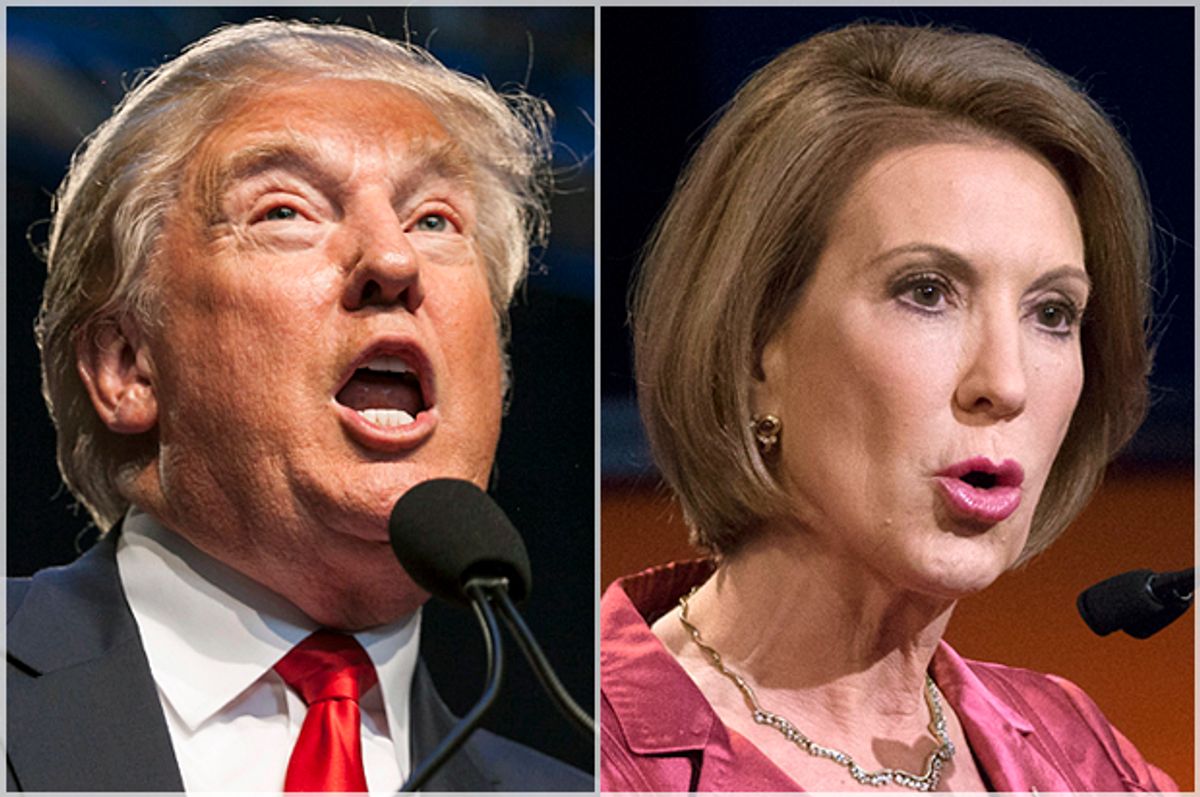

Could the next president of the United States be someone who’ve never held elected office? Anti-incumbent and even anti-politics fervor is not brand new in American political life, but lately, these tendencies have reached a fierce pitch: A national Fox News poll released Thursday, for instance, shows Donald Trump, Carly Fiorina, and Ben Carson commanding 53 percent of voters between them.

In the GOP, there’s a particular affection for the businessman savior: A CEO is not only a hero among men, but is somehow – perhaps because of a personal fortune – uncorruptible.

We spoke to historian David Greenberg, author of the celebrated “Nixon's Shadow: The History of an Image” and associate professor of history and journalism at Rutgers University. Greenberg, who contributes to Politico, has a new book, “Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency,” coming in January. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

A large swath of the GOP – at least those responding to polls – prefer presidential candidates who have never worked in government. Two of the three – Trump and Fiorina – have spent their lives as business executives. What does this tell us about the mood of the electorate these days?

There’s been so much change and variability on the Republican side that it’s hard to make generalizations. But the fact you’ve pointed to is one of the glaring patterns we’re seen: First Trump, then Carson, then Fiorina, once she’s gotten a little more exposure, have all grabbed a sizable chunk of the voters’ preferences, at least at this early stage. There’s something real going on here.

My hunch is that typically it’s the Republican establishment, which tends to be close to Wall Street, that gets excited about a CEO president. In this case, is it the establishment Republicans as well as the Tea Party fringes who are getting behind non-politician presidential candidates?

Oh, absolutely. I’ve not seen enough fine-grained analysis of Fiorina’s support. But Trump and Carson are pulling predominately from the Republicans who see themselves as outsiders, outside the system – not those who are inside big business or banking or Wall Street. So I hesitate to talk about populist appeal – that term is thrown around so much – but there seems to be a lot of anti-elitism in their message, and what they embody.

Historically, there have been many other businessmen who have run for or flirted for political office. And that’s been the root of their appeal – the sense that they’re running against a political establishment that’s corrupt.

How far does this go back in American history – the sense that a CEO can save us? That someone who has spent his time in business will be better at running the country than someone who comes out of the world of politics?

I think we probably start to see it in the late 19th century, where you start to see some of the robber barons looked to, not yet for political office, but as statesmen of sorts, men of wisdom and judgment. As men who stand above politics and have a certain pragmatic know-how that can be brought to bear on politics.

The earliest examples I can think of, of moguls who ran for office, are Henry Ford and William Randolph Hearst, in the early decades of the 20th century. Both of them did play – and I use the term advisedly – a populist card. There was an anti-intellectual component, certainly, to Ford’s message. There was a sense that politics was corrupt, that those who made their lives and careers in politics were not to be trusted. So that appeal goes back. It rarely wins, but it’s been there as a current in our politics for more than a hundred years.

That’s interesting -- the lines are drawn in similar ways today. I wonder if there’s something different now, though. I wonder if attention to the corrupting influence of money in politics, which has been mostly – though not exclusively – a critique from the liberal left – has penetrated more broadly. The larger message becomes: Businessmen have their own money, they don’t need to be part of a system of Super PACs and donors… That’s been part of Trump’s appeal. Does this idea motivate Republican primary voters, excite them about business people at the helm?

This idea, too, goes back to the Founders – not that they sought businessmen, but they did seek men of property and of standing, because of the fear of corruption. They thought that politics led to corruption, that somebody who went into politics for reasons of personal gain was bound to become beholden to various interests… That you wanted an independent – and independent was a key word in their vocabulary – virtuous land-holding man from the gentry or the well-to-do classes.

So, that was an idea that was there from the beginning. And I think you hear it whenever someone runs, not just for president, but for governor: I feel like every New York gubernatorial candidate on the Republican slate makes the argument that the Democrats are corrupt, that a businessman will be immune from these pressures.

Now, how much of this is really the argument that voters buy into? It seems to me it’s a little less rational than that -- it’s at the emotional level, where voters simply like the idea of someone outside the system who’s achieved success in a different realm. And on the Republican side, it tends to be a group of people who tends to admire business success; it doesn’t tend to occupy the same pride of place among Democrats and liberals. Because Republicans venerate the free market, they talk the language of opportunity and social mobility, they see people who’ve risen to the top of the business world as especially worthy.

What we do learn from the historical record when people become presidents, governors, Congressmen, et cetera?

It’s hard to generalize, and it’s certainly possible for a successful businessman or -woman to also find success in the political arena. However, there are also skills that politics requires that business doesn’t.

One example for someone who first made his name in business who also went into politics is Herbert Hoover, who served as commerce secretary for eight years before he ran for office. But the presidency was the first elective office he ever held. Although he wasn’t responsible for the stock market crash or the Depression, he certainly proved inept in handling them.

And some of that ineptitude had to do with his lack of feel for politics: He couldn’t communicate very well with the public. He wasn’t very supple with his ability to experiment with new policies. He lacked a certain set of skills that most successful politics have, because coming up the ladder typically requires them: brokering different ideas, being able to pivot… Sometimes we see these skills as negative: It’s why we sometimes see politician as expedient and fickle and opportunistic. But with someone like FDR, they turned out to be what the country needed, and Hoover lacked them.

That’s just one example, but the fact that other businessmen – Wendell Willkie, who ran against FDR in 1940, was a utility executive, Ross Perot, the most recent to be in a general election… I think their lack of success is a function ultimately that they came to political moments they had trouble handling. Politics is not just something one can pick up.

I wonder to what extent George W. Bush could best be understood as a CEO president, a businessman president. Could some of what you’re described be responsible for his difficulties in the White House?

That’s an interesting point. He certainly was called [a CEO president.] You sort of had similar things with Eisenhower, only it was the military metaphor.

A couple things distinguish Bush. He hadn’t been a particularly successful businessman It was the opposite: His family name had kept him viable in various business positions much longer than he would have survived had he not been a Bush. Trump and Fiorina – whatever you think of their records, at least they managed to rise to the top in a way that Bush never really did.

That said, he went to business school, he took something of a businessman’s attitude toward making decisions quickly, without too much fuss. That was part of his appeal to some people, or how he sold himself. Needless to say, most people, including many Republicans, don’t have too high an opinion of Bush’s presidency.

To be fair, those who would advocate a Trump or a Fiorina would say, it’s not fair to look at Bush an example, because he was not particularly successful in business. He may have talked that way, and used certain business-school methods, but he really didn’t have the whole bundle of talents we associate with success in business.

I think if anything, Bush’s greater success in the 2000 campaign and in his early presidency was that of a politician’s affect: He figured out, whether in his public relations job with the Texas Rangers, or his time as governor, certain political skills – how to get along with people, how to make certain compromises. In the end, I think he really fits the bill of politician rather than businessman.

Shares