On April 8, 1994 an electrician named Gary Smith, dispatched to install a security system at a four-bedroom, five-bathroom turn-of-the-century mansion in Seattle, found no one home. Peering through a window, he thought he saw a fallen mannequin. Once he realized it was the corpse of Kurt Cobain, the twenty-seven-year-old lead singer of the grunge band Nirvana, Smith called a local Seattle radio station before calling the police.

Three days earlier, Cobain, fleeing drug treatment, binging on heroin and valium, had shot himself in the head. The troubadour of trauma for the twentysomethings’ recently christened “Generation X,” Cobain felt crushed between the edginess of his art and the machinery marketing his music. Modern popular culture now specialized in domesticating musical outlaws so they could afford luxuries like the $1.5 million home Cobain and his wife, Courtney Love, had purchased that January. “The worst crime I can think of would be to rip people off by faking it and pretending as if I’m having 100% fun,” Cobain wrote in his suicide note.

While suicide rates had steadily averaged thirty thousand annually since the 1950s, teen suicide had tripled and suicide awareness had surged. Discussing once-taboo topics like this one fed demands to legalize assisted suicide for the elderly and the infirm. In 1990, Dr. Jack Kevorkian aided in his first public assisted suicide. He was arrested but acquitted. The practice had not yet been outlawed. In 1991, Kevorkian lost his medical license but continued crusading for this right, as a journalist, Derek Humphry, wrote "Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying." This how-to guide eventually sold more than 1 million copies.

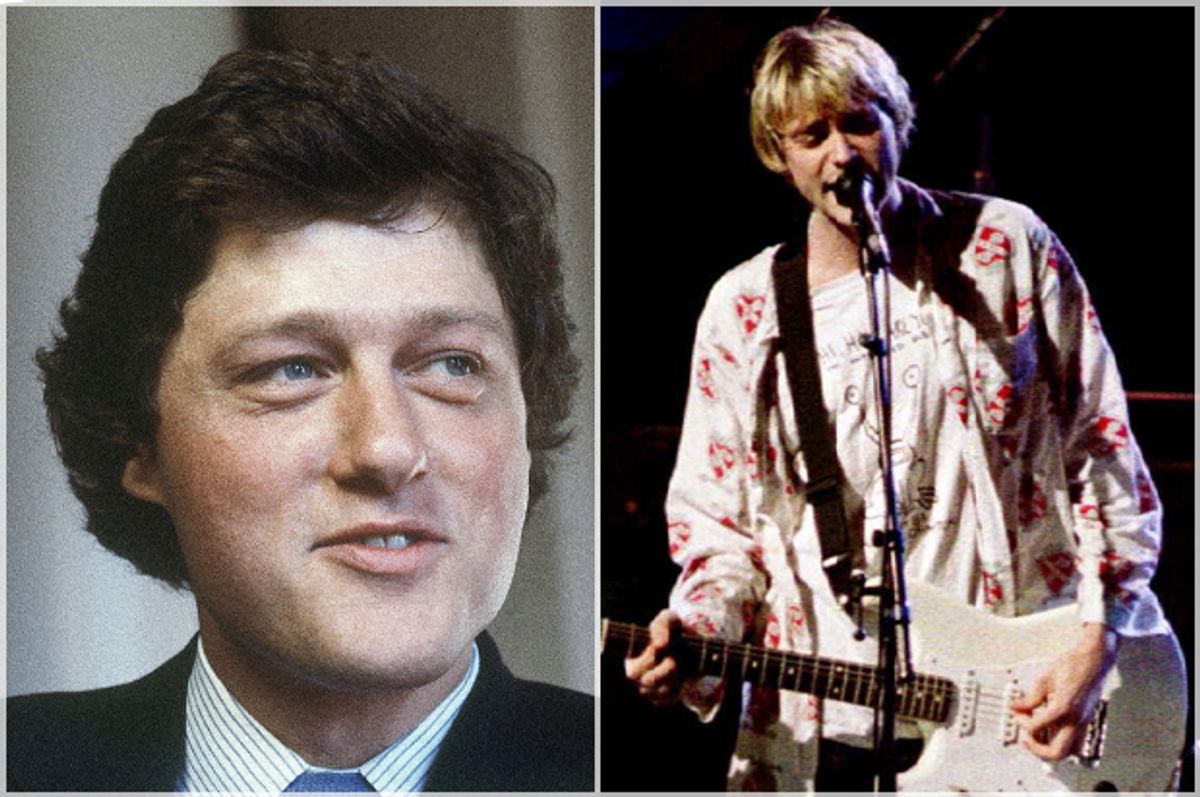

Kurt Loder, the MTV news anchor better suited to reporting on bands premiering than young legends buried, broke into regular programming to announce Cobain’s death. MTV’s producers pompously compared the following days of round-the-clock coverage to covering John Kennedy’s assassination. As millions watched MTV all night, burned Cobain’s signature flannel shirts in the park near Seattle’s iconic Space Needle, lit candles in memory of their tortured hero, many feared that the voice of the next generation had been stilled. “He was a geek and a god,” one fan told USA Today. “I really dug him.” Bill Clinton asked Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam whether to address the nation about Cobain’s death; Vedder said no, he feared encouraging copycats.

It was not just that Cobain’s was another musical Cinderella story, a child of divorce who was bullied in school, recorded his first album for $606.17, and saw his band’s second album, "Nevermind," sell 10 million copies. It was not just that “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and other Nirvana hits mixing depressing lyrics with sometimes surprisingly catchy tunes became anthems of angst for the surprisingly troubled masses. Cobain and his grunge group Nirvana helped make Seattle “the New Liverpool,” according to Rolling Stone. With equally gloomy bands like Pearl Jam, Mudhoney, and Soundgarden, Nirvana mixed hard rock, punk, and metal to create the “Seattle Sound,” expressing this New Nihilism. “I know there was nothing healthy about singing ‘Rape Me,’” one Nirvana fan wrote. “Kurt didn’t offer any solutions, he just railed against the ugliness and made it his home.”

Grunge—a label of disputed origins and elastic meaning—quickly metamorphosed from a musical style originating with young, edgy Seattle-based bands to a lifestyle appealing to America’s army of alienated and apathetic Peter Pans. The flannel shirts and leather jackets, ratty sweaters and torn jeans, long hair and layers of clothing, were purposely unglitzy, defiantly un-Eighties. Even the drug of choice switched from upscale cocaine to blue-collar marijuana. The grunge look professed to be carefree, despite its uniformity. It purported to be casual, despite how hard people cultivated it, especially after the budding designer Marc Jacobs’s spring/summer 1993 grunge collection. Most practically, it protected against Seattle’s cold weather.

Grunge, along with gangsta rap’s prison chic, punk’s masochism, and heavy metal’s exhibitionism, helped mainstream the use of tattoos, body piercing, and even some limited body cutting, as vehicles for self-expression and individuation. Kurt Cobain’s left forearm sported the brand of the small independent record label K, “to try and remind me to stay a child,” he said. The range of rockers’ tattoos, expressing friendship, longing, sentiments, politics, and sheer delight in oneself, illustrated the range of emotions that had as many as 20 million Americans tattooed by 1995. One hip San Franciscan told Newsweek these “identity bracelets” kept young people feeling bohemian, even when they sold out. New Agers sold tattoos to “bridge between the physical and the spiritual.” “I’m adorning my temple . . . ,” said one regular, who added more tattoos week by week, explaining: “It’s the only thing you have that can’t be taken away from you.” A Sunset Strip biker tattooist scoffed: “We’re not into that cosmic stuff.”

Freethinking child psychiatrists preached tolerance, defining these acts as the Nineties’ version of the World War II graffitist’s “Kilroy Was Here,” affirming the autonomous self in a volatile age. As America individuated, Dr. Andres Martin of Yale suggested, marking the body asserted power and established permanence. To cultural conservatives like John Leo of U.S. News & World Report, these “modern primitives” were repositioning “the sadomasochistic instinct . . . to look spiritually high-toned.” In the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville considered American individualism surprisingly uniform and conformist. In post-1960s’ consumerist America, the grunge rebellion, like most others, had been commodified, mass-produced, ritualized, and thus sanitized.

This commercialized, neutralized rebellion celebrating America the contingent, the evanescent, the depressing, imperiled Bill Clinton’s sweeping ambitions. This New Nihilism countered Clintonian bonding agents like responsibility and community. This nihilism was kinder, gentler, more indulgent, less harsh, less soulless than the original European version. Nevertheless, there still would be a certain lack of faith in the future, in community, in ideals and big ideas. As individualism and libertinism often made family ties disposable, as big ideas seemed less important with the era of big government ending, Americans— along with many Westerners—seemed to be rejecting many of the basic social and ideological givens that had structured society for so long—and that all humans need. Clinton wanted young activists, not young defeatists. In 1994, the Seattle-style apathy of the young who allied with Clinton culturally combined with the Washington-based antipathy of those who abhorred Clinton culturally and politically to imperil his presidency.

Seattle: A Capital of Horizontal America

America’s twenty-first largest city, inhabited by 516,259 in 1990, Seattle could lay claim to being the capital—or in Seattle’s true progressive spirit—a capital of the new horizontal America emerging. Seattle would be hailed as America’s grunge capital, America’s coffee capital, the headquarters of Gen X, the new hometown of one of America’s most popular sitcoms, "Frasier," and, perhaps, America’s funkiest city. Such defining firms as Microsoft, Starbucks, and Amazon would be headquartered in this, America’s leading “latte town,” or its suburbs.

Cities have their moments. Seattle’s combination of intensity, intimacy, angst, and ennui, worked particularly well in the 1990s. The Seattle Sound reflected the city’s gritty but wholesome, alienated yet oddly engaged, dynamic. If the World War II veterans were quintessentially Midwestern, wherever they lived, and Baby Boomers fused the Northeast with Southern California, alienated Gen Xers reflected a Northwestern vibe, as loose bolts from around America collected in that corner of the country. In 1993’s three-hankie, Oscar-nominated feel-good movie, Tom Hanks plays a widower who moves to the Northwest from Chicago. Before he finds love with the perky Meg Ryan, thanks to his flamboyantly cute if meddlesome son who turns to a talk radio therapist for advice, Hanks, in mourning, is "Sleepless in Seattle."

Douglas Coupland captured this Seattle Sensibility in his epoch-defining 1991 novel "Generation X." Coupland lived in Vancouver most of his life, which was like Seattle but with national health care and a tendency to end declarative sentences with “ay” and a question mark. In an increasingly national and homogenized America, popular culture was less about place and more about the collective experiences in the space the mass media shaped. Oozing what he called “Boomer Envy,” Coupland described young shiftless people with “McJobs”— enduring “Low pay, low prestige, low benefits, low future”—experiencing “Mid-Twenties’ Breakdown,” resenting that “Our Parents Had More,” as America underwent “Brazilification,” with the gap growing between rich and poor. The “Lessness” was economic and cultural. These socially, emotionally, and culturally deprived young people fought consumerism by insisting “I am not a Target Market” while succumbing to it, seeking deeper connections even as their “Divorce Assumption” and their “cult of aloneness” viewed all relationships as disposable, a logical conclusion with half of all marriages dissolving. They were overwhelmed by too much technology (i.e., “cryptotechnophobia”), too much choice (i.e., “option paralysis”), and too much freedom (i.e., “terminal wanderlust”).

The Bored and the Shiftless, in Movies and on TV

By 1994, many critics tired of Coupland’s kvetching. His third book "Life After God," a short story collection, evoked contempt from one reviewer for rehashing the same “self-pitying, small-scale ennui of Generation X.” Still, while Coupland showed that Generation X could be an entertaining and lucrative literary subject, the inevitable generational movies mostly failed commercially. "Slacker" (1991), "Singles" (1992), "Reality Bites" (1994), and "Clerks" (1994) were clever, ironic, evocative. In "Reality Bites," a young Ethan Hawke plays Troy Dyer, a coffeehouse guitarist struggling between subversive idealism and nihilistic cynicism. When a friend wonders “why things just can’t go back to normal at the end of the half hour like on "The Brady Bunch" or something,” Troy replies: “Well, ’cause Mr. Brady died of AIDS.” Robert Reed, who played the all-American 1970s father, died as a closeted gay man with HIV.

Unfortunately, movies about bored, shiftless drifters left viewers bored and restless. Ben Stiller, the twenty-eight-year-old director of "Reality Bites," wanted to make “a movie about personal relationships,” not define a generation that didn’t “want to be pigeonholed as Generation X.” Stiller’s forty-nine-year-old producer, Michael Shamberg, however, admitted he sought a sequel to his defining yuppie movie from 1983, "The Big Chill."

Bored, shiftless drifters played much better in short bursts on TV. As the 1990s began, The Cosby Show’s warm fuzzy family franchise ended, as did "Cheers’s" warm fuzzy community franchise. “There’s room on TV for a dysfunctional family you can laugh at,” said Matt Groening, the cartoonist who created America’s first successful prime-time cartoon since "The Flintstones." Television publicized the American dystopia with crude, cynical, selfish characters modeling the New Nihilism. "The Simpsons" inverted the Donna Reed–Brady Bunch squareness of Nick at Nite. Instead, the central character Bart, an anagram for Brat, reveled in being an obnoxious, defiant ten-year-old. His sister Lisa would call her brother, “the spawn of every shrieking commercial, every brain-rotting soda pop, every teacher who cares less about young minds than about cashing their big, fat paychecks.”

By 1994, the show, which debuted on the new Fox network in December 1989, was already a monster hit, confirming conservative fears that Hollywood hated America. With “Bartmania” unleashed, 1 million T-shirts a day sporting Bart’s image and hostile catchphrases like “eat my shorts” were being sold. By 1998, Time would designate Bart “one of the 100 most important people of the 20th century,” epitomizing this century of “change” more than Mickey Mouse, Superman, or Bugs Bunny.

In March 1993, two teenage Bart-like cartoon characters debuted, Beavis and Butt-head. In their snide, scatological world, Principal McVicker was “McDicker,” and the Secret Service was “the secret cervix.” While watching a Nirvana video, Butt-head wondered: “Is this, like, ‘Grudge’ music?” When Beavis then asks where Seattle is, Butt-head replies: “It’s this place where, like, stuff is, like, really cool.” One critic sighed, “Compared with these Bozos, Bart Simpson is Bill Moyers.” During Senate hearings in 1993, Senator Fritz Hollings, a South Carolina Democrat denouncing TV’s violence and vulgarity, sputtered about “Buffcoat and Beaver”—which only encouraged Mike Judge and his writer colleagues.

Next, this new American nightmare showcased grown-ups as cases of arrested development. By 1994, "Seinfeld" was emerging as one of the decade’s dominant sitcoms. A show about “nothing,” whose creators vowed “no hugging, no learning,” meaning no Cosbyesque moralistic epiphanies, "Seinfeld" reveled in its nihilistic self-absorption. In one breakthrough episode, the four friends competed to see who could resist pleasuring themselves the longest, popularizing a new phrase, “master of my domain.” A few months later, Jerry Seinfeld kept denying rumors he was gay, just “because I’m single, I’m thin and I’m neat.” He and George preserved their credentials as hip New Yorkers by injecting another catchphrase into the culture, insisting, “Not that there’s anything wrong with it.” If “The Contest,” by mocking one social taboo, moved America further toward becoming the Republic of Nothing, with no standards, “The Outing,” telegraphing tolerance, helped spawn the Republic of Everything. Despite their best efforts, Jerry Seinfeld and his partner Larry David were shaping society, teaching millions how to speak “Seinlanguage.”

Although very much the New Yorker starring in this New York–set show filmed in Los Angeles, Seinfeld would call Seattle “my favorite city. It’s the first place anyone ever liked me,” having had his first sold-out show there in 1983. “I feel like I owe my whole career to Seattle.”

Seattle Capitalism As Computer Capitalism

Seattle was sophisticated enough to appreciate Seinfeld’s wryness because it comprised more than the disaffected flannel-shirt-and-work-boots crowd. Its mix of progressivism and capitalism appealed to high-tech entrepreneurs like Bill Gates of Microsoft. He was raised in Seattle as an accident of birth; he returned to the large suburb of Bellevue in 1979 on purpose.

In 1986, Microsoft moved to its corporate campus in Redmond, Washington, shortly before its stock went public, and a year before Gates became the world’s youngest billionaire. The Microsoft “campus” would soon encompass 8 million square feet, housing most of this computer company’s 94,000 employees in Washington State. Seattle capitalism, like Silicon Valley capitalism, was a peculiar form of post-1960s’ Baby Boomer computer capitalism. In-your-face, elbow-your-competitors-to-the-side energy came wrapped in down vests, free lunches, snacks galore, and a worship of the great outdoors when not sleeping off another all-nighter.

Beyond its high-tech appeal, Seattle was America’s dominant coffee town, what David Brooks would call a “latte town,” as obsessive about downscale alternative status symbols as Wasps were about classic signs of success. Some attributed the city’s coffee obsession to the perpetually gray weather that left people craving caffeine. Soon, the whole country would be speaking about macchiatos and mochaccinos, dolce lattes, and frappucinos, served by baristas tall, grande, or venti, thanks to Starbucks, the coffeehouse behemoth.

In 1971, the first Starbucks store opened in Seattle’s Pike Place Market. In 1982, a Brooklyn-born kid named Howard Schultz joined the company’s small marketing department. By 1987, Schultz had raised $3.8 million to buy out the founders, having divined in Milan that a more robust coffeehouse culture could build community. The coffee bar could become a third haven in a new, individuated, secularized America, beyond home and office, replacing churches, general stores, and community centers. More Ben and Jerry than Rockefeller or Carnegie, Schultz pitched “the Starbucks Experience” as “an affordable necessity” not an “affordable luxury,” claiming: “We are all hungry for community.” Typically, this “community” was as virtual as “friends” would be on Facebook, reflecting parallel play not personal engagement.

Combining McDonald’s-type standardization and accessibility with Chivas Regal quality and indulgence worked. Customizing as many as 87,000 different drink combinations also appealed to Americans’ urge to individuate. By 1994, two years after a successful IPO, there were 425 stores. Two years later, there were 1,000 stores, with openings in Japan and Singapore. By 2012, 200,000 “partners,” meaning baristas enjoying stock options and health benefits, worked in 17,651 stores in 60 countries serving over 60 million visitors weekly.

Entrepreneurs loved this mix of creative energy, well-educated employees, a growing stock of Microsoft alumni, and Washington State’s small population size, limiting the number of sales-tax-vulnerable customers for an Internet shopping company. Another virtual pioneer lured west, Jeff Bezos, was a Texas-born wunderkind working in finance in New York who noticed that the World Wide Web increased its activity by an astounding factor of 2,300 from January 1993 to January 1994. He analyzed twenty different products, speculating how selling via the Internet could boost their sales. Bezos realized that offering titles without carrying inventory could outdo any bookstore. He arrived in Seattle in July 1994 and soon started calling his site “Amazon,” hoping that the Earth’s “biggest river” would inspire the launching of “Earth’s biggest bookstore.” Eventually, the king of Internet retailing would start planning “the everything store.”

Voluntary Simplicity or Stuck in Second Gear?

As Baby Boomers like Bill Gates, Howard Schultz, and Jeff Bezos helped the nation’s economy boom, many of their peers felt overwhelmed by America’s ever-growing thirst for money. In 1994, the economy soared with gross domestic product growth of 4.1 percent creating 3.3 million new jobs, the most since 1984. In 1992 Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin coauthored a book that became a blockbuster, "Your Money or Your Life." The authors advised finding meaningful work while reducing consumption. Robin began running workshops showing people how to manage money amid everyone’s overspending. Cecile Andrews’s workshops on “Voluntary Simplicity” emphasized managing time better amid everyone’s over-programming. And Janet Luhrs, a recovering lawyer and single mother, started "Simple Living: The Journal of Voluntary Simplicity" in 1992, offering fifty ways to date, cook, vacation, and enjoy life without spending money. With 15 percent of America’s 77 million Baby Boomers supposedly ready to join their movement, the three made Seattle the center of American simplicity. They combined the growing self-help ethos with a New Age sensibility and some good old-fashioned Social Gospel to heal from corporate burnout, overconsumption, and undersatisfaction.

Echoing the Puritans, the Quakers, the Transcendentalists, and the Hippies, the Seattle Simplifiers helped publicize Mathis Wackernagel’s and William Rees’s 1995 book "Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth." Noting that Americans consumed at least three times more than citizens in other countries, this work influenced Al Gore, who warned of America’s outsized and toxic “carbon footprint.”

The Seattle Sensibility Popularized and Nationalized

Even with this ambivalence, Seattle was starting to smell of new money, not just teen spirit. The instinct of "Frasier’s" producers to move the snooty psychiatrist of "Cheers" from his fictional perch in Boston to Seattle in 1993 proved correct. Wanting distance from "Cheers," they first chose Denver, but disliked Colorado conservatives’ attacks against gays. Instead, Seattle “seemed like this wonderful, tolerant, idiosyncratic place full of smart people.”

Dr. Frasier Crane and his equally pompous brother, Niles, occupied a rarefied Seattle of high culture and haute cuisine, with the requisite coffee hangout, Café Nervosa. When Niles doubted a neighborhood’s safety, the Cranes’ tough retired cop father snapped, “Oh, Niles, to you a sketchy neighborhood is when the cheese shop doesn’t have valet parking.” The kooky class dynamics delighted audiences. On September 11, 1994, the writer-producers David Angell, Peter Casey, and David Lee won an Emmy for their writing and Kelsey Grammer won for his acting as the show was honored as Outstanding Comedy Series.

Seattle became, in the words of the Seattle Times TV critic, “condo by condo… a lot like "Frasier."” “Microsofties,” flush with cash, told brokers “they wanted that cosmopolitan feel of ‘Frasier.’” The city became slicker, with million-dollar condominiums popping up on Queen Anne Hill and fancy fashion shops next to fine wine stores on Sixth Avenue.

While "Frasier" glamorized Seattle, another television phenomenon, "Friends," which debuted in September 1994 and ran for ten seasons, tamed, popularized, and nationalized the Seattle sensibility, this time in a New York City setting. The six slackers, bossy Monica, flaky Phoebe, spoiled Rachel, geeky Ross, goofy Chandler, and dumb but sexy Joey, are better dressed, cleaner-cut, and live in fancier apartments than their Seattle grunge peers, despite only having McJobs. They hang out endlessly at their coffee shop, Central Perk. In TV-land, all this twentysomething shiftlessness became clean and lovable.

Friends was a cultural phenomenon, affecting Americans’ speech patterns and attitudes: Joey’s leering “How you doin’?”; Ross’s plaintive “We were on a break”; Janice’s—Chandler’s first girlfriend’s—nasal “Oh my gawd”; and Phoebe’s unmelodic, “Smelly Cat.” "Friends’" world was youth-centered and self-centered, pampered by prosperity. As childish as they were—“always stuck in second gear,” the theme song suggested—their spoiled, self-indulgent Baby Boomer parents were more immature, especially the dads, a situation paralleled in other shows including "Beverly Hills, 90210," "Home Improvement," and "The Simpsons." If "Seinfeld" still had Baby Boomer baggage, with that gang’s selfishness edgier and guiltier, "Friends" offered a Gen X selfishness with fewer boundaries, without even the veneer of angst.

Excerpted from "The Age of Clinton: America in the 1990s" by Gil Troy. Copyright © 2015 by the author and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

Shares