Thanks primarily to Donald Trump, the 2016 presidential campaign has already upended most observers' expectations, as well as their previous estimation of just how insane the national politics of the world's leading superpower can really be.

However, one of the lesser-noticed ways in which this campaign hasn't gone according to script has nothing to do with "the Donald." Rather, it has to do with women's economic power and reproductive health. Despite the 2016 campaign's taking place in the post-"Lean In" era, despite a woman being the odds-on favorite, and despite the increasing prominence of "women's issues" like paid family leave and abortion rights, the campaign has been overwhelmingly about ... other things.

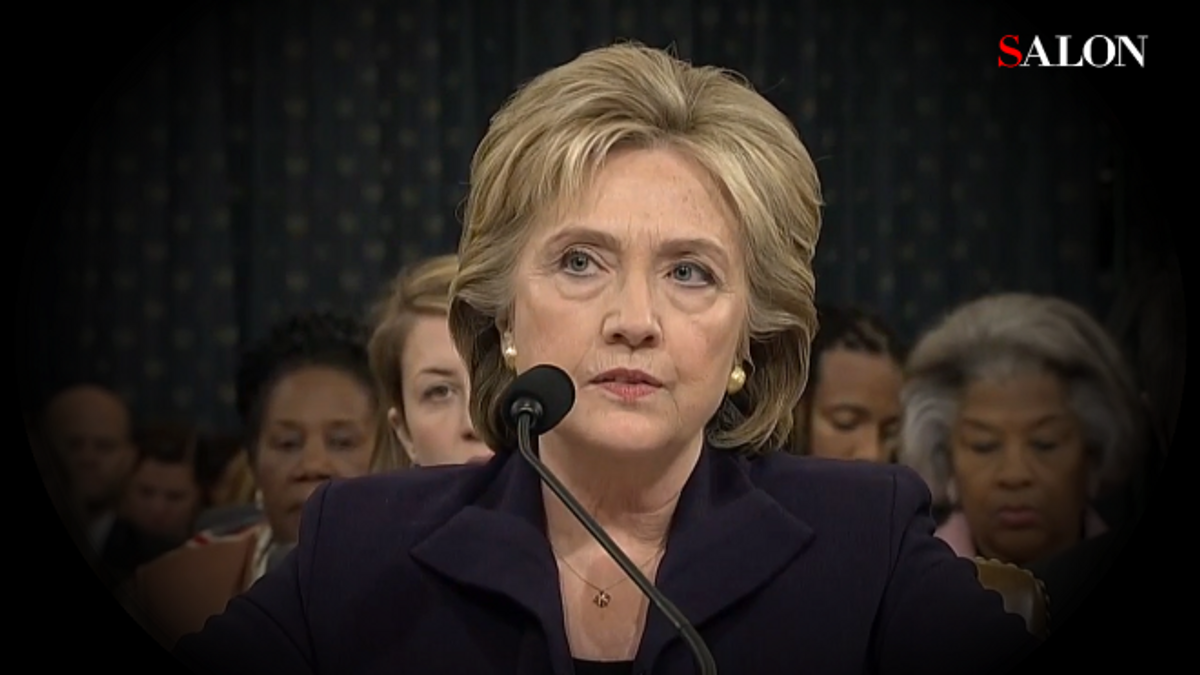

Because we were interested in bucking that general trend, Salon spoke over the phone recently with Andrea Flynn, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute who focuses on those public policy issues that especially matter to women and to families. Alongside a discussion of one of the leading Republican candidates' paid family leave proposal, we also touched on the ongoing war against reproductive rights, and what Hillary Clinton can do to make the link between women's health and women's economic standing more explicit.

Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

Let’s start with Sen. Rubio’s paid-leave proposal, which you wrote about for the Atlantic. Rubio’s tried to present himself as a more forward-looking Republican, and he’s cited this policy as a chief example. How does it hold up when given a close look?

He has come out with this “pro-family” message, and has at least acknowledged the challenges working families are facing. He is, to my knowledge, the only Republican who has put forward a paid family leave solution. His plan is very different from what the Democrats are proposing so far.

What’s one way in which that’s true?

His plan would [affect] companies that are already inclined to discuss [paid leave] and to do the right thing. It would not extend the benefit to middle- and low-income workers, who really need the benefit and don’t have access to it. So, my fear is that Rubio’s plan is “good,” because it addresses the issue that lack of paid leave is very problematic for families, but it doesn’t actually guarantee that families are going to have access to that benefit.

And when it comes to women’s reproductive health, Rubio’s pretty extreme. He’s against abortion even in cases of rape and incest, for example. In this sense, he benefits from the figurative wall we tend to maintain between “social” and “economic” issues.

That’s not just a phenomenon on the Republican side; Democrats also do it. There are really a number of progressives right now who have made a strategic decision to leave out reproductive healthcare while pushing for movement on the economic issues. So there are two different things happening.

On the Republican side, there is such a heightened vitriol over reproductive healthcare — in a way that we haven’t seen before. The right used to be focused on challenging abortion access, but it has now extended the attacks to include more [aspects of] reproductive healthcare and family planning. They are not interested in talking about reproductive healthcare in an economic context. They’re more focused on fetal rights (to the exclusion of what women and families experience when they cannot access healthcare).

And what about among Democrats?

On the Democrats’ side, some would view it as politically risky to include reproductive health in a progressive, economic agenda. But what I don’t understand is how we expect women and their families to make the best of all these other economic benefits and programs when they don’t have access to basic care.

Well, Secretary Clinton’s campaign has tried to portray her as a fighter for working families and, in general, depict her in a kind of matriarchal, “pro-family” light. How are her policies in that regard matching up with her rhetoric?

I think given what we are seeing at the state and national level, it is really surprising and unfortunate that she and other candidates have not put this issue [front and center] on the national stage. I think that her policies are in the right place; but she should be talking about them more loudly, and telling the American people that she understands the reproductive health crisis, and what that means for women and their families.

I want to return to the idea of there being an ongoing “crisis” when it comes to reproductive rights and access to reproductive healthcare. But before we go in that direction, are there any pro-women economic policies that you feel are on the precipice of the mainstream? For example, the $15 minimum wage went from being on the fringes a few years ago to being on the left-most edge of the mainstream today. Are there any policies you think could make a similar jump through the 2016 campaign?

The first is on the paid family leave front. I am a mother myself; I am very excited with the momentum on paid family leave. But I hope that in the coming years we start talking about 12 weeks as the floor for what is expected. Countries all over the world have policies that give both men and women between six months to a year to 18 months. A guaranteed 12-week paid leave would be an enormous improvement from where we are right now. But we should also be thinking of 12 weeks as the bare minimum that families need to take care of themselves and their children.

On the health front, there has been increasing momentum around repealing the Hyde Amendment, which is the law that prevents women who have Medicaid coverage from using that coverage for abortion services. And there is an increasing amount of energy around this bill called the EACH Woman Act, which has gotten a significant amount of support.

To return to the point about there being a growing “crisis” with regard to women’s reproductive health, I’m sure you’ve seen the recent study indicating that tens of thousands of women in Texas have been forced to induce their own abortions because they can no longer reach a clinic. Should we be surprised by these numbers?

This is not surprising. The experts predicted that this is exactly what would happen. Texas has got a lot of attention over a bill that is responsible for closing more than half of the state’s clinics. But, even before that, starting in 2011, state lawmakers slashed the family planning budget and closed family clinic services. This is all happening even before HB 2 is put in place.

Lawmakers have made it exponentially more difficult for women to practice family planning; and then they have passed a law making it exponentially more difficult for them to access abortion services. I’m not really sure what lawmakers thought would happen, but experts predicted that [self-induced abortions] would happen. More women would experience unplanned pregnancies, the need for abortion services would increase, and women who needed abortions were going to find ways to get them — even if they are self-inducing. This recent research shows that that is exactly what is happening.

What should the policy implications for the future be, given Texas’ experience?

You would hope that this data would conjure a reversal of the current policies. Unfortunately, lawmakers have ignored the data when it comes to reproductive health. They’ve made up their own rules and own justifications for why they are passing these laws. They say they are passing them to protect women’s health; but as we’ve seen in Texas, the exact opposite is happening.

Arguments about equality and empathy don’t carry much water with these folks, obviously. (At least not on this issue.) But what about an economic case? What’re the economic consequences of these policies?

There are a few different ways to think about it. One is to think about what is the financial cost of having a child. What is the cost of now having to access care that is hundreds of miles away? You have to access it over a few days, and that’s a great cost. There is a good study that shows the economic costs for women who tried to access abortion and couldn’t. It showed that women who were denied abortion had three times greater odds of landing in poverty. So there are extreme economic consequences for women who cannot access the healthcare that they need and want.

What about on the macro level?

I imagine we are going to see more health costs for the state. When lawmakers in Texas initially passed both the restrictions on family planning and the antiabortion bill, they were warned that they would be bearing the costs of unplanned pregnancies, many of which will result in children who need to be supported by the state. If the women's health predictions weren’t dire enough, the economic predictions — which at one point had conservatives supporting family planning — did not really make a dent. At this point, the economic argument is not even moving them.

Right. And given that context, I must say, I’ve wondered if the talking point about how far women in Texas now have to drive to get an abortion is misguided. It’s powerful to those who already believe in reproductive rights, I’d bet. But I doubt people who are on the fence are quite so sympathetic.

When we think about what has happened in Texas, and what is also happening in other states, I think it is important to [recognize] that conservatives want to suggest that these policies are only impacting abortion access. But they aren’t; these policies are impacting access to basic care. What is happening here is that this attack on abortion access has spilled over. It’s now restricting access to all kinds of care.

The question we need to be asking is, are we really OK telling women that they can’t even be provided healthcare of their own choosing, that they have to travel to get [care]? When these clinics close, women can’t just go to the other healthcare provider down the street. That’s simply not the case. It is not as if there are a bunch of providers who are standing there and waiting for patients when these reproductive health clinics close.

And the other thing I would say about that is that when we talk about women having to travel to get healthcare, there are real economic implications.

How so?

Basically, what we’re saying is, if you have the ability to access care near you, you can do so. But if you are poor, low-income or [an] immigrant, you’re going to have to travel.

You might not be able to for a variety of reasons — your job does not give you time off, you don’t have paid family leave, you don’t have a baby sitter for your kids, your kids are in preschool, you don’t have transportation, etc. — but you enter this intersection of structural barriers that makes it very difficult. So when we implement policies that tear away at the reproductive health infrastructure in this country, what we are basically doing is increasing barriers that make it much harder for people who are already marginalized to get the care that they need.

Shares