradually into the moral engagement of Dostoevsky. Most of the bros on Wall Street and scooping up huge salaries in Silicon Valley took that path too, I think.

His most famous novel, “Infinite Jest,” was probably too long. But it was also massively ambitious, intensely funny, critical of consumerism, and deeply soulful.

He was not a class-skipping frat-boy but a recluse alcoholic. He was also depressive who eventually hung himself.

He wrote better than any of these people who’ve tried to take him down.

With all the things wrong with the world right now, why pick on David Foster Wallace and the people who like his books? Are literary figures really the problem with American society these days?

If Wallace has attracted a large number of bros with this kind of resume, it’s bizarre indeed. In her story on the changing face of bro culture, Ann Friedman wrote that “the key to de-broing our culture just might be the straight white guys who aren’tbros.”

For that one, I nominate the ghost of a certain tennis-playing Midwestern novelist. Either way, he deserves better.

Shares