Between album jackets for Luna and Eels, his design for books by Japanese cartoonist Yoshihiro Tatsumi, his crisp New Yorker covers, and his poignant graphic novels, Adrian Tomine has established himself as one of the nation’s greatest and most versatile cartoonists. That's despite an understated style that hasn’t changed much since his first issues of the Optic Nerve comic.

A native of Sacramento, educated at Berkeley and now living in Brooklyn, Tomine typically sketches Gen Xers who are a bit out of place in a distinctively serene and beautifully colored cityscape. More than just about any other graphic novelist, his storytelling is deeply inspired by literary short story writers and novelists.

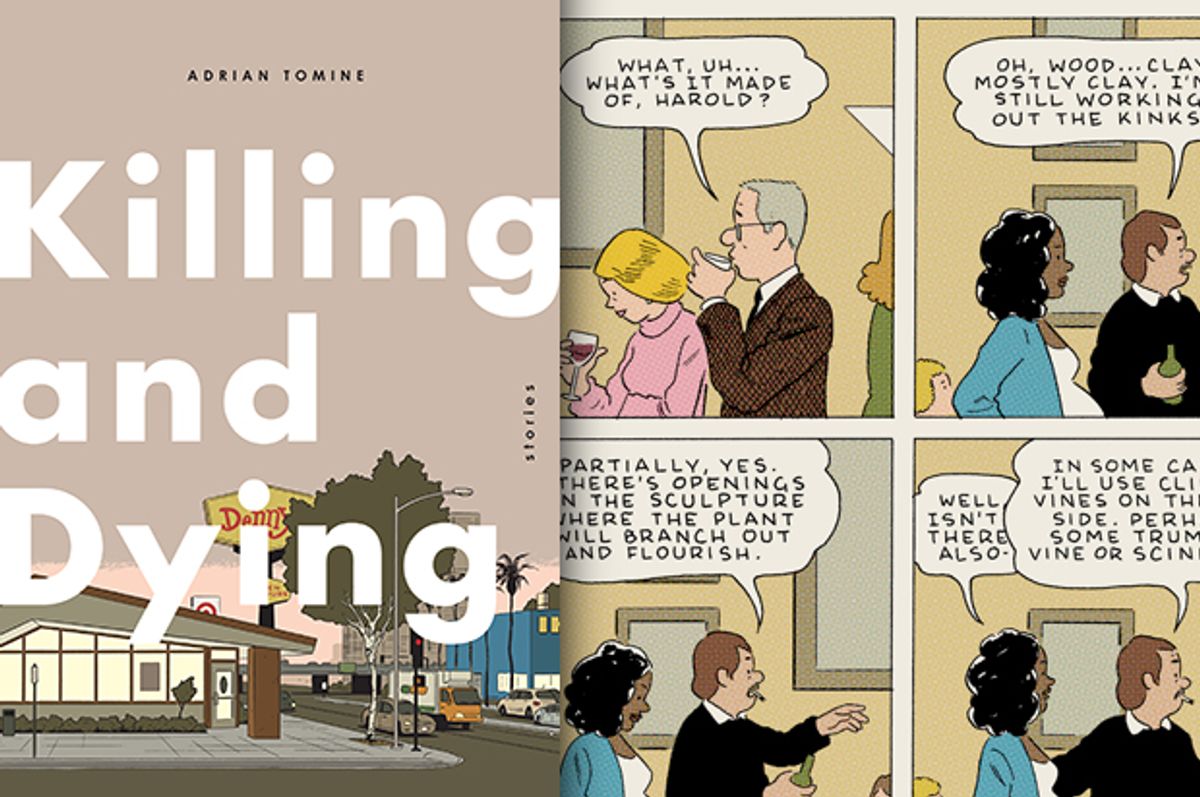

Tomine's latest book, “Killing and Dying,” collects six new stories, each very distinctive from each other, in contrast to the unified style and storyline of his 2007 book, “Shortcomings.”

Novelist Zadie Smith, quoted on the new book’s jacket, describes Tomine as someone who “knows when to use a speech bubble and when silence is enough. He has more ideas in twenty panels than novelists have in a lifetime.”

We spoke to Tomine from his home in New York; the interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

“Killing and Dying”... cheery name for a book, Adrian.

We wanted to find a happy, uplifting title – did some market research, and picked the words that seemed to fit the bill.

Your comics come from several directions, including the work of Dan Clowes, a sort of melancholy or alienated tradition. Each story is a little different, but in general, in spite the beauty of the drawings, this book may be your most bitter yet. Does it feel that way to you?

I’m surprised to hear that. I would maybe meet halfway and say “bittersweet” and say it was the one where I feel like I was kinda being pulled into the two directions the strongest, in terms of humor and jokey stuff and darkness.

I think bitter I would maybe challenge a little bit. This is the book of mine so far that I feel is the least judgmental of humanity, which I don’t always associate with bitterness. I feel like my previous books I was more of a bitter young man standing back with my arms crosses going, “Look at these people.”

I think you’re right. It doesn’t have much of that. You’re now a grown-up and have kids. You’re now 40 or close to it.

Oh no, I’m over 40. I’m 41.

You’re living in New York these days, in a period in which a number of people, most famously David Byrne, have talked about big cities as becoming financially difficult for bohemians, artists, writers, etc. I feel some of that argument in the stories here, like people are being marginalized by urban living. Is that something you see yourself, or that you’re seeing in your posse. Something you’re working through in your stories?

I have no posse in New York, unfortunately. I had a posse in the old West and unfortunately, I haven’t been able to quite replicate that little community of cartoonist friends or anything.

I think part of it is because of what you’re saying. New York is a brutally expensive place to live and the kind of person who might have the dedication and esoteric taste to make the comics that I would really love is finding it more relaxing to live elsewhere.

I’ve never quite had the experience of living in such a high expense, high-pressure atmosphere, especially in the neighborhood of Brooklyn that I’m in. It’s just a really interesting experience because on one hand, it alienates certain people and pushes out people who I wish I could be friends with, and it also attracts people that I normally wouldn’t spend time with. In order to survive in New York, you have to [either] come from money [or] really be working at the top of your game. That’s kind of fun. For me, it’s a fun experience. I’m sitting bored at a playground and I’m supposed to interact with another parent but it turns out they’re an editor at the New York Times Book Review or something like that. You just never know who you’re going to encounter on a regular basis.

But yeah, it’s tough. I wouldn’t be here if I was at an earlier stage in my career. I would have just packed up my bags and bailed.

There’s something about the amount of detail in what you do that makes me feel like you must really know these people in your stories. I don’t really feel that way often about a writer or an artist.

You’ve got a comic called "Amber Sweet" about a woman in the San Fernando Valley who is mistaken for a porn star. You’ve also got a title piece — "Killing and Dying" — which is mostly about an alienated teenage girl who wants to become a stand-up comedian. There’s so much psychological detail that you must have known somebody like these people — or does it just come out of your head?

I appreciate that you put your question in that way because it puts a positive spin on what’s becoming a recurring theme of interviews talking about these books. To me, the negative spin on it is the strong interest on decoding stories and finding the one correlation between my real life and the fiction. It seems to be like an obsession and it feels like a compliment now, the way you phrase it. I appreciate that.

I think that somehow I’ve arrived at this way of writing that is both, in some ways, the most made-up, fictional, invented work that I’ve ever done and also, somehow the most personal. So, I think a lot of maybe what’s going on is the physical details or the mechanics of the settings of the story are fabricated. And, just the fact that it’s a one-man process in creating the whole book, from writing to drawing and designing, it’s inevitable that my experience, my thoughts and personality just seeps into the work.

There’s definitely a lot of choices where you can’t be vague in a way a prose writer can say, “Oh! They went to a restaurant.” I have to draw it, and I usually have this choice of: Do I just fake it and make it a generic restaurant, or do I kind of envision where this family really would go to celebrate, do some research what the inside of a Cheesecake Factory restaurant might look like? There’s just a ton of nearly invisible work that goes into these stories. It’s nice when someone picks up on it and it’s okay if people don’t.

So it sounds like you really did what a fiction writer does. You really did make these people up. This is not somebody you were friends with or knew about. From your earliest stuff, you’ve been interested in short story writers and novelists. I remember you talking about Tobias Wolff and Raymond Carver and so on. Who are you reading and thinking about these days? Is it the same people, or do you have other writers who are inspiring you these days?

You know, what's interesting is right now I feel like I’m back at college because I’m about to embark on this book tour now. And somehow, at almost every event, I’m paired up with this interesting author, who in some cases I might need to get caught up on their work or don’t know the full breadth of their career or something. So basically, I have a giant stack of books here and every night, I try to read as much as I can so I don’t look like an idiot in front of these [writers] who agreed to sit down with me. Basically, I’m trying to be caught up with the people that I’m having events with on this tour. Beyond that, I haven’t had a lot of time for pleasure reading; just kind of wandering into a bookstore and picking something up on my own.

There’s nobody who’s become a major influence, say the way Carver used to be?

I think the last person who I really read everything of was Philip Roth, and that might have come through a little bit when I was working on “Shortcomings.” When I have the free time to read whatever I want, I move simultaneously in two directions. I might look at what’s new and say, "[Rachel Kushner's] 'The Flame-Throwers,' every body’s talking about that, so…” And also, maybe there’s some weird John Cheever book that I never got around to reading.

I feel like I went so deep down the path of gritty realism. I read all the Carver and even got the sort of out-of-print books of Andre Dubus, Richard Yates and all those guys. I love those guys and I think that’s going to be my baseline of interest. Lately I’ve just been stumbling upon books and I’ve just been impressed by this idea of plot and “Flame-Throwers” is a good example; you just get sucked in by the plot. Same thing with ‘The Circle" by [Dave] Eggers; it almost feel like a commercial thriller as a Trojan horse for all kinds of weird ideas. It wouldn’t be palatable for him just saying, “This is what I think of the Internet.” I think that’s fascinating. I love the idea of trying to do the work of old-fashioned novelists of plotting, and of really making you curious about what’s going to happen next and all that, but also trying to load it up with your weird thoughts and opinions.

Since your first book, I guess 1998 was “Sleepwalk,” right? The Internet existed but its real impact came later. I wonder how much it’s reshaped what you do and the work of other graphic novelists and cartoonists?

Hugely. I think this happens to all people and suddenly, I woke up and I was kind of like the old guard, I was kind of like the old fuddy duddy. I was still getting uptight if I saw someone reprinting some my images online, without giving me credit and the young hip people are like, “Sorry that’s Tumblr, that’s just the way it is.” And I’m like, oh okay, I didn’t realize at all that everything had changed.

I’m adjusted to it. In a way, for me it was the sort of change that I had to make in my brain was not, “Do I prefer the old world versus the new world?” It was sort of like, “This is the new world and I have to deal with it.”

For a long time, I was very resistant to the idea of online publication or even e-books or something like that. There was a time that I felt like you could choose a side and I know which side I’m on. And then suddenly, I look and all my stuff is being scanned and being put up on the Internet anyway, for free. So, I can either go along for the ride or not, but I’m not going to control the situation.

You used to hand draw everything.

I still do, yeah.

Still an extremely slow way to go. Has your working method changed at all in the last decade or so?

It has but not in a more digital way. This book, “Killing and Dying,” to me was a total reaction to the process of making “Shortcomings,” where I was locked into a single way of drawing and writing and everything for a long. I basically started getting sick of it and feeling kinda trapped by it.

Well, each of these stories has a different visual sensibility, is that what you mean?

Yeah, by design, not just visually, but the process of writing the stories. Just every little thing I tried to think of. Like what’s some weird way of doing it that I haven’t done before? “Killing and Dying,” that story, is drawn all in pencil. There’s no ink involved in it. It was drawn on sheets of typing paper and each panel was on a separate sheet of typing paper and I sort of assembled it all later. Which was great because I stacked them all on top of each other and traced the background, and I’d just draw a new figure on top of it – almost like animation. There was a lot of repeated backgrounds and compositions throughout the story, and it made it much easier if it was made on transparent paper. Stuff like that, most people will pick up on a subliminal level but if it’s something I had to do for myself to avoid that feeling of drudgery, which I think is a terrible thing to come through in the work.

The last one in the book, called “Intruders,” has no color at all. It’s all black and white and a kind of beige. How did you do that one?

That was a bit of a throwback. It’s funny because it’s a story of a guy [who breaks into an apartment] trying to get back into his old life, and in way it was also me trying to get back into the old experience of making comics. The process and the feeling that I had of making comics, back when I was doing mini-comics and it sort of connects visually back to the old Optic Nerves in way. And, that was fun, it was nice to work small and not be too fussy about the line quality and allow myself to use narration again, which I completely cut out for “Shortcomings.” It just seemed like a good ending to the book to for me, in a lot of ways.

I think people who don’t do this for a living don’t understand how long it takes to do one of these, especially, in an old-school kind of way. Give us a sense of how many hours a day, you typically work and how long it takes.

The basic work schedule for me is whenever I’m not doing anything more important, like taking care of my kids or something. So, it’s most of the day, five days a week, most evenings and sometimes on the weekends. It’d be sort of depressing to really express how slow this process is. When I started working on the book, my oldest daughter was not born yet, and we are just about to celebrate her sixth birthday. I have a younger daughter that has come along in the interim as well.

Shares