Candidate Donald Trump has turned into a much better joke than most people expected. What first appeared like a Simpsons gag, a media stunt, is now leading the Republican field. Trump’s pseudo-populist businessman’s appeal is so surprisingly forthright that, in addition to being the butt of the nation’s laughter, he’s turning the whole political system into a punchline too.

With his careful mix of plainspoken honesty and reactionary delusion, Trump is following an old rhetorical playbook, one defined and employed successfully in the 1936 presidential campaign of Senator Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip. In his campaign’s promotional book "Zero Hour," Windrip laid out the classic nativist call to action that Trump would pick up nearly word-for-word:

My one ambition is to get all Americans to realize that they are, and must continue to be, the greatest Race on the face of this old Earth, and second, to realize that whatever apparent differences there may be among us, in wealth, knowledge, skill, ancestry or strength--though, of course, all this does not apply to people who are racially different from us--we are all brothers, bound together in the great and wonderful bond of National Unity, for which we should all be very glad.

After Windrip’s coup at the Democratic convention, he won a three-way race when the other two candidates split the reasonable vote. Once elected, President Windrip appealed directly to his core constituency of unprosperous and resentful white men to help him repress dissent and bring fascism to America. It’s a chilling historical lesson, even though it didn’t actually happen.

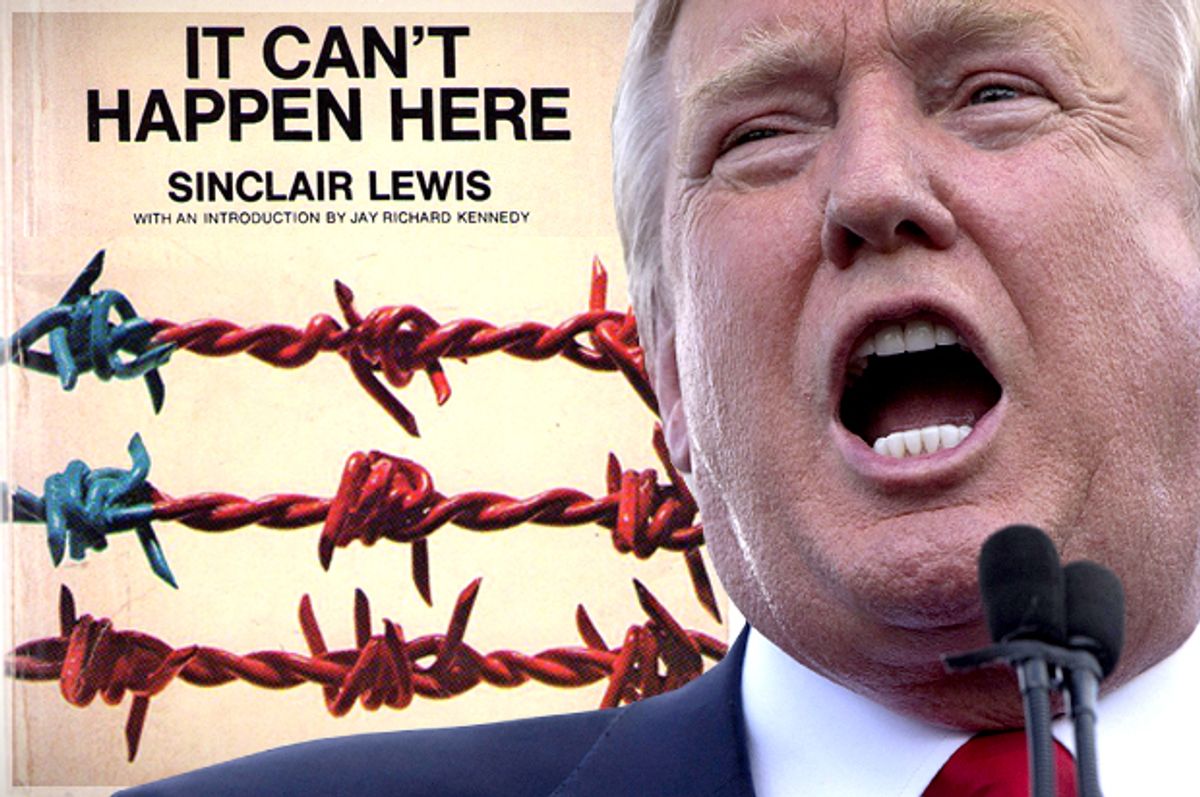

Windrip’s election is the beginning of Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel "It Can’t Happen Here," rather than actual American history. A wonderful example of prophylactic fiction, Lewis used his position as one of the nation’s top novelists to show his countrymen exactly how authoritarianism could rear its head in the land of liberty. The assassination of Louisiana Governor Huey Long (better remembered in literary history for inspiring Robert Penn Warren’s "All The King’s Men") and the reelection of Franklin Roosevelt rendered Lewis’s warning moot for a time, but 80 years later the novel feels frighteningly contemporary.

Like Trump, Windrip uses a lack of tact as a way to distinguish himself. Americans know on some level that the country’s governing system has never conformed to its official values. There are basic contradictions between what politicians and policymakers say and what they do, but also at the core of the national identity. We are, in our own mind, a scrappy underdog and the world’s only superpower at the same time. Right-wing populists don’t shy away from either side of the dichotomy; instead they gain credibility by openly embracing the contradictions. They tell the truth about why they’re lying and declare their ulterior motives.

When it comes to making America great again, Trump promises to wheel-and-deal like the savvy businessman he keeps telling us he is. Instead of just implying their cynicism through participation in the electoral process like a normal politician, Buzz and Trump put it in their “pro” column. “We probably will have to lick those Little Yellow Men some day, to keep them from pinching our vested and rightful interests in China,” Windrip writes of Japan in "Zero Hour," “but don't let that keep us from grabbing off any smart ideas that those cute little beggars have worked out!” Any American president will be a thieving imperialist bastard, but these guys promise voters they will be the best thieving imperialist bastards.

The devil in a devil costume, however, is no less sinister than the besuited version. The social forces that Windrip and Trump invoke aren’t funny, they’re murderous. Our conventional narrative is that the Klu Klux Klan was mocked into nonexistence, but recent demonstrations prove some people still haven’t given up the Lost Cause. That American fascism has always had a goofy Halloweenish quality makes it easier to laugh, but doesn’t protect their targets.

***

As a work of critique, "It Can’t Happen Here" doesn’t stop with populists. The novel’s focal character is Doremus Jessup, a social-democratic newspaper editor in Vermont. Jessup is a member of the exact same political tradition that now animates the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign, which makes Lewis’s story even more apt. If anyone has an ideology to offer beyond the Clinton/Bush status quo and Trump’s extra-cynical embrace of the status quo, it looks to be Sanders and his Vermont-style soft-socialism. But Lewis is not optimistic.

Jessup’s view of Windrip’s election is familiar; it’s what left-wingers are already saying about Trump’s poll numbers. “What I've got to keep remembering is that Windrip is only the lightest cork on the whirlpool. He didn't plot all this thing,” Jessup tells himself, “With all the justified discontent there is against the smart politicians and the Plush Horses of Plutocracy--oh, if it hadn't been one Windrip, it'd been another. . . . We had it coming, we Respectables. . . . But that isn't going to make us like it!" There’s a kind of masochism to this formulation: If you believe in American democracy, then a tyrant’s election is deserved punishment for the failure of principled people to convince their fellow citizens. The system may be rigged, but not so rigged as to be genuinely illegitimate.

The prevailing view of Trump among his critics sounds a lot like Jessup, even after fascism has been imposed: “The hysteria can't last; be patient, and wait and see, he counseled his readers. It was not that he was afraid of the authorities. He simply did not believe that this comic tyranny could endure.” Still convinced he will, at very least, be able to maintain his own standard of living, Jessup dithers. Even as his son-in-law is extra-judicially executed in Jessup’s backyard, he holds out hope that nothing will be required of him beyond that he continue to perform his professional duties with integrity. He does his best to believe the system’s existing foundations are strong enough to repair themselves.

When Lewis exits Jessup’s mind, the book’s tone changes. As the “corpo” state consolidates, Jessup’s liberalism looks more like a combination of laziness and cowardice than conviction. He doesn’t know where the line is between what he can accept and what he can’t, nor what he’s prepared to do once the line is crossed. “So debated Doremus,” Lewis writes, “like some hundreds of thousands of other craftsmen, teachers, lawyers, what-not, in some dozens of countries under a dictatorship, who were aware enough to resent the tyranny, conscientious enough not to take its bribes cynically, yet not so abnormally courageous as to go willingly to exile or dungeon or chopping-block--particularly when they ‘had wives and families to support.’”

This abnormal courage is the real subject of "It Can’t Can’t Happen Here," and Jessup’s democratic socialism is a symptom of its absence. Before long, and despite his cooperation, Jessup ends up in a prison camp with some revolutionaries who were more mentally prepared. Though his cellmates (a sectarian socialist and a communist) still can’t stop arguing about strategy, neither had been waiting for America to cross a line. They already knew what side they were on.

Plenty things like this happened before Buzz Windrip ever came in, Doremus," insisted [mechanic and popular-front socialist] John Pollikop. “You never thought about them, because they was just routine news, to stick in your paper. Things like the sharecroppers and the Scottsboro boys and the plots of the California wholesalers against the agricultural union and dictatorship in Cuba and the way phony deputies in Kentucky shot striking miners. And believe me, Doremus, the same reactionary crowd that put over those crimes are just the big boys that are chummy with Windrip. And what scares me is that if [reasonable and exiled senator] Walt Trowbridge ever does raise a kinda uprising and kick Buzz out, the same vultures will get awful patriotic and democratic and parliamentarian along with Walt, and sit in on the spoils just the same.

Jessup gains respect for the revolutionaries, their foresight, and their disciplined commitment. Still he joins Senator Trowbridge’s exile movement, which (along with a few more coups and a manufactured war on Mexico) restores liberal American democracy at novel’s end. But Pollikop’s warning undermines the pat conclusion. If the nation’s oligarchs find the form of liberal democracy more convenient, predictable, and stable than authoritarianism, it’s not because they’re high-minded, fair, or willing to sacrifice anything. It’s because the nation’s Doremus Jessups agree every day to accept the procedural trappings of justice, democracy, and freedom in lieu of the real thing, even though they know enough to know better.

Once Jessup has lost the privileges that kept him complacent, his deeply held commitment to nonviolent reform fades quickly. Locked in a cell, deprived of the lifestyle that made his patient compromise comfortable, the scales fall from his eyes. Jailed by the same community leaders with whom he used to politely disagree, Jessup realizes who is truly to blame:

It's my sort, the Responsible Citizens who've felt ourselves superior because we've been well-to-do and what we thought was 'educated,' who brought on the Civil War, the French Revolution, and now the Fascist Dictatorship. . . . It's I who persecuted the Jews and the Negroes. I can blame no Buzz Windrip, but only my own timid soul and drowsy mind. Forgive, O Lord!

Is it too late?

Shares