The twist in last night’s “Frontline”—a co-production, this week, with PBS and ProPublica—occurs about 32 minutes into the investigation. Up until then, “Terror In Little Saigon” is interesting but not exactly compelling; though the story of a string of unsolved murders in Vietnamese-American communities across the country is unsettling, the investigation has not yet made for really watchable television.

Then the investigator and narrator, A.C. Thompson, finds something in the immigration paperwork of a man he believes to be involved in the murders—the signature of Richard Armitage, former Deputy Secretary of State under President George W. Bush. And in that same paperwork, 30 years after this now-deceased man applied for U.S. citizenship—six blank pages, redacted because they are classified.

It’s the type of turn that, in a fictional story, would mark the sudden cascade into a chain of unstoppable events, as the heroes discover the true extent of their mission. In a work of journalism, though, it’s harder to get there. Thompson tries to find out whether the American government funded a small but violent group of Vietnamese anti-Communists—an organization called the Front, which had roots in Vietnam, Thailand, and all over America, and openly desired to restart the Vietnam War. But there’s almost nowhere to go; most of the Front’s ringleaders are dead, the relevant government agencies refuse to speak to him, and the other journalists that covered this story were the ones killed in the ‘70s. The documentary ends on the unsettling note that such a thing probably could have happened. Implied in the closing narration is that the story probably could be pushed further, but that is the end of this journalist’s time and resources.

“Terror In Little Saigon” could have been structured more strongly. It’s hard to find the urgency of solving the murders in Thompson’s narration or in the frequently subtitled interviews with Vietnamese-American community members. There is an art to making real life into compelling drama, and “Terror In Little Saigon” does not have the haunting intimacy of “My Brother’s Bomber,” also from “Frontline,” or the 12-hour rigor of Sarah Koenig’s “Serial,” or the funds and personal interest of Andrew Jarecki’s “The Jinx.” Even when the facts become shocking, the documentary suffers from a lack of urgency.

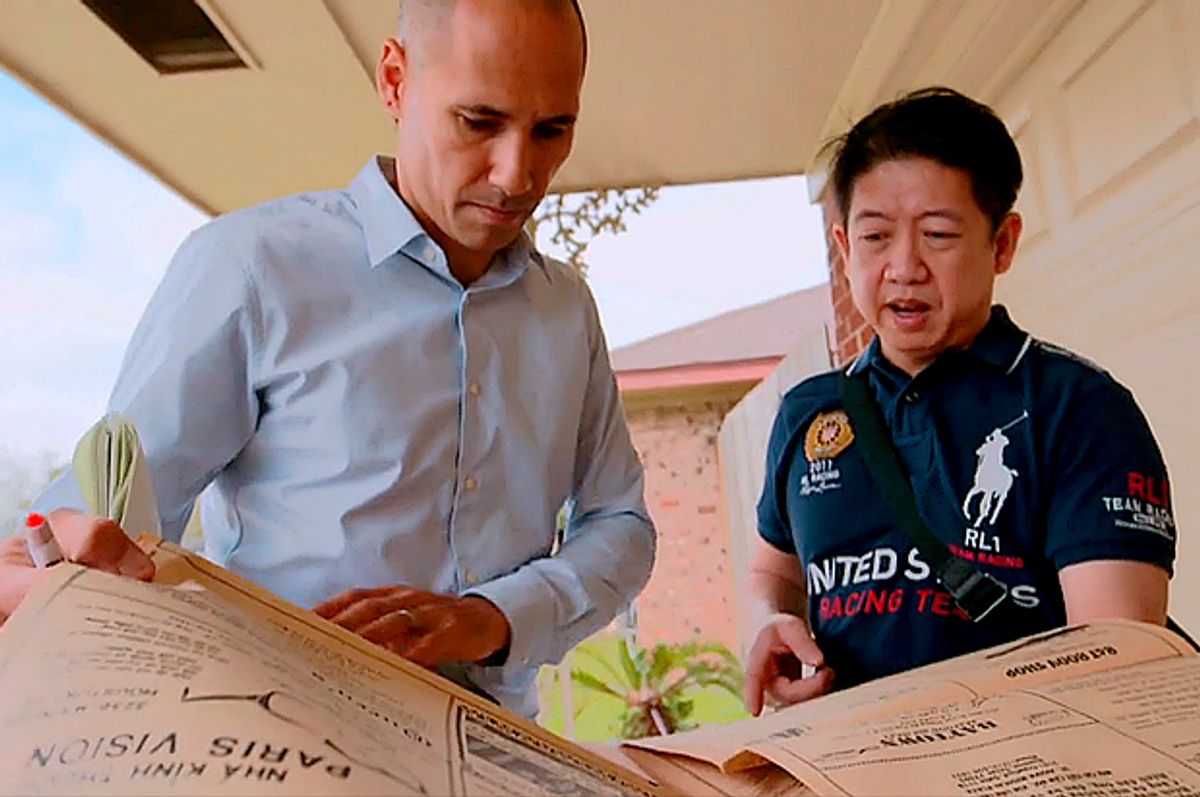

But what it does have is a story of embattled journalism. Thompson is brought into this story through the investigation of murdered journalist Nguyen Dam Phong in Houston, Texas—the type of crime that would typically horrify the public, but was overlooked and neglected at the time by the police and the media. He’s drawn into investigating other murdered journalists—most notably, one in San Francisco, that was similarly ignored by police. Then, after finding the Armitage connection, he travels to Thailand and Vietnam, looking for the Front’s training base. His search is largely fruitless; the interviewees he does secure there are even less cooperative than the ones in America.

And of course there is the story of ProPublica itself, a nonprofit organization that produces investigative journalism because there’s less and less of a market for it; and of “Frontline”’s home network PBS, whose funding is constantly undermined by the right—and whose entire content budget is less than the promotional budget for one big HBO series. “Terror In Little Saigon” runs out of time and money before it can get to the bottom of this story, and that feels just as hopelessly tragic as the murders themselves do.

At the very end of the documentary—as a way to put a button on what has been an unsatisfying voyage of unanswered questions—Thompson goes back to Houston to visit Phong’s two sons and apologizes to them, on behalf of the rest of the world, for not paying enough attention when these lives were lost. It’s almost this apology from journalism, to journalism, for not caring enough—a kind of misplaced sentiment of guilt. It’s a very small sentiment of sympathy, all things considered. The sons are moved to tears.

Shares