Mass incarceration is an issue whose time has finally come. There are many signs that the wind is shifting on the question of America’s vast, wasteful and immensely destructive prison state, both among the public and the political class -- and that shift is not limited to the left. Criminal justice reform was supposed to be the issue that separated Rand Paul from the other Republican presidential candidates, at least until he got Trumped. It has become a central focus, believe it or not, of the Charles Koch Institute, the billionaire GOP donor’s libertarian nonprofit. This shift has created an important opening for political change, but it’s also a shift in the moral and cultural landscape, in ways that may be less evident but are just as important.

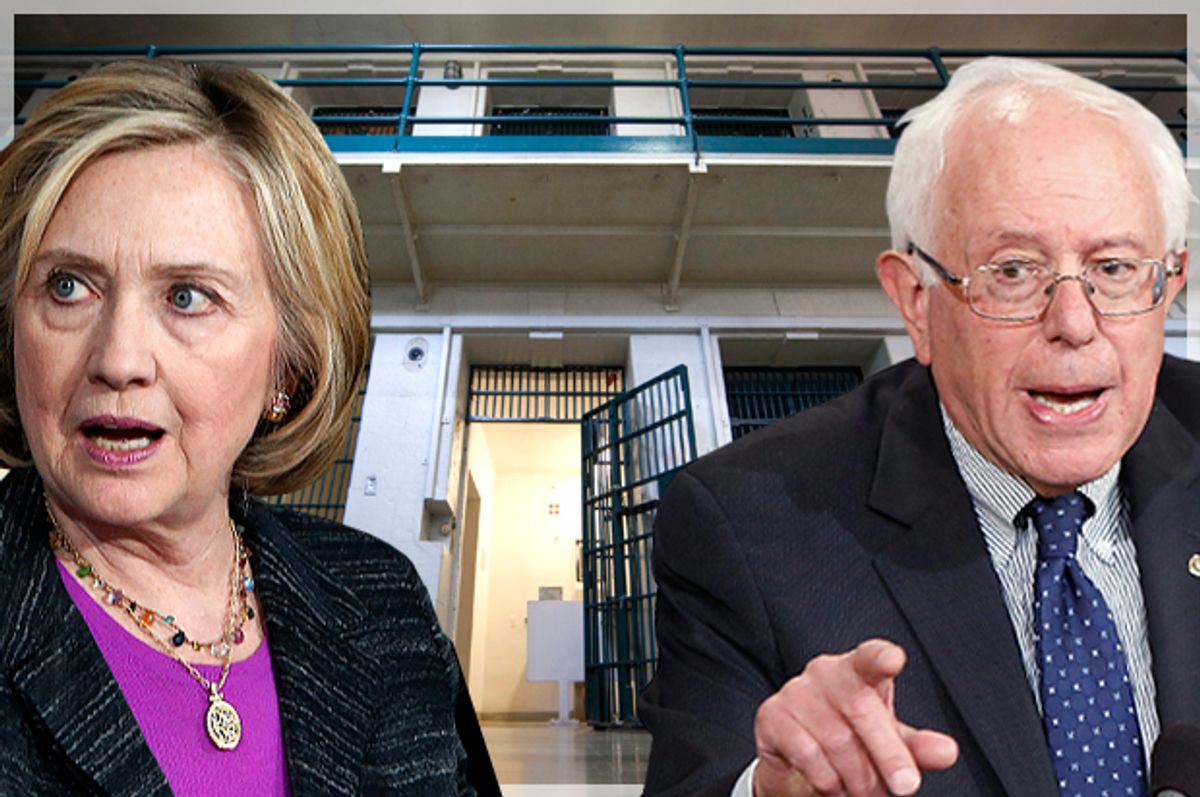

Barack Obama has evidently decided to use the bully pulpit of his final two years in the White House to shift the national debate on mass incarceration and the enormous racial disparities it both reveals and exacerbates. This could be seen as six years late and billions of dollars short, given the extent to which the president has avoided or soft-pedaled those issues throughout his time in office. As in so many other areas, Obama is more reactive than proactive, more a follower than a leader. He’s responding to the same conditions that have compelled Hillary Clinton to take up the cause despite what can only be described as an abysmal record on these issues, the same conditions that have unexpectedly made prisons, policing and criminal justice central themes of the 2016 campaign.

In fairness, Bernie Sanders has been a critic of America’s mass incarceration policies for years, although he has foregrounded the issue much more vigorously since being confronted by Black Lives Matter protesters. As is generally the case with any such shift, these politicians have been forced into new stances by ground-level activism, by the sheer weight of statistical evidence and intellectual argument, and by the altered mood of the public. In that regard, I think this summer’s tabloid-friendly story of Richard Matt and David Sweat, the two convicted murderers who dug their way out of a maximum-security prison in upstate New York, was a more significant event than it appeared to be on the surface. If their improbable saga seemed more like a Hollywood screenplay than reality – a pair of white killers, amid a demographic that is predominantly black and Latino, a Miss Lonelyhearts romance, an elaborate escape route through the steam tunnels – the ambiguous mixture of fear, longing and “Shawshank Redemption” sympathy they provoked reflected a widespread underlying unease with the nature of imprisonment in America.

Reality reasserted itself, you might say, after Matt was killed and Sweat was recaptured, with the allegations that other inmates at the Clinton Correctional Facility – a prison deliberately sited in the Adirondack North Woods, far from any population center -- had been viciously choked, beaten and suffocated by guards seeking information about the escape. That story has been less vigorously pursued, to be sure, by the TV reporters who breathlessly relayed every half-baked rumor about Matt and Sweat’s whereabouts. But it now appears that the Clinton escape inadvertently revealed the tip of an extremely ugly iceberg. Only the most naïve or most hypocritical observer would try to claim that the widening scandal around official abuse and corruption within New York’s prison system (including the alleged murder of at least one inmate, and its subsequent coverup) is unlikely to be replicated in other places.

The political opportunity presented by this moment of rapidly shifting perceptions – the opportunity to change laws, to change hearts and minds, and if possible to re-examine our entire approach to criminal justice -- must not be squandered if we want to build a more just society. But real change will not come easily: As Adam Gopnik wrote three years ago in the New Yorker, mass incarceration on a scale never before seen in human history, a policy that has disproportionately affected communities of color that were already marginalized, impoverished and disenfranchised, could be called “the fundamental fact” in American society.

Some studies suggest that rates of incarceration have dipped slightly as a result of recent reforms, but by any standard you like America remains the unchallenged superpower when it comes to locking up its own citizens. We have a prison population of roughly 700 inmates per 100,000 people, with Russia – Russia! – a distant second among major nations at about 455. We even lead the world in terms of absolute prison population, with at least 2.2 million people behind bars at any given time, while China, with four times our population, has around 1.6 million prisoners. You can slice and dice these numbers in all kinds of amazing ways: The United States has just 4 percent of the world’s population but nearly one-quarter of its prisoners; 37 American states have higher incarceration rates than any nation in the world, large or small.

That fundamental fact of our society is insulated by thick walls of ideology and money. Law-and-order think tanks are standing by to argue that all the zillions we have poured into the prison state, and all the harsh sentences handed down for minor offenses, are the primary cause of the decline in crime over the last several decades. That’s a can of worms to drill open some other time, but here are a couple of salient points: Correlation does not equal causation, as the ancient social science maxim holds, and there is much more evidence to suggest that long-term incarceration breeds career criminals than that it deters them. Secondly, this is the only context where you ever hear prison-industry lobbyists, or the Republican legislators they bankroll, admit that crime has trended consistently downward for 50 years. Their entire con game relies on the media-fueled perception that “urban violence” is out of control and mobs of armed black men are roaming the streets in search of white victims.

Cutting through these lies and misperceptions and undoing the social devastation of mass incarceration is likely to require forging difficult alliances across ideological boundaries, not to mention working with many of the same people who created this disaster in the first place. There are innumerable reasons to indict our bipartisan political system for its mendacity and cowardice, but I can think of none worse than this: For at least 35 years, the only perceptible division between mainstream Democrats and Republicans on the prison issue was over whether we should simply build more and more prisons and stuff more and more people into them (the "moderate" view) or whether we should do that and hand the whole enterprise over to private, for-profit corporations.

Understanding that shared political culpability is one important aspect of the point that Black Lives Matter activists have tried to make in their recent confrontations with Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders. Whatever we make of those tactics – bearing in mind that BLM is a decentralized movement whose members don’t necessarily reflect a unified strategy – I think it’s crucial for white leftists to face the fact that the Democratic Party has blood on its hands on this issue (among others), and that liberal sanctimony simply will not do.

I hesitate to give Hillary Clinton credit for much of anything beyond her well-known gift for shrewd political calculation – which led to fateful arrogance in 2008, and may yet do so again in this campaign. But her rhetorical turnabout on the issue of mass incarceration, including the fact that she now routinely utters those words aloud, is an important signal of the changing tide. Clinton vigorously supported her husband’s massive anti-crime bill of 1994, which provided almost $10 billion in prison funding, stripped state and federal prison inmates of the right to higher education, made gang membership a crime in itself (almost certainly a violation of the First Amendment), and implemented the infamous “Three Strikes, You’re Out” policy mandating life sentences for repeat offenders, even for certain nonviolent crimes. (I learned something new about that law while doing some background reading: It required the Justice Department to issue annual reports on “the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers.” No such reports have ever appeared.)

Clinton has looked a bit defensive during the early stages of her Democratic campaign, although she is unquestionably playing the long game and it’s way too early to announce that she’s in trouble. Her videotaped conversation last week with BLM activists has been endlessly picked apart by Clinton-bashers on the left, and I’d love to play along. But in terms of sheer political calculus and her middle-class, liberal base, she probably did herself no damage. She adroitly steered the discussion away from the Bill Clinton administration’s thoroughly noxious record on criminal justice and toward her long history of support for mainstream civil-rights issues and her political alliances with the African-American community.

There were good reasons for that. The aforementioned Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (whose principal legislative sponsor, by the way, was Sen. Joe Biden) almost certainly did more to drive the boom in prison-building and mass incarceration than the policies of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush put together. Furthermore, it epitomized the cynical Clintonite strategy of “triangulation,” which in this case specifically meant co-opting a core Republican issue while marginalizing or repudiating poor black people, the most vulnerable element of the most loyal Democratic constituency.

Given that history, I don’t think African-American activists – or anyone else – can be blamed for feeling less than convinced by Hillary Clinton’s 2016 change of heart. Both Clintons have expressed regret over certain consequences of the 1994 law that were perhaps unintended or unforeseen – and, fine, let’s take them at their word. But social scientists, activists and investigative journalists have told us all along that the vast prison-industrial complex created by bipartisan consensus was brutal, corrupt and inefficient -- to state the case in its narrowest possible terms. Many went on to observe that its principal product, and arguably its intended purpose, was a “new Jim Crow,” to borrow the title of Michelle Alexander’s groundbreaking study. In practice, mass incarceration amounted to the selective and systematic oppression of poor people in general and African-Americans in particular. It hardened patterns of enduring racial injustice and widening economic inequality.

Nobody in mainstream political or media circles particularly wanted to hear any of that. Such ideas were viewed as tedious and unrealistic left-wing spinach, until they abruptly became unavoidable. The mythical suburban swing voters understood to be decisive in national elections wanted tough talk on crime, and they got it. No candidate in American political history has ever lost an election by promising to be tougher on crime than his or her opponent, to build prisons that resemble the Château d’If from “The Count of Monte Cristo” as closely as possible and then fill them up with drug lords, sexual abusers, juvenile “superpredators” and other fearsome monstrosities. Those poisonous fantasies have not entirely lost their grip, to be sure, but they are starting to come unglued.

What happened in reality was quite different: It was the evil default setting of the American criminal justice system, cranked up to 11 and fed with crystal meth. We bankrupted ourselves and ripped our society apart with a “war on drugs” that everyone with a brain knew would not work but was supported by every major politician in both parties. We locked up black and brown men by the millions (along with significant numbers of poor rural whites), mostly for the kinds of nonviolent drug offenses that are widely tolerated or overlooked among the more affluent classes.

When we look at the current political landscape and see the bizarre coalition that has concluded that all this was a dreadful mistake, from the Clintons to Rand Paul and his dad to the Koch brothers, we may well respond with a mixture of hilarity, nausea and disbelief. But this is no time for ideological purity; addressing this national emergency will require all those odd alliances and many more. If the question is who Hillary Clinton thinks she is fooling and whether she can be trusted, the only possible answers are “nobody, I hope” and “hell, no.” I'm not saying I wouldn't rather have Bernie Sanders, or that Clinton is inevitable (especially given how this crazy campaign has gone so far). But we may be stuck with her anyway, and then the question becomes whether we have the will, and the political power, to compel her to do the right thing.

Shares