The GOP race remains a mess which the pundits can't even begin to get their arms around. They have their favorite narratives—the Bush campaign on life support, for one. But we can all remember how confused and mistaken the knowing responses to the first debate were, while the certainties after the second debate proved ill-founded Still, they seemed compelling in the moment: Donald Trump was the “low energy” one that time around, and Carly Fiorina was widely hailed as the winner (naturally, Donald Trump disagreed).

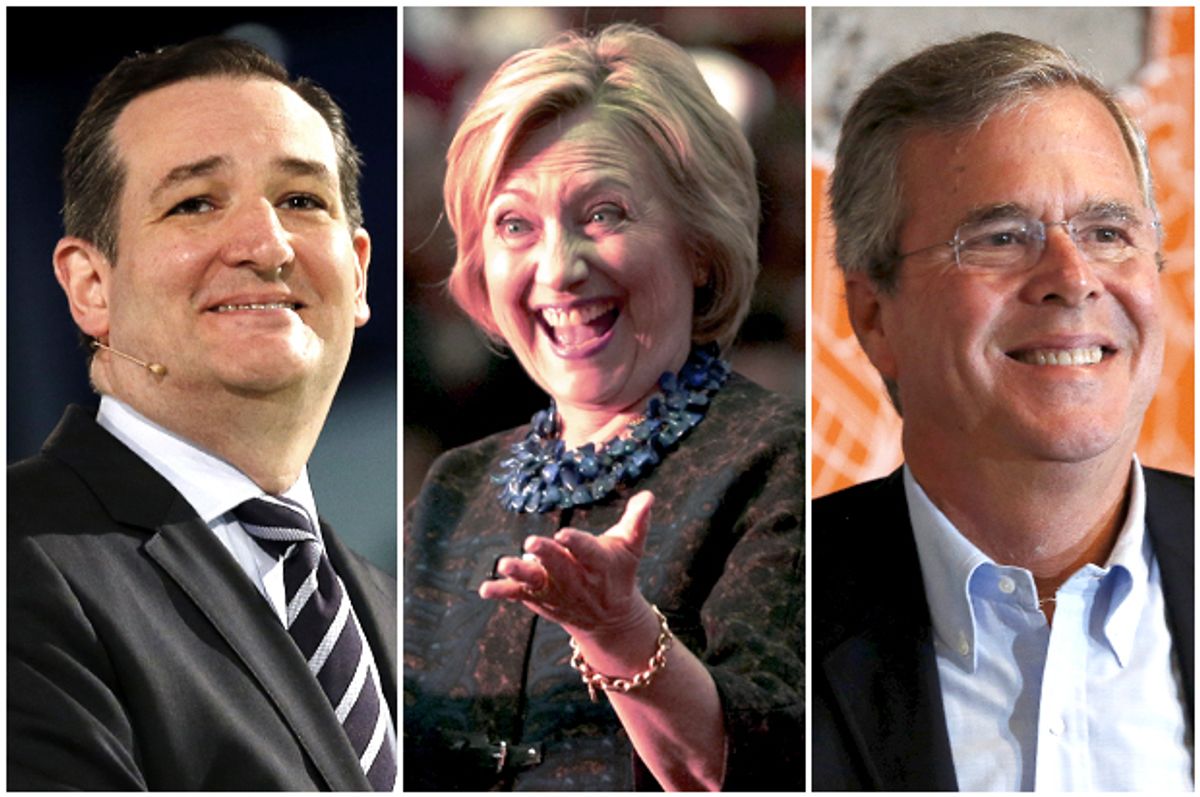

But as Digby had already detailed here, Fiorina was every bit as fast and loose with facts as Trump, as well as matching him in chutzpah. She was much more in line with what the establishment wants, however—all the appearance of outsiderness with absolutely none of the substance. With Hillary Clinton still the expected Democratic nominee, and its activist fraud wing going ballistic over Planned Parenthood at the time—to the point of threatening another government shutdown, the party desperately needed a way to counter Clinton's potential appeal as an historic feminist first, and Fiorina has always counted on this as her affirmative action route to the nomination. And so it was that a small, very brief Fiorina boomlet ensued.

But, of course, beyond her media persona, Fiorina's real world campaign was notoriously thin, with early reports of outsourcing as much as possible to India, as well as to her own super-PAC. In short, she faced the same question as Trump before her: could she transition from a media campaign to a real one? Did she even need to?

In short, even the obvious media narrative coming out of the second debate came with some gaping holes. Their chances doing better coming out of this debate are not as good as pundits like to think. So sure they can write more stories about the woes of Jeb Bush—but those woes have been going on for some time now. More stories about them are unlikely to bring new insight into Bush's campaign, much less anything else. So we'll probably get more baffled stories about Ben Carson, stories more baffled than the earlier ones about Trump. That'll help clear things up, right?

What's really lacking is an overview grasp of the race, which isn't surprising, given how things are falling apart. Ordinarily, elections are primarily determined by fundamentals (as seen in the “Bread and Peace” model of Douglas Hibbs), with campaigns—however brilliant or inept—influencing outcomes only on the margins. Primary elections are more determined by how dominant factions on each side define the issue landscape, while most candidates try to show how well they fit that landscape, with occasional outsiders, mavericks or innovators who do more or less to try to reshape the issue landscape to their advantage. Ordinarily this gives rise to political races that are relatively simple to understand. Issue landscapes are relatively stable and well-defined, and although there are surprises along the way, they take on familiar forms that commentators are well equipped to analyze and discuss.

Recently, however, the GOP's internal cohesion has been shattered, in part because of epic policy failures (9/11, the Iraq War, Katrina, the Great Recession) and in part because of structural changes empowering entities like super-PACs which diminish the relative power of cohesion-oriented party organizations. As a result, this cycle has seen unprecedented fragmentation, and a lack of issue landscape stability. In fact, the dominant candidate, Donald Trump (who still has a healthy polling average lead, despite Ben Carson's recent gains) doesn't define himself in terms of issues at all, but in terms of attitude. In retrospect, even his initial seeming fixation on immigration was as much about Trump's attitude—if not more—than it was about those who called “rapists” and “murderers.” And so it's difficult for observers to say what's likely to happen, because they're having a hard time understanding what's already happened so far. And the rise of Ben Carson is only making that worse, not better.

So here's a suggestion. Rather than trying to understand what's happening in terms of more candidate than you can throw a stick at, let's try thinking about groups of candidates, .who share enough in common that implicitly define a shared issue landscape, implying a shared set of assumptions—even if there's some inherent fuzziness in exactly what that landscape is.

For example, establishment pundits are limited in their understanding, because they're accustomed to think in terms of the establishment they're part of, and within that establishment, being a presidential contender means being an elected politician. That's a big part of what defines the issue landscape—as well as campaigning style. But in this election cycle, Trump was always only the loudest and most dominant of a group of three candidates who'd never held office before (although in Fiorina's, not for lack of trying). So there are two obvious choices: we can try to understand things in terms of the establishment candidates, or we can try to understand them in terms of the outsiders. Or we can try a bit of both—which is what I'd like to suggest.

Let's start by setting the outsiders aside for the moment—not because they're irrelevant, but because they've been so dominant it's been hard to see beyond them—and looking at the remaining group, those who the pundits are more accustomed to dealing with. Within this the outsiders removed, a Huffington Post customized polling average overview shows that Jeb Bush has held a lead almost continuously for most of the past year and a half, albeit not a very impressive one. Rubio has moved past him since late September, but he's slumping along with Bush the last few weeks, a pattern seen when Scott Walker (remember him?) eclipsed Bush from early April to late May. Recalling how many times Romney saw others surge into the lead ahead of him, one can't help realize that Bush doesn't look so bad comparatively, if only the race had remained limited to elected politicians—as it has for almost all of our history. Sure, his percentage of the total vote was always historically low, but that could be attributed to an unusually overcrowded race. So, take out the outsiders, and this race doesn't look very unusual at all.

Jeb's total support has been very low in absolute terms—not surprising given the overcrowded field—but it's shown the kind of long-term dominance which has, in the past, been a sure sign of a winning GOP primary campaign... eventually. Rubio's recent modest edge notwithstanding, this record, in combination with the way pundits think, and the world they expect to see, helps to explain why Bush has remained a significant figure, despite registering in single digits, on average.

This is the world that the pundit class knows and understands—to the extent that it understands anything. But they have a hard time grasping its limits—or what lies beyond. And that's been a source of constant consternation ever since Trump entered the race, if not before.

Fortunately, we can get a clear sense of just how limited that view is in this electoral cycle. To do so, we expand our view in one way, while contracting it in two others: We add outsider candidates who've never held office before, but only consider candidates currently polling over 2% (plus Scott Walker, for his past role in the race), and we only consider the race since April 1 of this year.

You can see the results here: the outsiders first Trump, then Carson) rise, while the insiders fall (note that Fiorina's rise and fall looks typical of insider). No news there, really. But just take another look at the first chart, and remember, if there were no candidates running who'd never held office before, that is how the race would look, instead of like this. What we're seeing here is not a tale of one or two candidates, although that's what it looks like What we're seeing is shift in perception of what it means to be an outsider.

So now let's shift our focus entirely toward the outsiders. But in order to understand their influence, let's let "outsider" have a looser meaning. We include those who've never held office, of course, but also those who looked like outsiders before this new crowd arrived: Ted Cruz, Rand Paul, Mike Huckabee and Rick Santorum. The last two are outsiders in the sense of being uncompromising religious right candidates, representing a constituency that's always disappointed in getting what it's been promised. Paul is a libertarian, which puts him at odds with the GOP establishment in several ways—from the war on drugs to war in general—while Cruz has been a bomb-thrower in Washington. If Trump and Carson weren't in the race, all four of these candidates would have a shot at defining what “outsider” meant for the GOP this cycle, and in turn, a shot at defining conservative identity as well. Limiting ourselves to candidates over 2% again, Santorum doesn't make the cut, you can see what the post-April race with the rest of the outsider field looks like here.

All the "outsider" office-holders and former office-holders have suffered since first Trump, and then Carson surged. Cruz has suffered the least (falling from 8.4 to 5.5%) by aligning himself vocally with Trump, and Rand Paul has suffered the most (falling from a high of 9/1% down to 2.%) by emphatically attacking Trump, while Huckabee splits the difference (falling from a high of 8.4 to 3.5%). This is a clear-cut statistical demonstration that (up to this point, at least) Donald Trump as someone who's never held office, has redefined what it means to be an outsider, redefining the term as a context that Cruz, Paul and Huckabee have no choice but to accept. It doesn't seem strange at all to argue that in doing so, Trump opened the door for Carson's more recent rise, following the first debate.

The door also opened for Fiorina as well, but she peaked very quickly, only reaching 7.7% in late September, less than half of Carson at the time, and it remains to be seen if she can bounce back—which, by the way, Trump has already done, another basic fact about the campaign shown on this chart that the media seems to have missed. It's strange to hear all the recent coverage about Carson taking the lead, when the polling average shows Trump still more than ten points ahead, and shows that his real problems showed up in September, most of which he spent in a slump, falling from 31.5% to 28%, and then recovering in October, up to 32.3% at the time of the debate. Carson's rise has been much more steady, with only a brief plateau from September 15 to 23. Aside from that, he's improved almost continuously since August 4 when he stood at 6.9%, just barely above the “outsider” electeds, up till the third debate, which found him averaging 21.7%.

Now let's expand the notion of "outsider" a bit more, to include candidates elected with Tea Party appeal and big donor funding, which is how the Tea Party came to be in the first place (the Kochs and big tobacco, after all, have been working on the Tea Party brand for years). This adds Scott Walker and Marco Rubio to the mix. The results can be seen here.

Until Trump began his accelerated rise, Walker and Rubio were leading this group, but both have fallen since. Walker, of course, has left the race, falling from 12.8% to 1.8% before departing, a drop of 86%, while Rubio—who regained a lot of ground in September, but inched down this past month—has fallen from 11.3 to 8.4%, a decline of only 26%—which makes him hot stuff in the eyes of the pundit class. The contradictory combination of big donor money and rabble-rousing little-guy rhetoric defined Tea Party "populism", but Trump has happily eaten it for lunch. There is no Ted Cruz strategy for softening the blow to be found here. Which is why the pundits are right for once—it actually does make sense to talk about Rubio as an establishment candidate. For all his years of flirting with various outsider poses, there's just not a lot of traction for him there.

What does all the above tell us about the race to come? Nothing specific. In fact, it strongly suggests that specifics will continue to change unexpectedly and unpredicatably. But in does suggest something in general, which may or may not shed some light on what may happen next. If we think of the race in terms of factions, not individual candidates, we have four contenders in the race: the “outsiders” (Trump, Carson, Fiorina), the “outsider electeds” (Cruz, Paul, Huckabee and Santorum), the “Koch/Tea Party” block (Walker and Rubio), and “establishment electeds” (everyone else).

As I read all of the above, this race has seen a dramatic crumbling of the establishment—so dramatic that it's taken down the old would-be outsiders every bit as much as it's taken down the establishment pillars. Rubio is the only one remaining in his category, which is really a source of strength, but 5-poll running totals for that block peaked at 31.4% in early May, and Rubio owned less than half of that: 15.2%. He'd drool over such numbers today—almost twice his 8.8% pre-debate 5-poll average—and the thought of getting Walker's voters then as well? It's hard to imagine, given how the outsider's support has grown, from 8.8% back then to 57% now, in the last pre-debate 5 poll average.

The outsider block has been over 50% [5 poll average] since September 2, and thanks mostly to Carson, it stayed above 50% even as Trump lost a bit of ground that month. With both candidates gaining ground in October, there now seems to be a real possibility they could break 60% at some point soon.

All the other groups are in a state of collapse. The “outsider electeds” 5 poll average peaked at 37.2% all the way back in March, 2014. They haven't been above 20% since July, and now stand at 12.8%. We've already seen how the “Tea Party/Koch” block has fallen. The “establishment electeds” peaked at 33% [5 poll average again], and stand at 16.2% today—less than 1/6 of the total voters. Even they haven't been above 20% since late August. Remember when summer was supposed to be the “silly season,” and now was when things were supposed to get real, with the “grown-ups” back in charge? Things are so bad for the establishment that even if Bush had totally dominated, driven every single other establishment candidate from the field, and captured all of their voters, that would only give him 16.2%--barely more than half of Trump's total, and 4 points behind Carson.

These trends don't mean the establishment is done for. It very well could be. Or it could be up for grabs. Remember what I said about outsiders and mavericks who “try to reshape the issue landscape to their advantage”? That's what I think is happening now. The candidate most likely to surge next is the one who can do the best job, not of adapting to the political world around them, but of reshaping that world to their advantage. If they can bring enough of the establishment along, they will define the new establishment.

That's precisely what Carly Fiorina tried to do after the first debate. She used the GOP's own profound anti-female ethos against it, taking full advantage of the very sort of affirmative action which she joins the rest of the party in ritually denouncing. She is (as noted) just as dishonest and duplicitous as Donald Trump, but she's come of age in a different time, and that gave her an edge that the rest of her clumsy male cohort seemed to lack—for a time.

This is probably the best lens to view Ben Carson with—and anyone else who actually does manage to gain some momentum. Facts will not be an issue during the GOP primary, only the crafting of appealing fantasies will matter, and anyone who is capable at that, a la Donald Trump, has a shot at going all the way. But winning the nomination will not be the ultimate prize this cycle. Reshaping the issue landscape will be. Given how grotesque it already is, I shudder to think what that will look like in the end.

Shares