Twenty years ago, Mary Karr helped kick off the memoir boom with her book “The Liar’s Club,” which described growing up in a small East Texas town with a charming, mendacious father and deeply pious, hard-drinking family. (“They're Liars, and That's Just the Least of Their Problems” ran the headline of the New York Times review.)

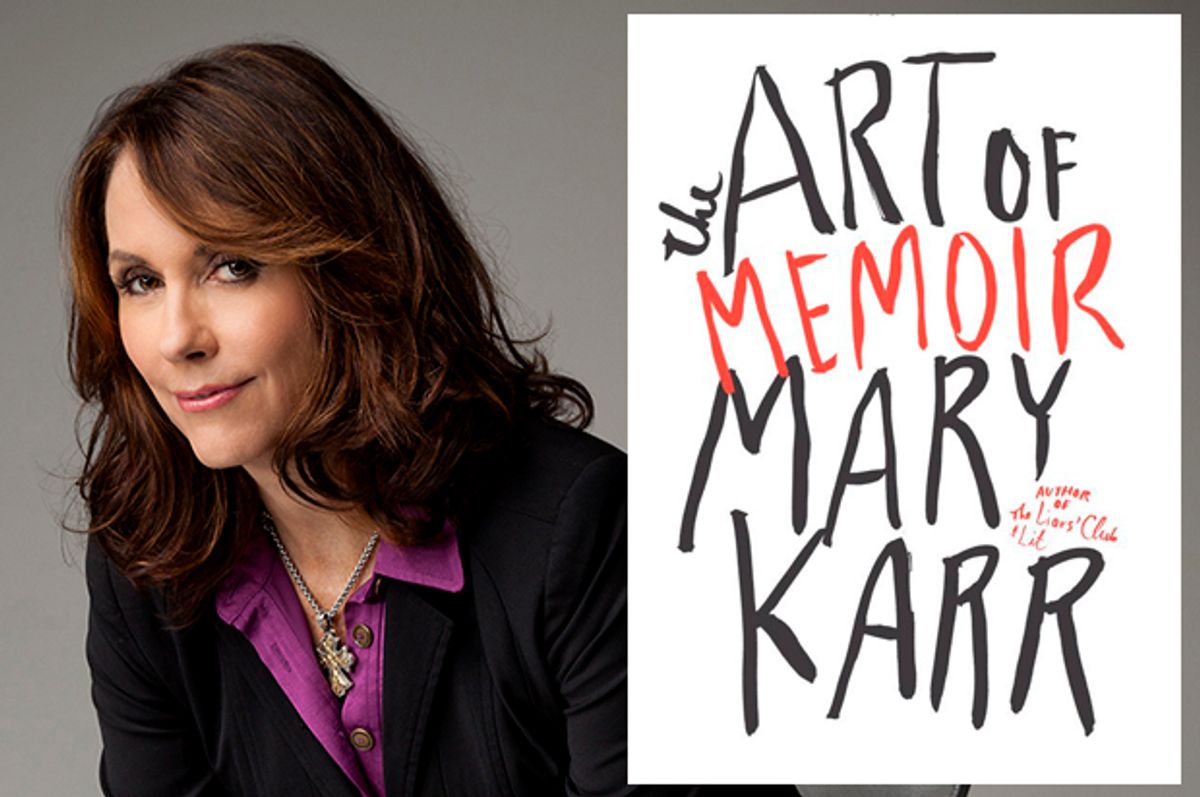

She’s written about her early years, her drinking, a divorce, and her recovery and Catholicism in two other memoirs, “Cherry” and “Lit.” A professor at Syracuse University’s prestigious writing program, Karr has just released “The Art of Memoir,” which is somewhere between a writing instruction book and a defense of the popular but sometimes controversial genre. Cheryl Strayed, whom Karr knew during the “Wild” author’s time at Syracuse, calls the book “astonishingly perceptive, wildly entertaining, and profoundly honest.” (Karr did teach Koren Zailckas, author of "Smashed: Story of Drunken Girlhood.") At the very least, Karr has managed to make a tome about a prose form as ornery as her books about sex, drink and sorrow.

We spoke with Karr in San Francisco, where she was touring behind the book. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Do you think there’s still a bias against the memoir, for being not as serious or substantial as the novel?

I do! Absolutely! When I was in grad school, I think I mentioned Geoffrey Wolff described it as like engraving the Lord’s Prayer on a grain of rice: It’s just a province of loser, outsider weirdos. As though novels aren’t.

But yeah… There’s no danger of the American Academy calling me up to induct me. I’m seen as this low, trashy kind of creature, which is probably not that far from wrong. But certainly the readership for it has ratcheted up, which is a great thing.

Why do you think it’s considered a less serious form?

I don’t think there are any more bad memoirs than there are bad novels: Most novels are bad and most memoirs are bad and most poems are bad and most movies are bad…

I just think genres rise and fall: When the novel began, [authors] were seen as morally reprehensible because it was made up. And [because they didn’t have] any interest in truth. Obviously you can tell great truths in a novel or you can lie in a novel. It’s like photography, which was seen as not an art until the latter half of the last century. That began to change.

But [memoir] is filling a need of dealing with the real. As novels have gotten less real, our readership has grown.

These days, we associate the memoir with pain or trauma or difficult childhood --

Isn’t that what all art is about? Isn’t all art about drama? I think there’s something about it being personal… A novel is seen as grander… Or that you could write a novel and your character and your values would not be on display, as they are in a memoir. Or that reality doesn’t inform a novel. As I’ve said, the best parts of David Foster Wallace’s fiction are nonfiction.

Is a memoir a substitute for therapy? Does writing one help or help with the wound that sometime motivates it?

I had a therapist ask me last night… I think therapy should be a requisite for everybody anyway. I had such a difficult childhood, I don’t know what a normal person, occupying a normal body, would feel like. For me, I had to be in therapy for 15 years before I could even start trying to write the story. In therapy, you pay them; in a memoir, hopefully, they pay you.

I think it is true that writing a memoir is cathartic. But unless it’s cathartic for the reader, don’t publish it… It’s a bomb that doesn’t go off until the reader starts reading it.

The other debate around the memoir is the role of reality and truth – how far is too far for embellishing details. How do you come down on this? You and other writers have been criticized for how you call it.

I actually haven’t been criticized --

I’m talking about the Janet Maslin review.

She made a mistake. I wrote her an email and said, You misread this.

There’s a big difference between accidentally misremembering a small detail, and making up an event that didn’t happen. And if you’re doing something to trick or deceive people, you know when you’re doing that: It isn’t hard to figure out.

Greg Mortenson [author of “Three Cups of Tea” and “Stones Into Schools”] didn’t misremember and think he’d been kidnapped by the Taliban: That wasn’t a mistake of memory.

The truth is, the minute you begin to shape a narrative – to tell one story instead of another story – you’re shaping people’s opinions. That’s why I say memoir is not about external fact; it’s internal, psychological, flawed-by-your-experience. And that’s why I think voice is so important.

One reason I stopped using quotes in “Cherry” and “Lit” is I didn’t want it to read like journalism. I didn’t want it to read like objective reportage.

The mistakes that I make are mistakes of interpretation… Elie Wiesel in “Night” – there’s a terrible scene. His father is horribly sick and dying, and he’s calling out his name. And the SS guy comes in and essentially beats the old man to death for making noise. And Wiesel never responded to it. He said, “His last words had been my name, and I never answered.”

But when I looked in subsequent versions of the book, I couldn’t find it, because he had cut it out. He said it was quote-unquote too personal. But he didn’t cut it out because it was too personal, he cut it out because he was ashamed. So I think the bigger problems we face as memoirist is being scrupulous with our own conscience.

It’s one reason I say, unless you’re a worrier and a nail-biter, you just shouldn’t be writing one of these. It’s too easy to deceive yourself.

So Maslin’s not wrong… But there’s a difference between inadvertent mistakes and making things up. I don’t advocate making things up! If you make things up, you deny yourself the truths that come from being really uncomfortable.

Here’s a great writer who never wrote a memoir: David Foster Wallace. He’s become a hero or a martyr or something since his death. You knew him: Have you been surprised how he’s become a pop-culture figure?

He’s a great genius and people love the work and it’s a terrible tragedy to lose a writer of that caliber. The whole St. David thing, to people who knew him (laughs)… it’s a little hard to take.

David was a very troubled guy for most of his life, obviously. He flatlined before he was 21 years old. He was trying to kill himself; I had suicidal ideation, or I was depressed, I never had what he had.

I think it’s a horrible, tragic story.

Do people misremember him now?

People who didn’t know him misremember him. People talk about how obsequiously polite he was. Like when I met him he called me “Miss Karr.”

But it [was] kind of mocking almost, if you knew him. It was so insincere and Eddie Haskell. It was kind of a really… That’s not what he was like. He was snarky and snappish and difficult, you know… He was not that damn careful.

The whole St. David thing, I don’t know. I loved him, it was a great tragedy, but the people who knew him well… He was not long-suffering; he was a pretty angry guy. At least, when I knew him. I believed he had gotten better. I believed his rap, what he told me. Obviously that was not true.

Did you see the movie?

No. As I understand it – I haven’t seen it – the family is dimly horrified.

I don’t want to see it.

Why don’t we close with you picking a memoir you admire, from any historical period, and describing what makes you like it so much?

I think Richard Wright’s “Black Boy”… “Native Son” is a great novel, but for me as a reader, I think “Black Boy” is an even more artful book.

And in some ways, he was the first semi-civilian to have this massive bestseller in the genre. It’s very hard to write with both tenderness and bitterness, and his ability to combine both those things… and to do it in a beautiful literary style, at times lyrical and poetic… And it’s never really mentioned. But I think it’s a great book.

Shares