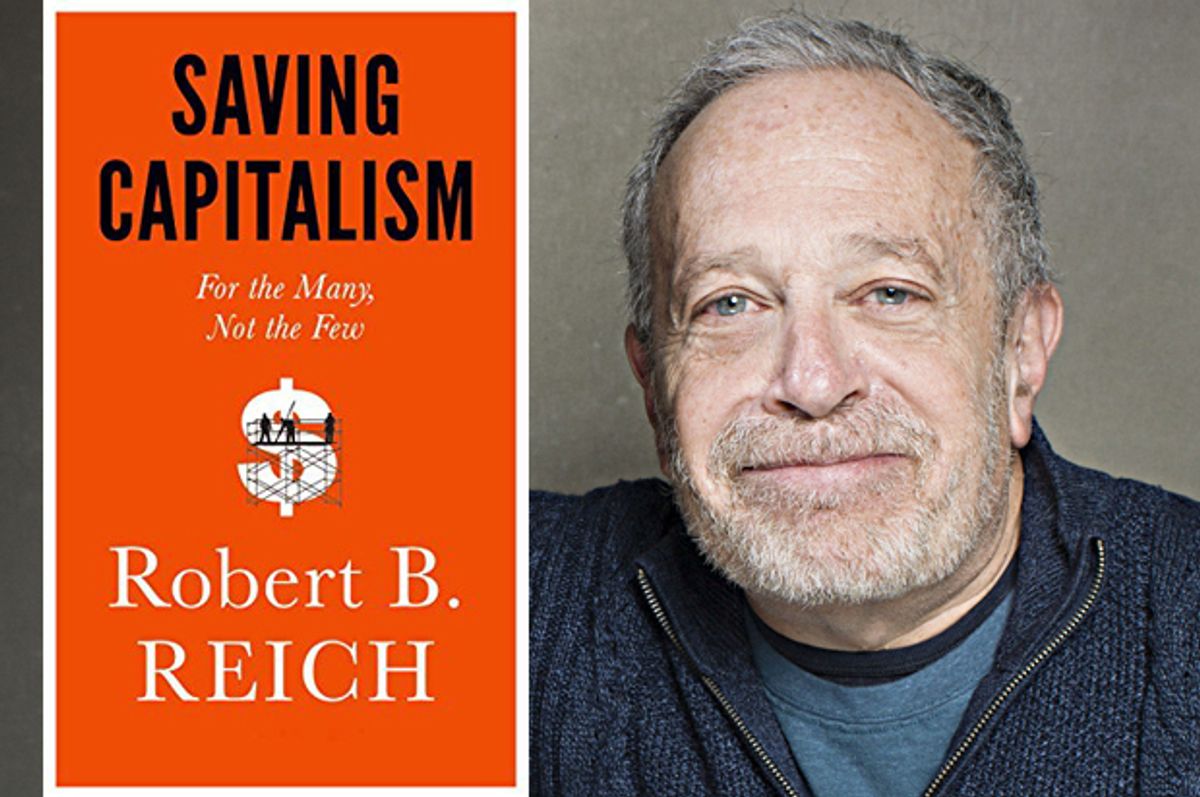

In former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich’s latest book, “Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few,” he tackles a polarizing subject that has long divided liberals and conservatives, and, in recent years, has become increasingly mythological. That subject is the free market, which, as Reich points out in his book, has and will never been free in the sense that so many on the right imagine in their theories.

“Few ideas have more profoundly poisoned the minds of more people than the notion of a ‘free market’ existing somewhere in the universe, into which government ‘intrudes,’” Reich writes, “But the prevailing view, as well as the debate it has spawned, is utterly false. There can be no ‘free market’ without government... Competition in the wild is a contest for survival in which the largest and strongest typically win. Civilization, by contrast, is defined by rules; rules create markets, and governments generate the rules.”

Laws and regulations, whether relating to patents and property or bankruptcy and contracts, help form a stable capitalist market, while a truly “free” market would be akin to the wild (i.e. Social Darwinism). Reich argues that the major problem with the market of today is not that the government has intruded too much, as Republicans generally contend, but that the laws and regulations necessary for a market are tilted in the favor of wealthy individuals and corporations who can buy influence in the political world, rather than average people, i.e “the many,” who cannot. In other words, the free market vs. government debate is largely a pointless distraction from what should be the real debate: Does the market and the rules that establish it work for everyone, or just the few at top who are wealthy enough to shape those rules?

In the United States, the latter seems to be the case. One of the many examples of our unfair economy that Reich points to is America’s bankruptcy laws, which favor wealthy individuals like, erm, Donald Trump, over poor debt-ridden students or homeowners raising a family. As Reich writes of the housing crisis, “The real burden of Wall Street’s near meltdown fell on homeowners... Yet 13 of the bankruptcy code (whose drafting was largely the work of the financial industry) prevents homeowners from declaring bankruptcy on mortgage loans for their primary residence.” As for student loans, filing bankruptcy is quite difficult in the United States, as they are treated differently from other forms of unsecured debt, e.g. medical bills, credit card debt, personal loans, etc. To file for bankruptcy for student loans, one must file a seperate lawsuit, which All Law describes as being “a steep obstacle to overcome.”

The list goes on. Intellectual property laws, for example, have become more generous to corporations over the years, providing lengthy monopolies on sometimes crucial products, like important drugs, and making them less affordable. The massive Trans-Pacific Partnership, like previous trade deals, exposes the length that the American government will go to to protects its corporations. Leaked documents show that the TPP would provide U.S. pharmaceutical companies with extraordinary patent protections and easy extensions around the world (the TPP includes 40 percent of global GDP), which would hit poorer nations like Vietnam the hardest.

One particular sector that has become increasingly monopolistic, Reich warns, is Silicon Valley, thanks largely to these intellectual property laws. Corporations like Google, Apple, and Facebook have armies of litigators that constantly battle over patents that provide them with monopolies on certain products. He writes: “The most valuable intellectual properties are platforms so widely used that everyone else has to use them, too. Think of standard operating systems like Microsoft’s Windows or Google’s Android; Google’s search engine; Amazon’s shopping system; and Facebook’s communication network.” These big tech companies have boosted their spending on lobbying over the years, which may explain why the government has yet to crack down on these massive institutions that largely control entire areas of the internet. In Europe, on the other hand, authorities have started to crack down on this power, and earlier this year, the European Union formerly brought anti-trust charges against Google.

Through political spending and the revolving door, many other sectors, most notably banking, have become increasingly embedded into our political system, which has left our “too big to fail” financial institutions bigger than ever today. The financial crisis fallout, which saw hardly any Wall Street executives face punitive action, reveals the interrelationship between big banks and Washington.

The reality that Reich skillfully paints in “Saving Capitalism” is depressing, but he is optimistic that a populist movement --a nascent version of which can be seen in burgeoning support for Bernie Sanders -- could combat a market that has become entirely favorable towards the wealthiest individuals and established corporations. He argues that certain conservatives and progressives who are increasingly antagonistic to crony-capitalist practices could find ways to unite, as we have seen via their joint opposition to the TPP and corporate welfare.

However, in my view, the problem with this is exactly what Reich points out at the beginning, i.e. the free market vs government debate. Conservatives are the very people convinced that an unfettered free market, where the government simply gets out of the way, is the solution. While these two political factions may unite in opposing certain issues, like the TPP, their solutions are very different.

Reich contends that their is “nothing about capitalism that leads inexorably to mounting economic insecurity and widening inequality.” I’m not so convinced. Capitalism, by definition, is the private ownership of the means of production and distribution. When so few own capital, massive inequality is largely inevitable. True, the government can lessen these inequalities and create market rules that also favor the working class, but this was easier to do in the mid-20th century when capital was less mobile. In today’s globalized economy, a corporation can easily shift operations overseas when the rules of the market become less favorable. A kind of solution would be to create international market rules, which could partly be achieved through trade agreements. Reich advocates requiring trade partners to have minimum wages equal to half of their median wages, which would likely create more customers for American exports and economic stability at home.

In one of the most important chapters in the book, “Reinventing the Corporation,” Reich discusses how a return to “stakeholder capitalism,” along with the spread of capital ownership (i.e. worker cooperatives) is an important step towards developing an economy that works for everyone. Creating more democratic corporations, where all stakeholders own shares of the company, is not a new idea, and the one presidential candidate who has long advocated worker ownership is Bernie Sanders. Indeed, number three on his “Agenda for America” is to assist in establishing worker co-ops.

Reich puts forth many other solutions, such as establishing a basic minimum income for all Americans after they turn eighteen (a proposal that libertarian icon F.A. Hayek endorsed), cutting patent lengths, eliminating tax loopholes such as carried interest, cracking down on new monopolies, overturning Citizens United, and more. Clearly there are solutions, but will a government full of politicians who are constantly in need of campaign donations embrace them? Time will tell.

Needless to say, “Saving Capitalism” is one Reich’s finest works, and is required reading for anyone who has hope that a capitalist system can indeed work the many, and not just the few.

Shares