Early this semester, one of my young Black male students shared with our class that each time he hears the story of an unarmed Black teenager being killed by police, he believes he won’t live to see 21. This week, after I shared with students the story of the police execution of 17 year-old Chicago youth Laquan McDonald, my heart dropped as I looked at his face.

As more details emerge about the massive local cover-up of officer Jason Van Dyke’s killing of McDonald, it becomes clearer that too many police departments around the country lack integrity when it comes to policing and being accountable to communities of color. This week’s news that Mayor Rahm Emanuel has fired the police superintendent Garry McCarthy will do little to restore Black faith in the system, particularly since Jason Van Dyke’s colleagues raised the $150,000 dollars necessary for him to be released on bail. Killer cops and the system that enables them do not only rob of us a belief in the trustworthiness of the system; they also steal something more fundamental from Black youth – a feeling of safety and a sense of personal wellbeing.

A recent study out from the American Sociological Association suggests that only about half of all Black youth ages 12-25 think they will live past the age of 35. Among Mexican-American youth, the number is even lower at 46 percent. Meanwhile two-thirds of white youth in this age range believe they will live past the age of 35. The study attributes perception of lower life expectancy to the disproportionate ill-effects of poverty that people of color experience, including lower over all life expectancies, severe health challenges coupled with limited healthcare access, and increased exposure to violence. My student helped me to understand that for Black youth, their feelings of hopelessness are also connected to their experience of a justice system that is adversarial to Black life and well-being.

This week, I will turn 35 years old. I have shared my own story about believing that I would never make it to my mid-30s. Like many of the young people chronicled in this study, I was exposed to extreme levels of violence in early childhood. I witnessed both my parents become victims, even losing my father to gun violence at age 9. He had been a victim of gun violence at least three other separate times in his life before succumbing at age 33.

That kind of exposure often communicates to Black children how precarious Black life is, but not necessarily how precious that life is also. But what this study also indicates is that most children and youth of color in the U.S., including Black, Latino and Asian youth, all of whom the study includes, feel profoundly unsafe. These children experience the acute stress of racialized poverty and of racism, regardless of class access. Exposure to violence at home, and in one’s neighborhood, coupled with exposure to violent policing, increases levels of stress that affect the health outlook for Black children and youth for the rest of their lives.

Safety is at the core of all these concerns. There are heightened conversations about safety in our public discourse at the moment. The attempt of students at the University of Missouri to create zones “safe” from media intrusion sparked a heated national discussion about the ways that the demand for Black student safety impedes the fundamental constitutional rights of all other Americans. In many college classrooms, students are increasingly demanding that professors make liberal use of trigger warnings in a bid to make the classroom a safe space, particularly around matters of sexual and gender identity. That discussions of racism may be difficult for students of color frequently escapes notice in many of these conversations.

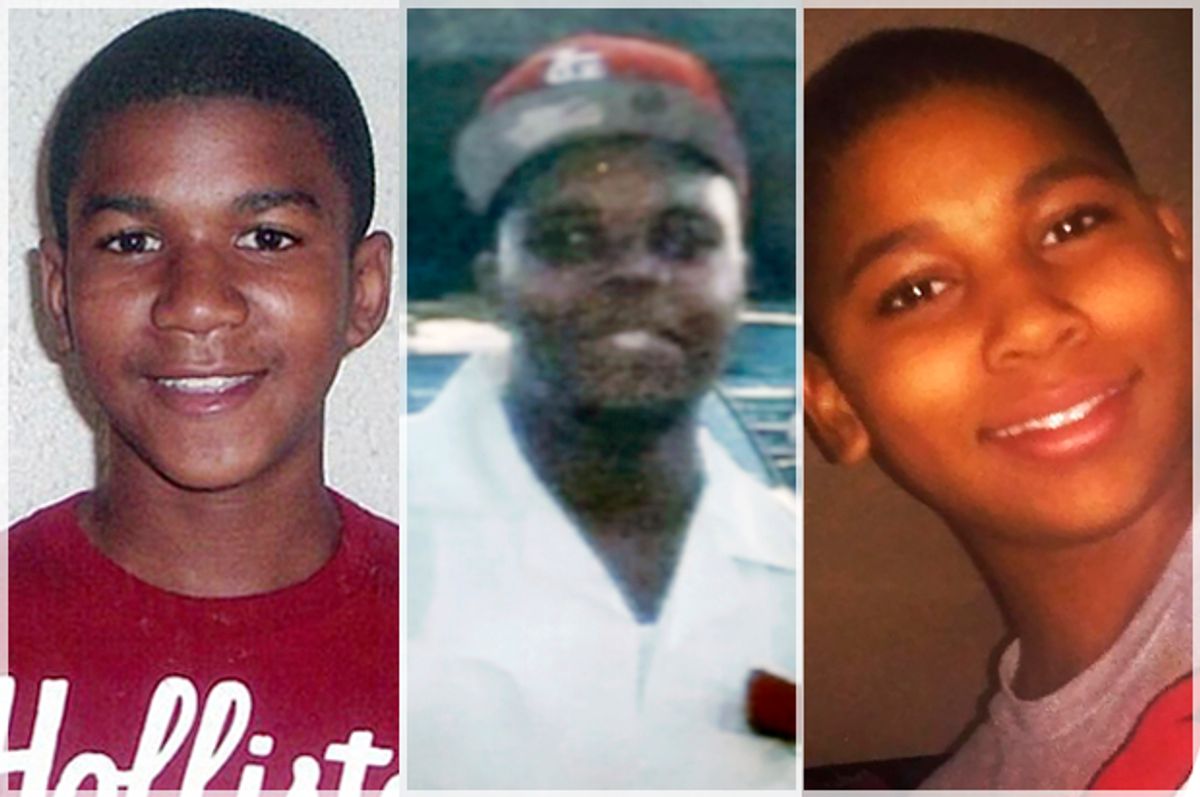

However, folks on the right parody these discussions of safety as mere liberal frivolity and descent into political correctness. Less attention is paid to the manner in which the right wing deploys notions of safety and threat in ways that do incessant harm to people of color. Most social policy on the right, whether we are speaking of tough-on-crime policy or anti-immigration legislation, is offered to us as a way to “protect” the American way of life. White safety from people of color, whether Black people integrating white neighborhoods or Syrian refugees trying to gain entrance to Indiana, iw what drives right wing social policy. Remember that George Zimmerman killed Trayvon Martin in the name of protecting other white families who lived in the neighborhood. A cop in Charlotte, NC, killed Jonathan Ferrell, because he thought that the young man, who had just had a bad auto accident, was trying to rob a white family, when he knocked on the door asking for help. Neither of these men were found guilty of their crimes at trial.

Rather than thinking about the variety of messages that all youth of color receive about how low a social priority their safety is, it will be easier for many to conclude that Black and Latino communities are more prone to violence because they place a low value on their lives. But this is why the proclamation that Black lives matter is so fiercely urgent. Latino lives matter, too. So do Asian lives. In a pro-white system, the basic nature of such truths seems to fade to the background. In this kind of system, the fact that prosecutors and police conspired to cover up the murder of a Black child becomes simply par for the course.

White safety is consistently offered as a blank check to justify our most horrid atrocities. Jason Van Dyke claimed that he feared for his life when he lied about Laquan McDonald approaching him and other officers and waving a knife. Recent antagonism to Syrian refugees also traffics in this disingenuous narrative of white safety. Youth of color are frequently cast as a threat to white safety and “national security,” while the murderous and violent racial antagonism of people like Dylann Roof, Robert Lewis, the Planned Parenthood shooter, and those who have posted recent threats to Black students on college campuses are framed as the misguided acts of singular individuals rather than as systemic threats to our way of life. But as Black Lives Matter protestors would say, “The whole damn system is guilty as hell!”

We should be concerned as a nation when the vast majority of youth of color born in the last 25 years in this country don’t believe they will be alive in the next 10 to 20 years. That kind of systemic hopelessness will cost us as a country, because young people of color do not see this place that we all inhabit as one where they can live and thrive. They see it as a place that will facilitate for them premature death, often at the hands of the state. If ever the powers that be become courageous enough to address racism and rampant inequality, America might have a fighting chance of being a nation fit to meet 21st century challenges. Otherwise, we will be a nation inhabited by youth whose lives have been marked for death.

Shares