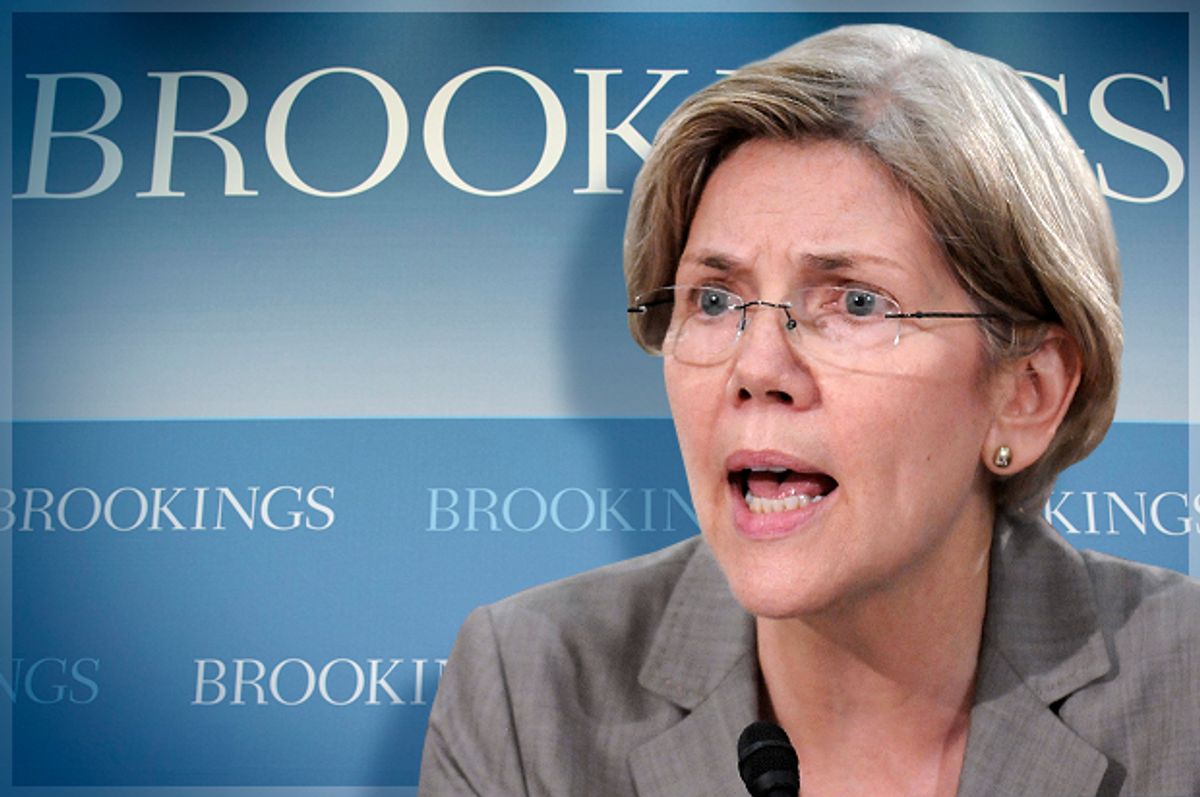

Earlier this month, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., made news targeting Robert Litan, a longtime staffer at the Brookings Institution, with a conflict of interest charge. Litan had co-authored a paper arguing against new financial industry regulations which Warren supported. Warren argued in a letter that industry-funded study was “editorially compromised work on behalf of an industry player seeking a specific conclusion.” After Warren’s letter and subsequent news coverage, Brookings immediately threw Litan under the bus and argued that the study “was not connected with Brookings in any way” and that when Litan “used his Brookings affiliation for congressional testimony he violated a policy that prohibits nonresidents from using their affiliation with Brookings for that purpose.” Litan, undoubtedly sensing his time at Brookings was over, resigned. The fallout in the days since has been entirely predictable. Litan’s defenders — including his co-author, centrist Democratic economists, and the right wing — are declaring a “McCarthyism of the left” and are using the incident as another example of Warren’s leftist ideas overtaking the Democratic establishment. Warren’s defenders are, rightly, pointing out that Litan’s right to speak and produce papers for corporate clients has not been repealed.

Nevertheless, in all of this back-and-forth, the role of Brookings itself has been lost — and we shouldn’t let them off the hook. For quite some time, Brookings has benefitted immensely from its reputation as the most respected think tank in Washington. Despite the fact that the think tank is largely considered “left-leaning,” “center-left” or “Democratic-leaning,” its scholarly integrity is rarely questioned and it is simply not seen as being captive to corporate interests. Quite the contrary, Brookings is often seen in contrast to the Heritage Foundation — a think tank generally assumed to be in the bag for conservative corporate interests. However, as someone who has researched the history of think tanks in the United States, I want to call these common assumptions about Brookings into question. A look at the last four decades of Brookings’ institutional history shows that, far from being free of corporate interests, the Institution has been active in seeking private monies from corporations and others. Moreover, Brookings started soliciting these types of donations largely in response to right-wing think tanks doing the same. In doing so, then, they lost whatever liberal, Democratic institutional character they once had, instead becoming a “balanced,” “bipartisan” think tank.

Despite these changes, Brookings is still regarded as the ideological opposite of Heritage. As the two poles in Washington’s think tank ecosystem, such a dynamic has drastically shifted the overall plane of public policy debates to the right over the past forty years — with a hard-right Heritage Foundation “balancing” a bipartisan think tank funded very often by the same corporate dollars. Brookings might be trying to throw Litan under the bus now, but Litan and his research fit comfortably at home within Brookings as it has established itself over the past 40 years.

Although the Brookings Institution was founded in the teens and 1920s, it didn’t acquire its reputation as being reliably of a liberal, Democratic character until after World War II. In the 1950s, under a new president, the think tank firmly situated itself within a technocratic consensus of policymaking at the time. Under such a consensus, social scientists and other experts were thought capable of defining social problems and then coming up with solutions to those problems. Such a consensus was more at home in the Democratic Party of the fifties, even though many Republicans accepted it as well. By the end of the Eisenhower administration in 1960, Brookings had so thoroughly positioned itself at the center of this consensus that it was the go-to institution for experts in both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations from 1961 to 1968. This involvement in the federal government led President Johnson, in 1966 at Brooking’s fiftieth anniversary, to declare “you are a national institution, so important to, at least, the Executive branch — and I think the Congress and the country — that if you did not exist we would have to ask someone to create you.” By the late sixties, then, Brookings was thought of as a reliable liberal policymaking think tank most associated with the Democratic Party. However, because such policymaking was also, at some level, thought of as scientific, empirical and in the realm of “the experts,” Brookings maintained and solidified its reputation as scholarly and detached.

As the sixties turned into the seventies, Brookings began its move away from this liberal, Democratic, technocratic orientation. It did so largely as a result of a sustained assault on its reputation by conservatives — those in the Nixon administration and others in conservative think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Heritage Foundation. Although discussions in the Nixon White House regarding breaking into and firebombing Brookings are now the most famous in this regard, in the long-term it was actually conservative think tanks that were more effective in undermining Brookings’ liberalism.

Whereas Nixon and his advisers saw Brookings primarily as a political enemy to be demolished by any means necessary, Bill Baroody, president of AEI, saw it as a place which could be used to increase the power, prestige and finances of his own institution. Baroody did this by positioning AEI as the necessary “balance” to Brookings in a so-called “marketplace of ideas.” If Brookings was hopelessly liberal, then AEI would be staunchly conservative.

Such a counterpositioning had two effects. First, as I’ve argued before, it allowed AEI — and soon other think tanks like Heritage — into public policy debates by virtue of their conservatism, not necessarily whether they were presenting workable ideas. Secondly, such a counterpositioning was an excellent way for Baroody to raise money from the conservative elite in the 1970s. When raising cash, Baroody effectively positioned corporate and wealthy interests, and by extension AEI, as fundamentally powerless — as the “little guys” struggling to make their voices heard above that of the all-powerful Brookings. For instance, when writing to prospective donors, Baroody often cited the comparative finances of the think tanks, noting that “compared to other institutions in the public policy research area, the total resources available to AEI have been modest. Its annual budget is perhaps one seventh that of the Brookings Institution.”

In another memo to prospective donors, AEI argued that Brookings used these vast tax-exempt resources to launch an “assault on the political, economic and social structure of the country.” The founders of the Heritage Foundation used similar rhetoric in describing why their new think tank was needed. In a 1974 memo, Heritage’s founders argued that Brookings “had a disproportionate influence upon policy decisions at the Federal level in that influence has been consistently liberal-socialist in its viewpoint. Drawing the bulk of the funding from the corporate giants of industry, this is been a case of the viper of socialism in the bosom of the free enterprise system.” Such rhetoric played on the fears of wealthy conservatives and urged them to get involved in “competition of ideas” by funding AEI and Heritage.

Brookings’s response to these charges of liberal bias and to conservatives raising corporate cash started the trends of the Institution that we see today: it began to raise its own corporate cash while at the same time moving away from its liberal institutional character and to a “bipartisan” one. Such shifts were as much a response to the charges and actions of conservative think tanks as they were due to the new financial realities of the United States in the 1970s, which eroded the Bookings endowment from $49 million to $33 million in that decade. After this setback, the board of trustees at Brookings desired a new president who could find new sources of income. The board wanted such new sources to include corporate support. However, by this point, conservative think tanks had done much to tar Brookings as fundamentally biased against corporate interests.

Given this fact, Brookings wanted a new president in 1977, someone who would signal that such a perceived bias was not true. The man they hired for the job was Bruce K. MacLaury, an economist who served two years in Nixon’s Treasury Department. While financial concerns contributed to MacLaury’s hire, it was also clear that Brookings trustees did not want to be viewed as a liberal Democratic institution any longer and were particularly concerned with conservative critiques which said that they were. MacLaury’s arrival signaled that the trustees were now willing to address such concerns with a new president who would hire more conservatives.

Mainstream media outlets covered, and in many cases, lampooned, the Brookings shift. The Los Angeles Times ran a fake “help wanted” ad which read: “Republican. Deep thinkers with high level experience in government, economics, foreign affairs. White House background helpful. Apply Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.” The Times writer then noted, “Dignified Brookings isn’t about to do anything as crude as place a want ad. But the fact is that the renowned think tank, which many regard as a citadel of liberal Democratic ideas, has a new president, Bruce K. MacLaury, who wants to recruit some prominent Republican scholars. MacLaury hopes to obtain for Brookings a more balanced ideological image and, in the process, to obtain more financial contributions from the corporate world.”

Joking aside, it is hard to understate the significance of this move and the success it represented for conservatives in think tanks and elsewhere. By critiquing Brookings as liberally biased, conservatives provoked a reaction which benefitted conservatism greatly. Rather than become more forthrightly liberal, Brookings was balancing its own institution ideologically — what MacLaury described to one publication as the need to have “a diversity of views to keep the place credible.” Another Brookings official hired on by MacLaury went even further declaring that the research at the institution should no longer be thought of as liberal or nonpartisan given that “at best research can only be bipartisan.”

Such a dynamic continued from the late seventies to the present. In the 1980s, the think tank world was dominated by the rise of the Heritage Foundation with its rapid response policy publications which very often put aside any pretense of scholarly research. Although Brookings was still seen as the most prestigious of all think tanks, and still had the largest budget and endowment, there was enormous concern that that it was losing relevance to the new think tank model Heritage represented. A December 1983 New York Times report reflected such concerns and the changes this brought about at Brookings — changes which further pulled Brookings to the right in its institutional identity. According to the report, in order to keep up with places like Heritage, there was a “very overt fashion change” in the “character of [Brookings'] product.” What this meant was that there was “less a disposition to produce complete analyses in book form, and a more pronounced disposition to comment in either testimony, short form or very brief monographic form.”

Such short-form work even had names which aped Heritage publications: “Brookings Review," "Brookings Discussion Papers," and the handsomely published "Brookings Dialogues on Public Policy.” Additionally, Brookings hired a full-time public relations director and invited journalists to regular briefings in order to make sure Brookings was receiving the kind of publicity that Heritage was. Such changes were unsurprising given that they came about under MacLaury, who would have had less problems with conforming to the models of conservative think tanks and publishing papers which were less scholarly and rigorous. Moreover, by the mid-eighties, Brookings had hired on many Republicans who would not have taken issue with this new turn and who obviously continued to pull the institution away from its liberal Democratic identity.

Such shifts continued to the end of MacLaury’s tenure as president in 1995 and long after that. However, despite these long term trends towards a bipartisan institutional character and solicitation of private corporate donations, Brookings continues to be largely thought of as something it no longer is: left-leaning and free from corporate taint. Recent news reports have damaged the idea that Brookings is free from private influence over scholarship, but the idea of Brookings as a left-leaning institution still persists — a idea which Litan’s resignation seems to provide evidence for. However, nothing could be further from the truth.

The movement of Brookings over the last 40 years from liberal to bipartisan has shifted the entire American political spectrum, given that it occurred in response to conservative think tanks becoming more ideologically hard right. While Brookings is still often thought of as liberal, a true liberal or left position often gets shut out of the debate entirely with the debatable political spectrum only ranging from the Heritage Foundation’s Tea Party conservatism to Brookings’s mushy bipartisanship. To the extent that those like Elizabeth Warren can show there is something outside of this narrow spectrum, the better off we’ll all be.

Shares