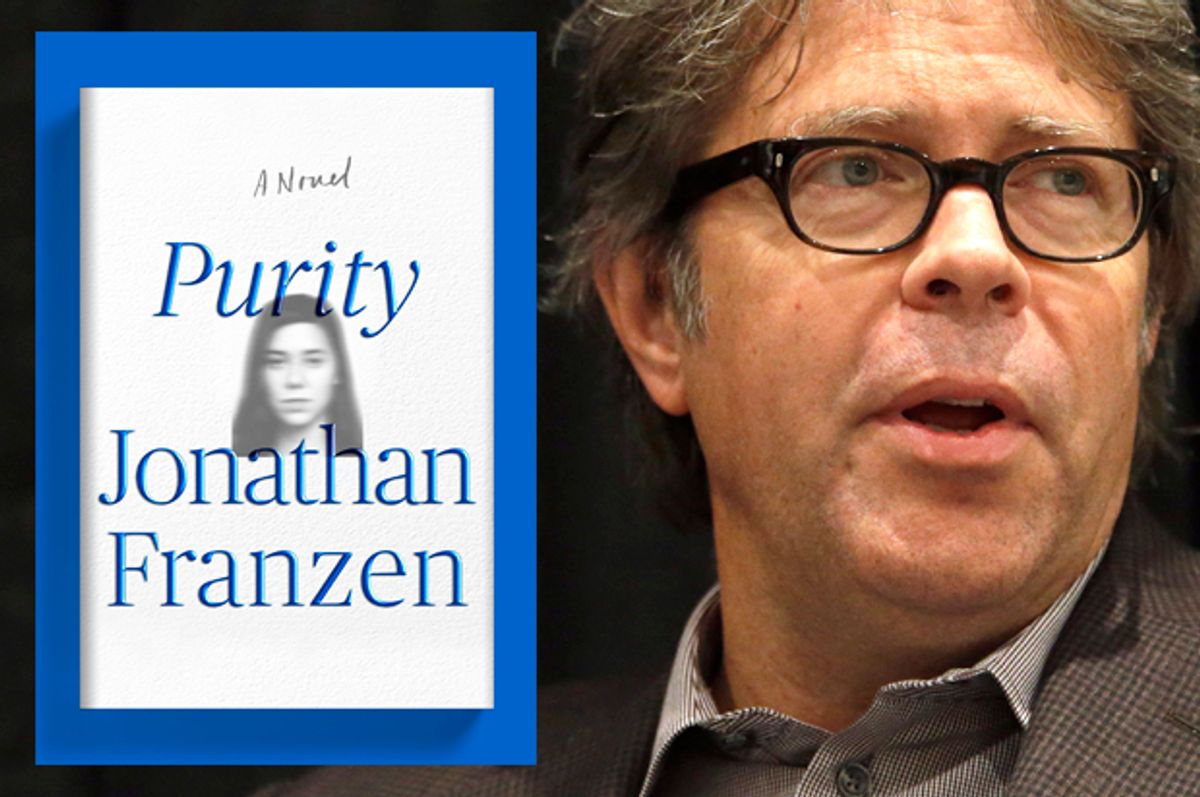

The arrival this fall of “Purity,” the new Jonathan Franzen novel, has brought everything we’ve come to expect when a new Franzen novel is published. The reviews have been serious and attentive, even those that are mixed. Caleb Crain in the Atlantic compared the author to Henry James, while the Times’ Michiko Kakutani called it his “most fleet-footed, least self-conscious and most intimate novel yet,” despite some quibbles.

It was not Kakutani’s least self-conscious review, however; when she praises Franzen’s book for being “big in terms of thickness and length,” she’s echoing the book’s fictional novelist, Charles Blenheim, who worries about writing his “big book” at a time when, he muses, “bigness was essential. Thickness, length.” She’s also lobbing Franzen’s novel-as-penis metaphor right back at him. These days, fairly outrageous levels of self-consciousness are considered normal, even necessary, to do any serious cultural work. Even if you don’t own a selfie stick, you know what they are, and you have an opinion about them. And your opinion is itself ironic.

All of which is to say, it’s a perfect time for a new Franzen novel! Because somehow in exposing and then embodying what annoys us about the culture in which we live, he satisfies something we crave. In his beautifully wrought social satire, he reminds us with each new book that we live in a time in which social satire is really superfluous. We live in a kaleidoscope of absurdity already.

You could even say that Franzen helped usher in our current age of self-consciousness. When “The Corrections” came out in 2001, it earned rave reviews; the New York Times called it “everything we want in a novel” in a smart, long piece by David Gates that ran just two days before the Twin Towers came down. To write a bestseller that appears just as we face a national tragedy, and then to appear on Oprah as her latest book club honoree, triumphantly touting the power of literature to help us make sense of our lives – that’s what some other novelist might have done. But not Franzen. He famously rebuffed the queen of television talk, saying that to appear on her show would besmirch his membership in ''the high-art literary tradition'' and that her book club sticker on his book’s dust jacket might turn off male readers.

To re-listen to his interview with Terry Gross on "Fresh Air" from that fall is to realize that Franzen both reignited our conversation about sexism in the literary world and arguably invented the humblebrag. When Gross asks about the Oprah choice – this conversation took place before Oprah essentially rescinded her offer – Franzen responded: “It was so unexpected that I was almost not surprised. I was like, ‘Oh hey Oprah, thank you for calling.’ … It literally had never once crossed my mind that this could be an Oprah pick.”

When Gross asked about his status as a male writer in a world in which women buy more books than men, he complained, “It has been a source of pain that there are interesting male novelists out there … and I’ll just leave myself out of that statement for a moment … who don’t find an audience because they don’t find a female audience.” And then the whole Oprah situation, well, it kind of emasculated him: “I had some hope of actually reaching a male audience, and I’ve heard more than one reader in signing lines now in bookstores say, ‘you know, if I hadn’t heard you, I would have been put off by the fact that it’s an Oprah pick, I figured those books are for women, I would never touch it.’ Those are male readers speaking.”

It’s really no wonder that ever since then, the literary world has responded to each new book, essay or utterance by Franzen with an eye toward its potential for controversy, gossip or hilarity. When “Freedom” came out in 2010, Time magazine put Franzen on the cover, and Oprah once again bestowed her magical sticker (this time, he accepted, and even stayed on to answer audience questions).

The Time article, on top of all the previous weirdness about gender and fiction, drew quick fire on Twitter (which launched in the years between “The Corrections” and “Freedom”) from Jennifer Weiner, Jodi Picoult and other female authors, who criticized the literary establishment’s obsession with tortured male genius. Men who write about family dysfunction are heralded as the next big thing, they argued, while women who write about family dysfunction are treated, more often than not, as if this type of fiction is part of their DNA, the trifling birthright of the talky XX chromosomes.

Franzenfreude was born, and it gave a big boost to another new literary development that came out the same year “Freedom” was published: the VIDA count. No longer was it going to be business as usual, white male reviewers praising white male authors in the pages of every newspaper and magazine. We can't give Franzen credit for inspiring VIDA (read the origin story here), but that’s not to say he wasn’t an irresistible and galvanizing symbolic target.

With this year’s new novel, “Purity,” the wheels are once again turning on what the Observer calls “the literary industrial complex of hating Jonathan Franzen.” Jennifer Weiner, for one, hasn’t stopped – once again, Franzen provided a big target with his bizarre statement, likely a failed joke, about adopting an Iraqi War orphan to learn about the younger generation.

But among the serious and respectful reviews, this year’s Franzenfest has included more than a few think pieces about the meaning of Franzen – do we love him or hate him? And why? – and at least one very funny CliffsNotes retelling of the book (spoilers abound, though).

How much of this response is provoked by envy? Surely at least some of it is, from some quarters. Unlike so many of today’s MFA-wielding white dude novelists, Franzen knows how to construct a plot so that readers keep reading – there are sections of "Purity" as propulsive as any by Stephen King (although Franzen only wishes he could write in the voice of the rural working class as well as King does). But much of it is friendly joshing from a literary world that continues to move in hopeful directions beyond the white dudes with their MFAs (no offense, white dudes!). As a cultural phenomenon, Franzenfreude appears to be over.

As Franzen, when talking all those years ago about “The Corrections,” said to Terry Gross, “it’s a literary book. I think it’s an accessible literary book.” That is, in the end, pretty much his brand. Every five to 10 years, he will write a big novel that many of us will read. Some may hate-read it – Franzen knows about hate-reading, he even refers to it in the first few pages of “Purity,” in which the main character’s mother reads a local paper “for the small daily pleasure of being appalled by the world.”

When the Atlantic reviewed Dickens’ “ Great Expectations” – the book whose main character shares a name with “Purity’s” Pip – the review notes that many had recently taken to disparaging the author: “We have never sympathized in the mean delight which some critics seem to experience in detecting the signs which subtly indicate the decay of power in creative intellects. We sympathize still less in the stupid and ungenerous judgements of those who find a still meaner delight in willfully asserting that the last book of a popular writer is unworthy of the genius which produced his first.”

In the end, the Atlantic proclaims, “In our opinion, Great Expectations is a work which proves that we may expect from Dickens a series of romances far exceeding in power and artistic skill the productions which have already given him such a preeminence among the novelists of the age.”

In other words: lighten up. “Purity” is a very good novel, and Franzen a very good novelist. His missteps in the world of literary celebrity have been, on the whole, more amusing than anything else; if his standing as a symbol of book culture sexism helped launch VIDA to a wider audience, that’s the best legacy of all.

Shares