“We normals -- aided, doubtless, by our wish to be fooled, were indeed well and truly fooled… And so cunningly was deceptive word-use combined with deceptive tone, that only the brain-damaged remained intact, undeceived.”

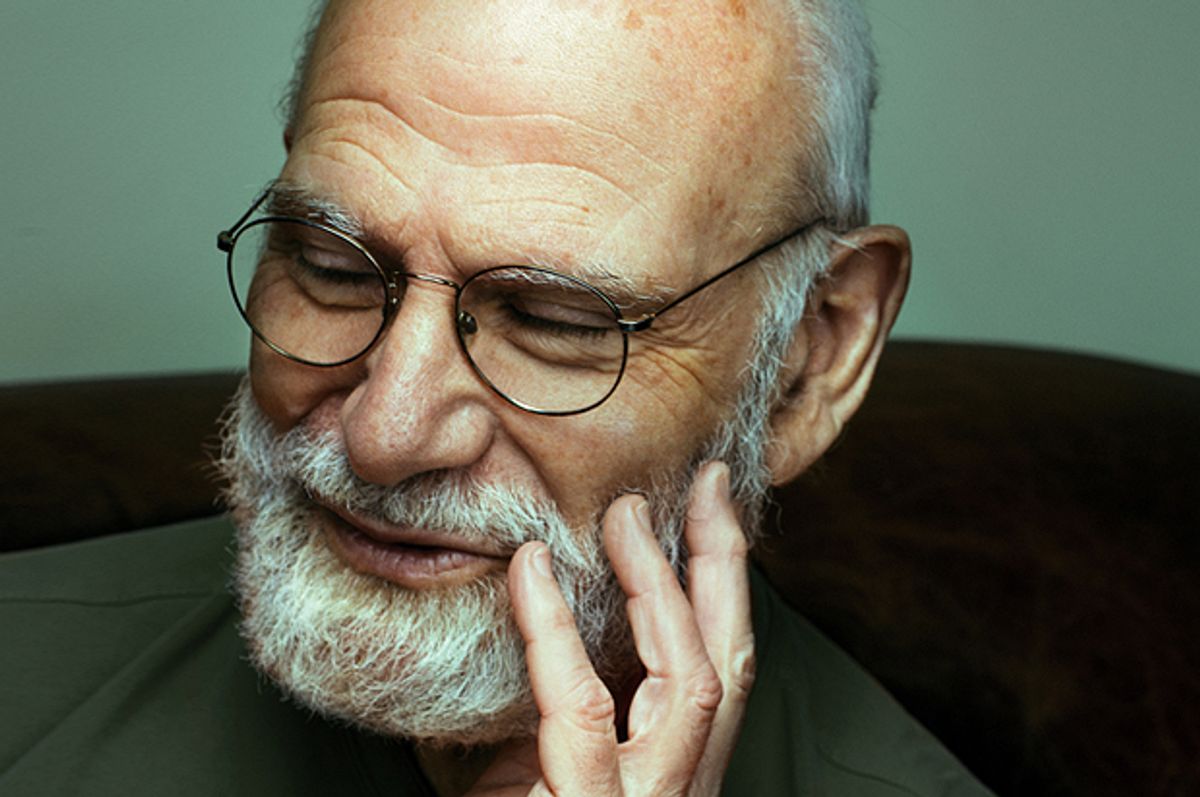

So wrote neurologist Oliver Sacks at the conclusion of “The President’s Speech,” a chapter from "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat," his classic book chronicling the fascinating stories he encountered throughout his work in neuroscience.

Sacks, who died yesterday at the age of 82, was renowned not only as a brilliant scholar of the human brain and nervous system, but also as a doctor of extraordinary compassion. Instead of simply viewing the mentally and neurologically ill as sick people in need of a cure, Sacks recognized that their unique perspective on reality often helped them arrive at valuable insights that eluded the “normals.”

In “The President’s Speech,” Sacks described the “roar of laughter” that emerged from a hospital ward that was housing patients with aphasia -- a collection of language disorders generally characterized by a severe difficulty or downright inability to understand words -- as they listened to a speech being delivered by Ronald Reagan. "Some looked bewildered, some looked outraged, one or two looked apprehensive, but most looked amused," Sacks wrote.

Although the patients struggled to comprehend the verbal content of the president’s oratory, “natural speech," as Sacks explained, "does not consist of words alone. It consists of utterance – an uttering-forth of one’s whole meaning with one’s whole being – the understanding of which involves infinitely more than mere word-recognition.” Because the aphasia patients weren’t distracted by the rhetoric and theatricality of Reagan’s address, the subtle nonverbal information that eluded most of his listeners was particularly pronounced among the aphasiacs. "Thus the feeling I sometimes have," Sacks wrote, "that one cannot lie to an aphasiac. He cannot grasp your words, and so cannot be deceived by them; but what he grasps he grasps with infallible precision, namely the expression that goes with the words, that total, spontaneous, involuntary expressiveness which can never be simulated or faked, as words alone can, all too easily."

In Reagan's case, the patients were not impressed.

The most obvious lesson here is that, although democracies depend on the good judgment of voters in order to survive, the electorate is too easily duped by cheap parlor tricks. While Reagan happened to be a conservative, this is most likely true everywhere on the political spectrum. Thanks to the advent of mass media like radio, television, and the Internet, any politician who wants to win in a large-scale election needs to have charisma, gravitas, an intangible “it” quality -- all of which have nothing to do with their policies and everything to do with the intuition of the voters who listen to them. Ideally, these gut reactions would be infallible; the reality, of course, is that we are easily misled by deft performances, mistaking the superficial show of leadership for the real thing.

On a deeper level, though, Sacks’ experience at the aphasia ward reminds us that the so-called psychologically “abnormal” have an important role to play in our political life. When we think of outsiders, our minds tend to wander toward business leaders, famous entertainers, and fringe political activists peddling non-mainstream ideologies. Yet in the truest sense of the term, none of these individuals are actual outsiders; by sheer virtue of the fact that they’re contributing to our public dialogue in a way that the vast majority of their fellow citizens can understand (even if they disagree), they are still “normal” enough to be able to play the game, however large or small their roles might be.

A real outsider, on the other hand, is someone who has been rendered incapable of fully participating in our civic life. Perhaps it’s a mentally disabled person who can’t comprehend the words coming from a politician’s mouth, or a homeless man or woman so beaten down by poverty that their attempts to communicate seem like gibberish to most passersby, or someone who isn’t sick at all but falls far enough beyond the spectrum of normative experience that their distinct perspective is reflexively dismissed. (See: the LGBT community’s critiques of heteronormativity, which a few generations ago lacked any kind of meaningful audience.) Regardless of the reason, the real outsiders aren’t the one who disagree with the status quo, but rather those who wouldn’t be able to participate in it even if they tried.

This, incidentally, is why I suspect the patients at the aphasia ward couldn’t stop laughing. Here was a president, twice elected by substantial majorities, who despite being widely lauded as The Great Communicator, was as transparent as a window to them. The aphasiacs may have been isolated from the rest of the world and dismissed as crazy, but they could see a stark truth that the “normals” could not… meaning that, on this one incredibly important occasion, they were the sane ones who could see what society itself was too crazy to recognize.

In the words of Abraham Lincoln: “I laugh because I must not cry. That is all. That is all.”

Shares