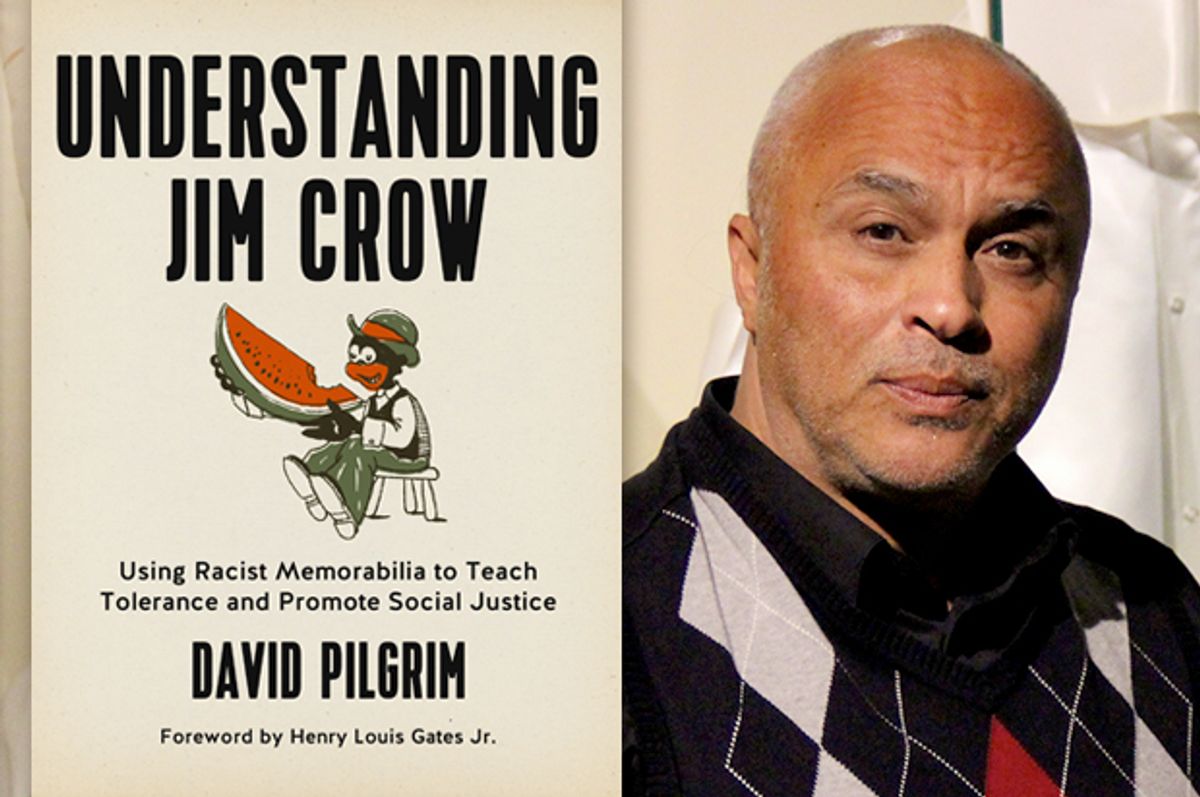

The language and images are hard to take – a black man with enormous lips eating a watermelon. Black women in exaggerated sexual poses. Broken English and racial slurs. They’re all important parts of "Understanding Jim Crow," a new book subtitled “Using Racist Memorabilia to Teach Tolerance and Promote Social Justice.” Whether the book inspires tolerance or social justice, it certainly makes the existence of virulent racism hard to deny.

The book’s author, professor and activist David Pilgrim, began collecting racist items as a child, and now presents them at the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University in Michigan.

“There was nothing understated about Jim Crow during that long, blistering century between the end of Reconstruction and the seminal legal victories of the American civil rights movement,” Henry Louis Gates Jr. writes in the book’s foreword. “Racist imagery essentializing blacks as inferior beings was as exaggerated as it was ubiquitous. The onslaught was constant.”

We spoke to Pilgrim from his university office; the interview has been slightly edited for clarity.

I probably don’t have to tell you that these images are pretty disturbing. Why is it important that people see them?

I don’t remember who it was that said an image is worth 1,000 words. But what we’ve discovered is that when people come to our facility, and are confronted with the visual evidence of Jim Crow, it changes the discussion.

I can try to use my words to paint pictures… But when they come to the museum, they’re looking not just at two-dimensional images but sometimes three-dimensional objects. So they’re really confronted with evidence of the racial hierarchy.

When did you start collecting these images? What drew you to them?

I wish I had a better story. I wish I could tell you that when I was 13 years old I had a premonition that I’d be a great human rights activist. The reality is when I was 12 or 13 or 11 I happened upon a Mammy figure on someone’s table – a dealer. In those days down South, you’d have a carnival and someone selling used objects, just a hodgepodge. I bought a piece, I destroyed it. I don’t think there was anything particularly deep going on in my head except that I didn’t like it.

I don’t remember the second or the third or the fourth – but I was always collecting. Keep in mind, in those days, this stuff was everywhere. So the ideas that eventually led to this becoming a museum were spread over four decades or more.

For people who’ve not seen the book or the museum, give us a sense of some of the images we’re talking about here.

The museum focuses on everyday objects. We thought it was important to recognize that… the average American had in their homes postcards and games and toys and sheet music and ash trays… If you can think of an everyday, common object, there was a racist version of it. They both shaped and reflected attitudes about African-Americans. You would have images that reduced them to one-dimensional caricatures like the tom, the coon, the sambo, the mammy. All minority groups have had that happen, but not as often and in as many ways as African-Americans.

When you lead tours of the museum, are there people who are shocked, who tell you that these images shouldn’t be made public because they’re too distasteful?

I used to hear it more – and I only really hear it these days from people who haven’t been in the facility. I don’t mean to be immodest, but just think the museum is set up in such a professional way. I think even though it’s horrible and ugly, it’s placed in a context… One of my goals was to re-create the experience so you feel like you’re standing in a history book.

So I think people get it. That doesn’t mean they’re not shaken when they come. I think the most common response is a kind of reflective sadness. I think it would be a failure on our part if that’s how they left. The purpose of the museum is not to create feelings of sadness, but to be useful as a tool for having meaningful dialogue. We’re not a shrine to racism, and we’re not a house of horrors: What we are is more of a classroom.

Nonetheless, there are emotional pieces there, and over the years I’ve had two or three times where I lost my balance.

The cover of the book has a picture of a black guy eating a watermelon – a classic racist image. I guess the implication of that is that black people are simple country bumpkins…

That was a game card… So a lot of people, white people, who in the safety of their home, they live out what they think it means to be black… It’s like blackface in the 1800s, or pimp-and-whore parties today. In other words, it’s not just an image, but an image that was functional.

An image like that says that black people are simple and non-threatening. What are some of the other stereotypes the Jim Crow era traded in, that we see in your book?

Images emerged after Reconstruction of a more threatening black person… Whereas, 15 years after the Civil War ended, you had the “silly coon” on minstrel stages; by the 20th century, that silly coon had become a razor-toter who used his razor against whites… So the fear was that this brute would hurt white people. A lot of black people were brutally killed and rationalization is that they were threats to the larger white society. Some of the most horrific lynchings occurred because a black person had been accused of doing something to a white person, often falsely accused… And that hasn’t died out yet.

Many of the images in your book are a century or more old. Have we seen a rebirth of this sort of thing, perhaps since Obama’s election, online or elsewhere?

Certainly President Obama has been a cottage industry for racist imagery and racist memorabilia. There was a time in my collecting career, two or three decades ago, when there was a definite dip, in the production, sale and purchase of these really harsh, nasty images. But that has returned. In the museum we have a section of new objects; some of them are made to look old.

I do believe that America is more democratic and egalitarian than it has been for most of its history. But race still matters in the U.S., and negative racial imagery is one way you can see that it matters. You cannot have a race-based incident in the U.S. and not within one week have material objects in the market being sold reflecting the incident.

Shares