Conservative scholar Robert George has issued a “call to action” to constitutional scholars and presidential candidates who are opposed to the Supreme Court’s gay marriage decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. George believes the decision was wrongly decided, that it is a gross usurpation of judicial power and misinterpretation of the Constitution.

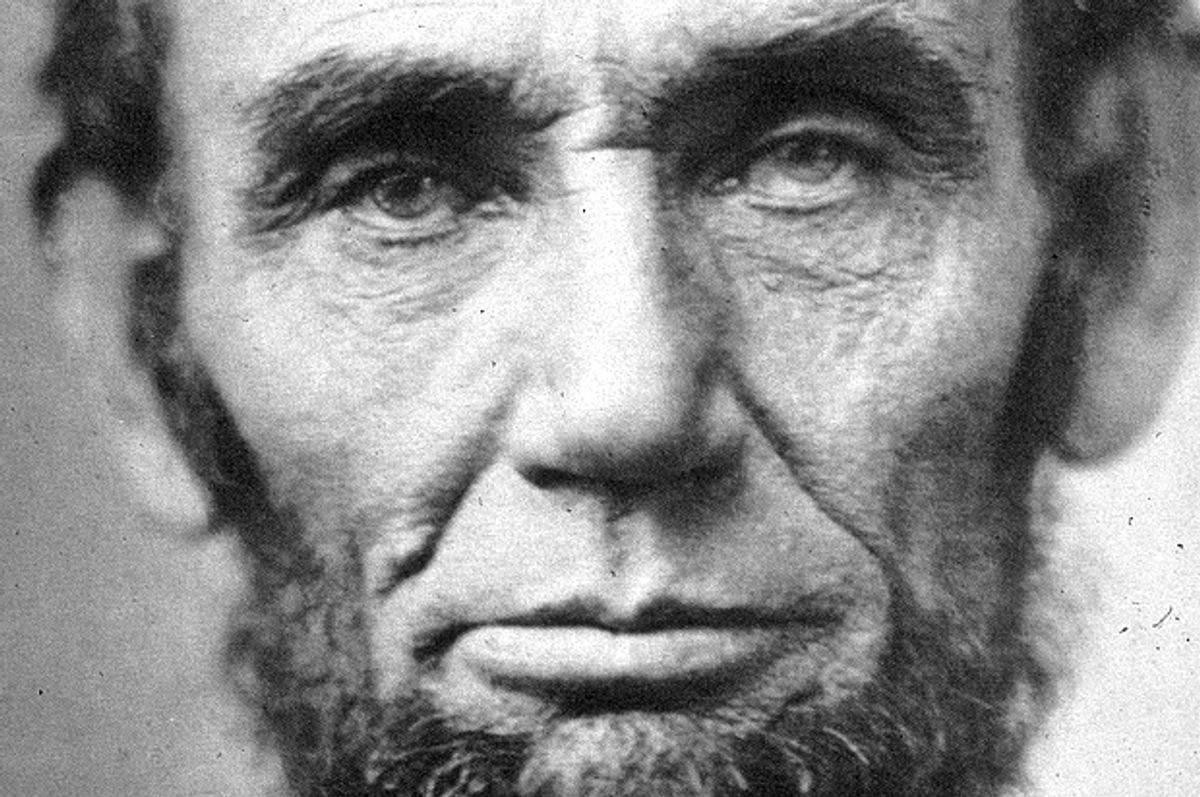

But things take an interesting turn in the statement, when George invokes Lincoln on Dred Scott to argue that, despite the Court’s ruling, we—and more important, government officials, including future presidents—should not accept Obergefell as the law of the land. That is, we, and they, should not accept Obergefell as binding on our/their conduct:

Obergefell is not “the law of the land.” It has no more claim to that status than Dred Scott v. Sandford had when President Abraham Lincoln condemned that pro-slavery decision as an offense against the very Constitution that the Supreme Court justices responsible for that atrocious ruling purported to be upholding.

Lincoln warned that for the people and their elected leaders to treat unconstitutional decisions of the Supreme Court as creating a binding rule on anyone other than the parties to the particular case would be for “the people to cease to be their own rulers, having effectively abandoned their government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”

Because we stand with President Lincoln against judicial despotism, we also stand with these distinguished legal scholars who are calling on officeholders to reject Obergefell as an unconstitutional effort to usurp the authority vested by the Constitution in the people and their representatives….

As the 2016 election season heats up, we call on all who aspire to be our next President to pledge to

- treat Obergefell, not as “the law of the land,” but rather (to once again quote Justice Alito) as “an abuse of judicial power”

- refuse to recognize Obergefell as creating a binding rule controlling other cases or their own conduct as President…

Like Lincoln, we will not accept judicial edicts that undermine the sovereignty of the people, the Rule of Law, and the supremacy of the Constitution. We will resist them by every peaceful and honorable means. We will not be bullied into acquiescence or silence. We will fight for the Constitution and our beloved Nation.

This move is interesting for two reasons.

First, it’s always interesting to me when conservatives depart from their customary role as the defenders of the law and lawfulness, and take up the more lawless elements of what I think is their true patrimony. Here’s how George finesses that issue:

We have great respect for judges. We have even greater respect for law. When judges behave lawlessly, it is the law that must be honored, not lawless judges.

The Supreme Court is supreme in the federal judicial system. But the justices are not supreme over the other branches of government. And they are certainly not supreme over the Constitution.

In Obergefell v. Hodges, five justices, without the slightest warrant in the text, logic, structure, or historical understanding of the Constitution presumed to declare unconstitutional the marriage laws of states that maintain the historic and sound understanding of marriage as the conjugal union of husband and wife.

But, second, and perhaps more interesting, is how George uses, or misuses, Lincoln.

It’s certainly true that Lincoln was opposed, strongly opposed, to the notorious Dred Scott decision. It’s also true that Lincoln refused to treat that decision as constitutional precedent. But Lincoln was equally of the mind that he and other officials could not resist the decision. Here’s Lincoln’s famous speech on the case in 1857:

We believe, as much as Judge [Stephen] Douglas, (perhaps more) in obedience to, and respect for the judicial department of government. We think its decisions on Constitutional questions, when fully settled, should control, not only the particular cases decided, but the general policy of the country, subject to be disturbed only by amendments of the Constitution as provided in that instrument itself. More than this would be revolution. But we think the Dred Scott decision is erroneous. We know the court that made it, has often over-ruled its own decisions, and we shall do what we can to have it to over-rule this. We offer no resistance to it.

Lincoln is careful to say that in not treating Dred Scott as precedent he means that he will seek to overturn the decision by the Court itself, that he will not allow to be viewed as settled law. He will agitate for the wrongness of the decision, argue against its application in future rulings, and perhaps seek the appointment, if/when given the chance, of Supreme Court justices who agree with him. What he will not do is resist the decision.

Again, Lincoln:

He [Douglas] denounces all who question the correctness of that decision, as offering violent resistance to it. But who resists it? Who has, in spite of the decision, declared Dred Scott free, and resisted the authority of his master over him?

Lincoln draws a clear distinction between questioning the correctness of a decision and resisting that decision, acting in defiance of it. It’s true that he’s only referring to the specifics of the case (a qualification George makes much of: “a binding rule on anyone other than the parties to the particular case”), but in his First Inaugural, which George quotes (actually misquotes, albeit in a minor way*), Lincoln extends the distinction behind the specifics of the case.

I do not forget the position assumed by some that constitutional questions are to be decided by the Supreme Court, nor do I deny that such decisions must be binding in any case upon the parties to a suit as to the object of that suit, while they are also entitled to very high respect and consideration in all parallel cases by all other departments of the Government. And while it is obviously possible that such decision may be erroneous in any given case, still the evil effect following it, being limited to that particular case, with the chance that it may be overruled and never become a precedent for other cases, can better be borne than could the evils of a different practice. At the same time, the candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal. Nor is there in this view any assault upon the court or the judges. It is a duty from which they may not shrink to decide cases properly brought before them, and it is no fault of theirs if others seek to turn their decisions to political purposes.

Again, while Lincoln insists that there is a role for the people and their representatives to engage in constitutional politics, to argue for their preferred interpretations of the Constitution and what it requires (to that extent, George is correct), perhaps to contest the ruling at its perimeter, and while he also insists that he will do all that he can to ensure that Dred Scott will not become precedent, there’s little in these statements on Dred Scott to suggest that Lincoln believes government officials have it within their rights to “refuse to recognize” a Court decision as “creating a binding rule controlling…their own conduct.”

Lincoln scholar John Burt provides a sensitive summation of Lincoln’s position on Dred Scott in a 2009 article from American Literary History.

In his Springfield speech of 26 June 1857 on the Dred Scott decision, Lincoln did not adopt the common antislavery ways of countering the decision. He proposed no popular acts of resistance, he did not propose nullifying the decision through the acts of the other branches or the state legislatures, and he did not propose attacking the Court’s power by changing the number of justices. He not only submitted to the decision as regards Dred Scott himself, but also conceded that the case would govern other persons in Scott’s position. Yet he did not concede that he would have to treat the decision as prescribing a political rule for his future course. In other words, he did not feel that as a legislator he was obligated to support further laws that would seem to have been called for in Chief Justice Taney’s opinion, or to pass other laws that would be consistent with that opinion. And he felt that he could still support laws that would challenge the decision at the margins, testing its limits and providing occasions for the Court to rethink its views. Lincoln also proposed pushing a gradual change in the Court’s point of view which would follow from his having political control over the confirmation of new justices over the long term: a Republican Senate could put in motion the reversal of the decision one justice at a time, in a process which might have taken decades to complete.

In fact, Burt provides additional information of how Lincoln attempts to push the boundaries of opposition to their outermost limits without going where George goes in his statement on Obergefell.

In the 1858 Quincy debate with Douglas, Lincoln distinguished between accepting the Dred Scott decision as binding upon poor Scott and adopting that decision as a political rule. Lincoln did not propose to defy the Court in that case, or in any subsequent case similar to it. But he did propose to treat the question it had attempted to close as one that is still open, subject to further legal testing, capable of being eroded around the edges by political challenges, until finally Dred Scott loses its legitimacy, loses the background sense that its conclusions are not only reasonable but inevitable, a sense, it’s fair to say, that the Dred Scott decision never enjoyed in the first place. Lincoln specifies rather precisely what it means to oppose the Dred Scott decision:

We oppose the Dred Scott decision in a certain way, upon which I ought perhaps to address you a few words. We do not propose that when Dred Scott has been decided to be a slave by the court, we, as a mob, will decide him to be free. We do not propose that, when any other one, or one thousand, shall be decided by that court to be slaves, we will in any violent way disturb the rights of property thus settled, but we nevertheless do oppose that decision as a political rule, which shall be binding on the voter to vote for nobody who thinks it wrong, which shall be binding on the members of Congress or the President to favor no measure that does not actually concur with the principles of that decision. We do not propose to be bound by it as a political rule in that way, because we think it lays the foundation not merely of enlarging and spreading out what we consider an evil, but it lays the foundation for spreading that evil into the States themselves. We propose so resisting it as to have it reversed if we can, and a new judicial rule established upon this subject.

George is not terribly clear as to what he means when he writes that presidential candidates should pledge to “refuse to recognize Obergefell as creating a binding rule controlling other cases or their own conduct as President.”

What does seem clear is that Lincoln’s strongest phrasing of opposition—that he opposes the “decision as a political rule,” meaning among other things that he refuses to accept the notion that he must “favor no measure that does not actually concur with the principles of that decision”—is miles more modulated than “refuse to recognize Obergefell as creating a binding rule.” After all, one can support many laws that depart from the principles of a decision without violating that decision. Part of what Supreme Court decisions are often about, after all, is whether some law or act of government is in fact a violation of the principles the Court has enunciated. What is or is not in keeping with the principles of a decision is a contested question. And even then, a law or act of government could lie outside the principles enunciated by the Court and still not violate the Court’s decision.

But when George calls in his statement for candidates who “support the First Amendment Defense Act to protect the conscience and free speech rights of those who hold fast to the conjugal understanding of marriage as the union of husband and wife,” he is definitively saying that public officials should be allowed to defy the ruling outright.

That, again, is a step Lincoln never took.

* George quotes Lincoln as saying, “the people to cease to be their own rulers, having effectively abandoned their government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.” Lincoln’s actual statement is this: “the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.” Again, a minor misquotation.

Shares