When we meet Gretchen in the opening minutes of "You're the Worst," she's just stolen a blender from a wedding. She goes home with a stranger, to whom she admits so many things she starts to sound like a basic-cable Marla Singer: DUIs, drugs, STDs from her high school guidance counselor. By the usual rules of half-hour comedies, this would be the punchline of a crazy hookup, the beginning of a redemption arc, or signposts trying to make her a relatable wild child for a young demographic. (You know kids today and their DUIs.)

In the morning, though, we follow her as she blithely goes on through her life, including a parade of troublesome men and a best friend who gives her a run for her money; this comedy is clearly skewing dark. But even in a show titled "You're the Worst," Gretchen is unapologetic. And the real twist in "You're the Worst" isn't that she ends up in a tentative relationship with her hookup guy—she's as eager for connection as she is terrified of it. It's that her awfulness is framed as worthy of both humor and deconstruction. Those anecdotes weren't the shorthand that can so often be the beginning and end of characterization for a woman on TV. They're the beginning of a full-season arc as she comes to know herself better. She's a comedic antihero; that's the plot.

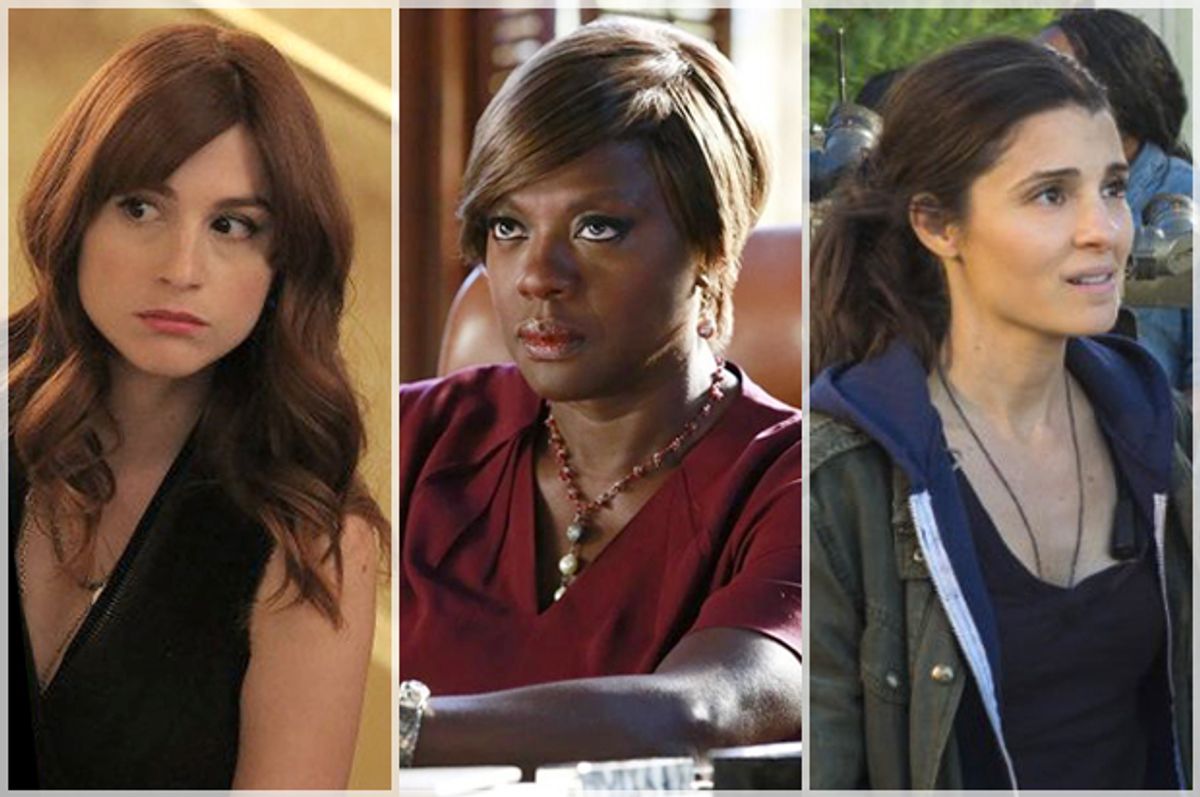

It's not a unique frame story—for a man. But in an age fascinated with the antihero, from "Breaking Bad" to "Happy-ish," women counterparts are still so rare that they're enough to hang a series on. Of all the great things in "UnREAL"'s first season—breakneck pace, toxic ambition by proxy, and ruthless examination of showbiz manipulation—the most important was leads who were both unrepentant assholes, and women. The pressures behind a reality dating series would be unequivocally, unbearably misogynistic coming from two guys. (The manipulation that does come from men on this show is definitely both those things.) But Quinn, the hard-as-nails producer who uses blackmail as an everyday MO, and Rachel, whose gift for manipulation is so sublime the camera can only watch in wonder, are the central jerks.

Their active awfulness shifts the story into something far more nuanced than the show's pulpy premise might suggest: it becomes an antihero character piece, a psychological thriller with live-TV stakes, and a show about power dynamics in which any men are afterthoughts. That overt interest in the inner workings of unsympathetic women puts "UnREAL" beside "You're the Worst" in a TV landscape that's getting wide enough to offer the feminine version of the fascinating jerk that prestige TV has offered for years.

It's not a new conversation; the representation, and presentation, of women on television has been in negotiation since TV was invented. And there have always been characters who pushed back against dominant expectations. (The Donna Reeds of early television are well known, but one of the earliest small-screen leading ladies was a streetwise, edgy undercover cop in 1957's "Decoy: Police Woman.") But even today, shows who attempt to take their women protagonists past a certain level of darkness can run into trouble: In a field so dogged by the Likability Factor that marketing companies attempt to quantify actress' popularity into "Q scores," it could be tricky business to commit to a woman antihero as messy and meaningful as the men.

Given the dominant expectations for women in media (charming ingenue, supportive wife, acerbically warmhearted elder), it's not surprising that so many of the women who demonstrate psychological complexity have been villains. TV loves a good villainess, from the noir-tinged ruthlessness of early soap operas to the all-out camp of "American Horror Story." Even recent lead characters who are more traditionally cast in the antihero mold—like Norma Bates in "Bates Motel"—benefit from a thin veneer of that camp, which reassures us it's in on its jokes. But because the villainess is such an established figure, without support from the narrative, that's what many female antiheroes can become. Take Cersei Lannister, insightfully played by Lena Headey and given enough reason to be one of the show's many complex schemers—but she's been so frequently belittled by other characters, and robbed of a consistent psychology by several adaptation choices, that she's become a villain by sheer lack of options. It's an interesting contrast to the BBC's "Musketeers", in which Milady de Winter not only survives her canon expiration date but goes on to become a central character—sometimes driven to terrible things, of course, but given the same internal life as any of the men. Tormented but never dismissed (and even considered worthy of a romance!), she's a character, not a caricature.

That's a careful line to walk when a show hopes to highlight a female character for terrible behavior. And part of the reason in the noticeable uptick is that the traditional formulas and tropes are more likely to be shaken up outside of prestige cable. As we get closer to Peak TV (a programming landscape so bogglingly expansive, with over 400 scripted shows this fall, that NPR covered the phenomenon in a week of essays), the sheer volume means networks are taking chances, and suddenly the lady jerk is—comparatively—seeing herself everywhere.

They're a particularly interesting fit for comedy, in which it's easier to dismiss terrible behavior as part of life's great absurdity, but more difficult to make that absurdity part of a character whose faults are sympathetic enough to be human. It's why the same branch of television's family tree gives us Lucy Ricardo and Liz Lemon, but the Liz Lemon of "30 Rock"'s first season shifts darker as the show becomes more surreal, until she's very nearly an antihero herself by the final season. (There are still echoes of her in the disastrous Dee on "It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia," just as Gretchen takes some cues from just-before-its-time "Don't Trust the B- in Apartment 23"). Gretchen's still human, of course—humanity is the line between comedy and farce—and "You're the Worst" deliberately adopts a more dramatic tone in episodes where she has to confront her faults, a growing-up process so powerful for her it's sometimes accompanied by nausea.

But alongside this growing foothold in comedy, it's particularly satisfying to see women as the antihero at the center of a drama, where so many antiheroes have anchored television milestones. And Peak TV means that networks are taking artistic risks in order to compete for their share of an audience not only spoiled for choice, but actively looking for shows that break from the standard. There might be downsides to such television overload, but where there are risks there are rewards, and it's meant new room for characters who thrive in the dark. These dramas back their leads wholeheartedly in marketing, using their complicated heroines as a selling point. Prestige trappings are often attached to the stories of tormented men whose psychology drives the narrative; it's refreshing to come across a series structured around a woman who's never asked to be either likable or redeemed. (It's still rare enough to be notable when a woman gets a pivotal antihero role that doesn't require penitence to be considered interesting.)

Complicated women have been taking center stage for a few years, but series like "Homeland" often frame their heroine's darkness as a tragic flaw or a means to a justified end—Carrie's intentions are noble because America is at stake. Ensemble dramas have more luck introducing complicated characters (particularly those with women to spare, like "Orphan Black" and "Orange is the New Black"), but each began with an anchor character who was meant to be relatable in a more traditional sense. Rarer are those antiheroes whose actions are positioned as worthy of attention merely for being interesting, rather than well-meaning: ruthless Annalise from "How to Get Away with Murder," single-minded Emily in "Revenge." It's also why "UnREAL," which succeeds almost flawlessly as pitch-black satire, is more comfortably categorized as a drama. It's a study of consequences and rough choices, and is careful never to undermine or make light of Rachel's manipulation. This is no workplace comedy; Rachel is a weapon, and there's nothing funny about it.

It's a promising trend in television; many issues of representation hinge on the quality of presentation rather than simply the presence of a marginalized group. (If a show has several POC as stereotyped supporting acts, or a handful of one-dimensional women, it's missing the point.) The way to combat simplistic portrayals of women—who can forget "Mom Cop" or "Bad Judge"?—is to ditch the need for a "likability factor" and allow women to tell a full spectrum of stories with well-rounded characters. We shouldn't expect miracles: neither "You're the Worst" nor "UnREAL" did blockbuster audience numbers for their respective networks (FXX and Lifetime), but their audience was loyal, which is equally valuable in a landscape with 400 options on offer. And so, Peak TV may herald a marvelous new day for TV's terrible women, as networks that rely less on big numbers than demographic appeal begin to seek out viewers hungry for darker, complicated stories—and without asking showrunners to water down their leads. Next season, Gretchen and Rachel will still be kind of awful; that's kind of great.

Shares