From the streets of Ferguson to the South Carolina statehouse, the legacy of slavery in the United States has taken on a new urgency in contemporary America. Today, 150 years after the end of the Civil War, so many of slavery’s scars are still visible, particularly in the South. We must also remember America’s all-but-forgotten ties to slavery in a deeper south – Cuba.

Last December, President Obama announced a new era in U.S.-Cuba relations: “America chooses to cut loose the shackles of the past so as to reach for a better future,” he said, “for the Cuban people, for the American people, for our entire hemisphere, and for the world.” These words also hint at a darker history before the Cuban Revolution; before the construction of Cuban casinos, hotels and nightclubs; before even the Spanish-American War. More than 200 years ago, the horrors of Cuban slavery and the slave trade made America possible.

Of the 12.5 million enslaved Africans who were brought to the Americas from 1501 to 1867, approximately 4 percent arrived in North America. Another 7 percent were taken to Cuba to work in what is now recognized as an “agro-industrial graveyard” of sugar and coffee production. Historians use this term for good reason: the life expectancy of enslaved Africans from the time of their arrival in Cuba was often calculated in single digits. These catastrophic mortality rates meant that Cuban slavery depended on the slave trade. Although the U.S. and England banned the slave trade in 1808, fully 85 percent (759,669) of the slaves to be transported to Cuba were brought after the U.S. ban. By this time, Americans had decided that Cuban slavery made good economic sense and were actively intensifying their participation in the regime.

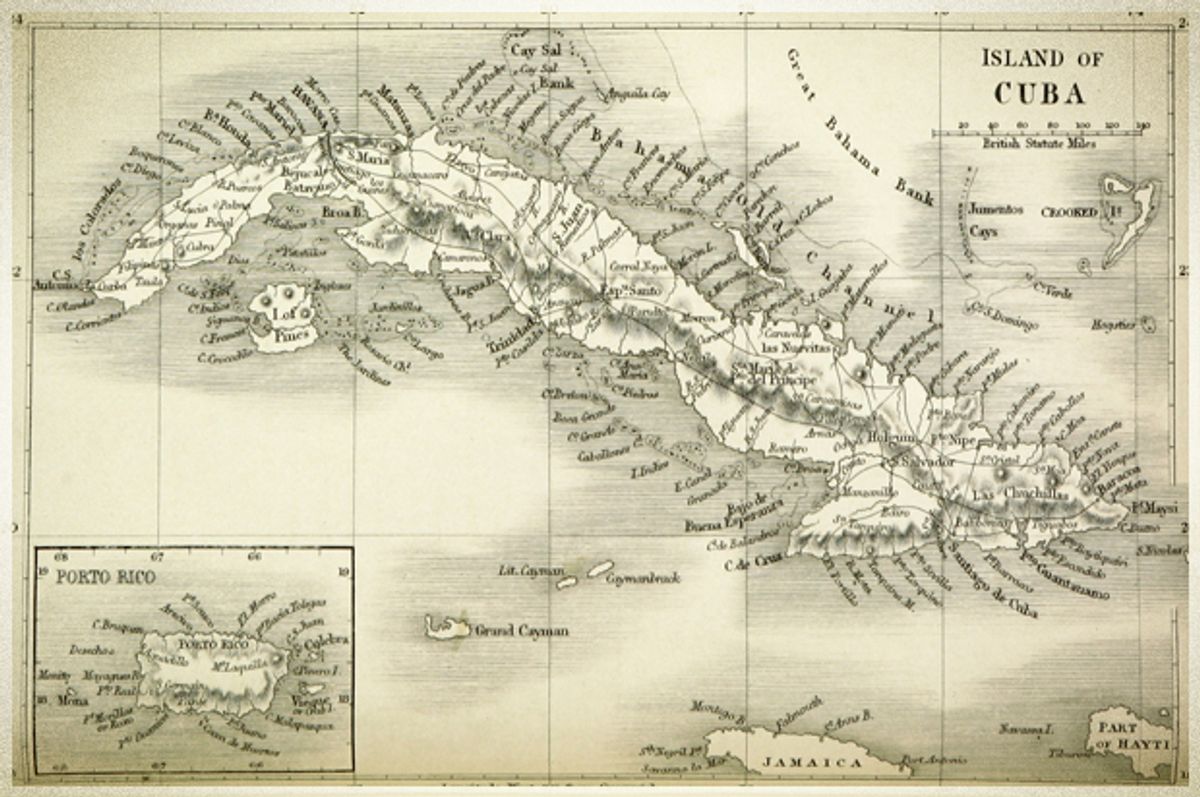

After the American Revolution, the young United States was deeply in debt and on the verge of a rapid expansion of the cotton frontier. But the U.S. merchants who ran the nation’s banks and insurance companies could only provide agricultural loans with a reliable source of specie (gold and silver), and sugar and coffee to back their notes and offset trade deficits with the financial centers of Europe. If coffee, sugar and specie unlocked the doors of European and Asian markets for U.S. investors, slave ships were their key. By the early 1800s, Cuban slavery was at the center of this exchange, and American statesmen, including every U.S. president from Thomas Jefferson to John Quincy Adams, worked doggedly to protect it.

This is why, despite the spread of antislavery sentiment and abolitionism on both sides of the Atlantic, despite numerous laws and treaties passed to curb the slave trade, and despite the dispatch of naval squadrons to patrol the coasts of Africa and the Americas, the slave trade did not end in 1808. In fact, in many later years it intensified, and economic policies of free trade often worked in tandem with the expansion of slavery. The dismantling of trade restrictions – often framed as striking a blow for emancipation – actually strengthened slavery in Cuba and throughout the hemisphere. At every level, Americans made this possible.

In Washington, D.C., U.S. foreign policy protected the expansion of Cuban slavery, most famously with President James Monroe’s declaration in 1823 that, “The American continents … are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.” Known as the Monroe Doctrine, this statement purported to ban Europeans from the hemisphere and would later be heralded as a cornerstone in U.S. diplomacy for generations. At the time of its formulation, however, it was intended to prevent British meddling in the illegal slave trade by Americans with personal interests in the massive expansion of Cuban slavery.

By the 1820s, Cuba had become the second-largest trade partner of the United States and largest sugar producer in the world. American investors, policymakers and merchants – including many from the U.S. North – were involved in every aspect of this development. Some Americans even became expatriate owners and operators of Cuban plantations themselves. In Cuba, a Rhode Islander traded a factory account book for a plantation invoice that listed 103 enslaved men, women and children; a New Yorker forced enslaved Africans to build stone walls around their homes to prevent escape; and a Connecticut merchant, convinced that leniency would trigger revolt, turned his manor into a fortress surrounded by armed guards and dogs. These Northerners had no illusions about Cuban slavery.

Today, this past has been forgotten. Across the United States, museums, monuments and historical sites devoted to slavery have become flashpoints in a national dialogue on issues of race and inequality. Cuba should be a part of this conversation, not only because Cuban slavery and the illegal slave trade helped to create the United States, but also because it is important to remember that this was a choice. In the Early Republic, American leaders made Cuban slavery and the outlawed slave trade a foundation for national development and expansion. This set the stage for a boom in cotton production and decades of interdependent, ultimately fractious economic growth that would trigger the U.S. Civil War. Now, as the U.S.-Cuba rapprochement continues, shining a light on this shared legacy can help both nations begin again.

Shares