HitFix television critic Alan Sepinwall is, to use the parlance of fellow critic David Sims, “the king of our industry.” Sepinwall essentially invented modern television criticism–writing some of the first post-air recaps ever on his blog What’s Alan Watching and as a columnist at the New Jersey Star-Ledger. In 2012, Sepinwall brought together his nearly 20 years of television experience to bear on what we now call the golden age of the medium, with his book “The Revolution Was Televised.” The book chronicles the behind-the-scenes development and cultural impact of a dozen shows, starting with “Buffy: The Vampire Slayer” and going through “The Sopranos,” “Lost,” “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad.”

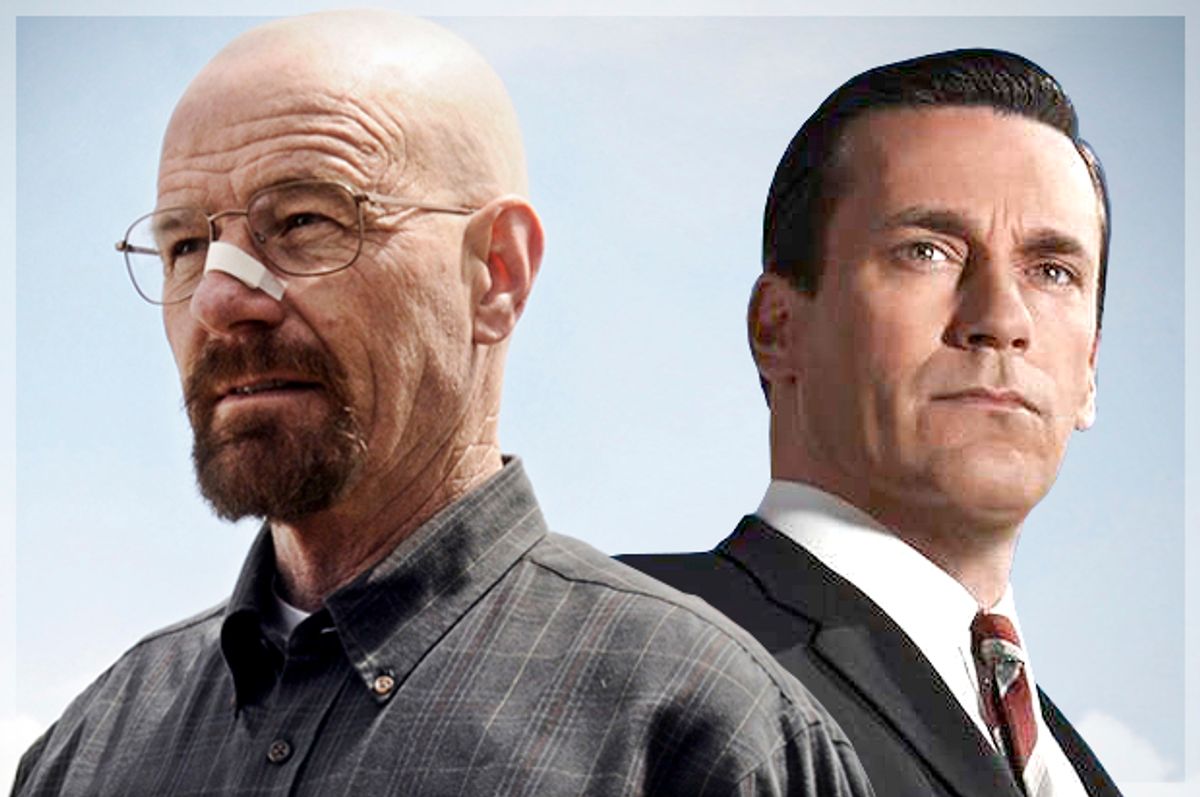

The last two shows, though, were still airing new episodes when Sepinwall published. So this month he’s published a second edition, which includes not just expanded and completed chapters on “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” but an extra epilogue that adds thoughts on our current era of peak television. I sat down with Alan to talk about those two controversial finales and the way these shows have wormed their way into our national dialogue. Read more below, and if you’re interested in getting the book, click here.

You knew you were going to have to come back and do finishing touches on both “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” because the finale was still in the future. So, now that that has happened, do you feel like you’ve made the definitive book about this era on TV?

[Laughs.] I like to think so. There’s a lot of story to cover. There are arguments to be made that there are other shows that could’ve been written about, that were taking place around the time of “The Sopranos,” “Deadwood,” and other early shows. Or other shows, circa “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” that maybe could be included. But I felt that these 12 shows illustrated different aspects of the ways in which we got to peak TV in America.

There is always this misconception about this book, in that it is saying, “Look, here are the best 12 dramas ever made,” and it is not that. I love “24,” but it is not one of the greatest 12 every made. But, it was notable in terms of TV’s transition into the hardcore serialization we are in right now. That’s why that’s there. There were other shows I could’ve included, but these 12 cover pretty much all of it, and I’ve now completed their stories… unless David Milch ever gets those “Deadwood” movies made.

Both “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” got a mainstream audience into prestige TV—in a way that has changed the way everyone talks about TV. I think those are the two that became pop-cultural phenomena, outside of, maybe, “The Sopranos.” Can you talk to me about that?

I agree with that. I think part of that is because the Internet was less of a big deal for most of the time “The Sopranos” was on. The way TV was written about was different. I didn’t wind up recapping every episode of “The Sopranos” until the last like, couple of years of that show. Whereas by the time “Mad Men” debuted, episode-by-episode recaps were a thing. There were just more ways to talk about TV, and more ways to analyze it. And at that point, the Internet was part of modern American life, and it had become part-and-parcel of the experience in a way that it wasn’t when “The Sopranos” or “The Wire” or “The Shield” were debuting.

So it’s interesting. These are both AMC shows, that both did what I find the kind of ridiculous model of splitting the final season into two pieces. And because there was so much investment in them, both finales were controversial in different ways. Do you think the way these two shows ended influenced your sense of where they belonged in the canon, or in your book?

Well, it’s been funny to watch how opinion on the two shows has really diverged, since the book was first published. I think, at the time, maybe if you were having an argument about what were the greatest dramas on TV ever, it would probably be some order of: “The Sopranos,” “The Wire,” “Mad Men,” “Breaking Bad.” Some people, like me, would argue for “Deadwood,” but you have a much harder time with that, because it ended abruptly. They were all on relatively the same level.

And then, I think, for a lot of people—“Breaking Bad,” that last stretch, especially, really elevated it in a way where it’s thought of more highly than it was at the time I was writing the book. Whereas a lot of people had become frustrated or bored with “Mad Men” at the end of it, which is a shame. As a result, that final season became—not quite an afterthought, but certainly there was not the hype and hullabaloo—and certainly not the ratings of “Breaking Bad. “

But also, “Mad Men” was a longer running show. It started before “Breaking Bad,” and finished after it.

Yes, that’s exactly right. And I also think that while the season split for “Breaking Bad” was annoying on some level, that was a show that was structured in a way where they could do that. You could have the cliffhanger with Hank reading the book at the toilet and you could wait a year to find out how they deal with that. So, that was maddening, but also kind of exciting. “Mad Men’s" not built that way. So all that meant was that Matt Weiner had to do two half-seasons of “Mad Men,” and we know from watching previous full-length seasons of “Mad Men”—“Mad Men” takes a while to ramp up every year! So, there wasn’t any room, and it kept clearing its throat over and over, and rushing at the end of those last episodes of seasons 7a and 7b. They were great, but we could’ve had more if he hadn’t had to start and stop twice.

Do you think season splitting is OK for some shows, and not others? I’m sort of anti- the idea at all times.

I think it did work for “Breaking Bad.” In general, I think, it is a BS thing. It is just a way to prolong the experience, and usually, not having to pay the actors any more money, which is why they call it a split season instead of two seasons. Most contracts have raises built in for each new season.

But, in “Breaking Bad,” they shut down production in between. So, it was in everything but name, two seasons. Whereas in “Mad Men,” they shot that final season all at once. They wrote it. They shot it. They were done. You had seven episodes sitting on the shelf at AMC for a year.

It does speak to how attached people became to these shows. One of the things you say in the epilogue, which I loved, is that “TVs biggest strength is time.” I think on AMC’s part, it was a power play, in some ways, to prolong those last two years for people to get two more years of the experience.

And I heard some people make the argument that this is AMC’s way of finally getting Jon Hamm the Emmy. He did finally win an Emmy, and I am glad about that, but I think it had more to do with the change in the voting rules than anything else.

You take a very journalistic approach to the book. You talk so much about the process behind both of these, and you interview the creators and the actors to get the whole story. But I am sort of curious about how you feel about both of those shows. How did you feel about the way “Mad Men” ended, versus the way “Breaking Bad” ended?

I am largely positive on both, while having some reservations. In “Breaking Bad,” there is a very strong argument to be made that the show should’ve ended with “Ozymandias.” One of the reasons I am most happy I did the follow-up [laughs] is because I got Vince Gilligan to basically admit the same thing. He says the only argument in favor of doing those two extra episodes is the scene in the finale where Walt admits he did it for himself. It is a hugely important scene, and the series needs that. But overall, I just like the note of absolute despair at the end of “Ozymandias” better than I do Walt having one last Pyrrhic victory in “Felina,”although I think “Felina” is a good episode as well. So, I feel a little ambiguous there.

And with “Mad Men,” it comes down to how I feel about the Coca-Cola ad. I go into that quite a bit in the book. It’s just—I wish we could have seen even just five seconds of Don back in New York, so the series wasn’t just saying that the sum total of his journey was that he was able to write the best ad of all time.

Weiner’s argument is, “Well, if you love advertising, then, you know, this is an awesome ending.” And… I don’t feel that way, even though I’ve been watching a show about an adman. I am not opposed to the idea that Don is going to come out of this writing a better ad and staying in advertising, because that feels true to Don. But, I don’t know—at the same time, it is the way in which he structures the whole journey of years and thousands of miles, and he divests himself of everything—and then the visual language of the finale tells you that, ultimately, the only thing that mattered was the Coke ad. It is not a dishonest ending for the series or for the character, but it is not necessarily the one I wanted, because, you know, I just wanted to see Don and Peggy together again, even though we got them on the phone.

Both shows have a sense of ownership over the ending, which you don’t get normally in TV. It’s more common now with prestige fare, but the medium has been historically in the service of so many business interests. In some ways, the dissatisfaction with the ending comes with TV not being that well-suited to endings. What do you think about that?

That’s funny you mention that. The book I’m working on now, with Matt [Zoller] Seitz—I was working on the intro to "The Fugitive” the other day. The ending of “The Fugitive” is one of the highest-rated episodes on television ever, and the producers had to fight to be allowed to make it. The executives at ABC were like, “Well, nobody cares, they don’t need to know how the story ends, they’ll just move on to something else.” The producers literally had to go straight to the advertisers and say, “If we do this, will you give us the money for it?” And as a result they proved that the audience does view these things as more than disposable.

But, endings are very hard. Like the ending of “Lost”: super controversial. “The Sopranos,” super controversial. The ending of “Battlestar Galactica.” A bunch of the shows in the book have divisive endings. But, then you have things like “The Shield,” which I’m able to show is so much better remembered because of that ending. It is still a great show otherwise. But it is a hall-of-fame show entirely because of that finale.

You could say the same thing about “Six Feet Under.”

[Damon Lindelof, “Lost” showrunner”] talks a lot about this in the “Lost” chapter. The TV show is this living organism. There is only so much of it that the author could control. Sometimes because of the business interests. Or because actors die, or actors leave, or this idea didn’t work, or that idea didn’t work. The plan that you might have had once upon a time is no longer valid, and now, you gotta scramble.

In your words, why do the endings matter so much to people?

Endings matter, because of the power of time. Because you put an investment into this. You put an investment to both the characters and the story. And you spend years of your lives watching them, assuming you watched them in a linear fashion. The minimum you’d spend is dozens of hours watching these shows. And so you want to see it end right.

And ending right doesn’t necessarily mean ending happy. Nobody wanted a happy ending to “Breaking Bad.” There are about 17 different ways they could’ve ended that show and it would’ve all been satisfying. But, like Walt riding off into the sunset, like, in a Lamborghini, and Skyler sitting a passenger seat smiling, that wouldn’t have worked.

You want to feel like, I’m glad this worked out, and I am glad I watched it from beginning to end, as opposed to, I watched the show and suddenly Dexter is a lumberjack. So, you have that phenomenon. The people who drove Lindelof off of Twitter would keep telling him, Thanks for wasting six years of my life, asshole. It doesn’t matter that they had tremendous enjoyment for a lot of those six years. They are just so upset about the ending that they can’t look back.

I’ve felt that way about the “How I Met Your Mother” finale, but I’ve caught a few episodes and reruns from the early season, and be like, OK, these are still good. I will just try to ignore anything about the mother.

And you see this cherry-picking. I’ve seen the first half of “Battlestar Galactica” many times, and the third and fourth seasons, I’ve kind of avoided.

The afterlife of some of these shows is so much better than the experience of watching them at the time. Because the book was originally done in a relative rush, I didn’t have time to actually marathon each individual show. So, I did a lot of cherry-picking. I would watch a lot of premieres, I would watch a lot of finales—the memorable episodes, where I wanted to pull a quote or whatever, just to remind myself of something. So, I was not necessarily watching the Columbus Day episode of “The Sopranos,” or just some random mid-season episode of “The Shield,” where it is mainly procedural. That is the same way with “Lost”—now, I go back, and I just look at the good stuff—I’m going to watch “The Constant” again, or the one where they fix up the VW van from the Dharma Initiative. I can just avoid the ones I hated.

In the landscape of more and more TV, the label golden-age of TV for me is more valid when talking about this cherry-picked experience, and a little less valid for an individual show. Like, I can say, “Marvel’s Agents Of S.H.I.E.L.D.” did this incredible episode, but I don’t know that I would necessarily say the show is all that good.

Yeah, I agree with that! I don’t know if you’ve seen the thing I wrote a couple of weeks ago, “In defense of the episode,” but one of the things that is kind of bugging me is how the Netflix shows—and all those shows that want to be on Netflix—have stopped making satisfying individual episodes, and it is just, “Here are 13 episodes of stuff. Sequenced chronologically.” This can sometimes be very interesting, but I never want to go back and revisit those shows—whereas “Lost,” “Mad Men,” “Breaking Bad” or “The Sopranos,” there are individual hours I would want to watch, regardless of the context of the other ones. If I’m going to rewatch “The Wire,” I am going to watch a whole season, and it is great enough to rewatch again and again. But “House Of Cards” sure ain’t.

It’s funny we’re even talking about this, because the phenomenon of rewatching is not on people’s mind right now because there are so many new things.

[Laughs.] Yeah, no. There are so many new things. But, I think this is probably an age thing, I grew up watching repeats. This was a big part of the TV experience. So I like revisiting old shows when I have the time, which is harder than ever to do. But, it is certainly a thing for when you’re cooking, cleaning, or when you’re in the mood, like, I just really, really want to rewatch Desmond calling up Penny again.

A lot of the networks, too, on an off-week would play a really good episode. When I was getting into “The West Wing,” NBC would play “In Excelsis Deo,” and that was the first episode I saw, and it hooked me. I was watching the best hour of that season. The landscape now is much more crowded, and much more focused on the horizon of the new.

That’s true, but, one of the other interesting aspects of peak TV is that for people who do not do what you and I do for a living, and therefore, like, aren’t watching the very best shows as they’re airing, they do not have the 400 shows that [FX head John] Landgraf talks about in a year. They have now an easy push-button access of the best of every show ever made, practically.

So, every day, there is somebody new watching “The Wire.” I get tweets all the time from people saying, “Thanks for turning me on to ‘Terriers.’ Man, I wish I’d seen that when it was on the air.” For those people, they are not reruns. They are new episodes.

What is a show or two that you’re excited about now, and might be in the 10-years-from-now “Revolution Was Televised, Part Two”?

If I was doing a book in 20 years about shows circa 2015, “Louie” would be in there. “Girls” would probably be in there. “Orange Is the New Black,” and maybe another Netflix show, would be in there. “Transparent,” “Game of Thrones,” would be in there. “The Walking Dead” would probably be in there, assuming I could get anyone on the show to speak to me, after all the things I’ve written about Glenn.

It would be about the shows that are reflecting the transformation in what’s happening TV right now. A lot of that has to do with streaming, a lot of that has to do with the move to independent filmmaking, with even more of an auteur approach like “Louie” or “The Knick,” I would have “The Knick” in there. I would talk to [Steven] Soderbergh. With “Game of Thrones” or “Walking Dead,” you would look at the blockbuster phenomenon, and the idea of using sci-fi and fantasy on this big scale to bring it to audiences in a way that dwarfs anything vintage shows like “Mad Men” were doing.

I like to think about shows that have been around for some years to get a bigger sense of what they’ve done, and what influence they’ve had. You could see the impact with “Louie” and with “Girls.” You can see the impact “Orange Is the New Black” has had in terms on increasing representation on TV. “Empire” might be an interesting show to deal with. Certainly, there is no disguising the fact that my book is largely about shows about middle-aged white guys. That what was being made, and that was being acclaimed. And one of the best things that has happened is that we are starting to get more diversity of representation. It is not perfect, and you know that as well as I do, but it’s still better. A show like “Orange Is the New Black” wouldn’t have existed 10 years ago. For “Transparent,” no one would’ve built a show around Maura Pfefferman as a star. She would’ve been a Very Special guest star in one episode of the show, and she either would’ve been there for the main character to learn a lesson about his own intolerance—or would’ve been there as the butt of the joke.

Given all the copycats and what we’re both seeing as a kind of cherry-picked landscape of good TV, do you think we’ve exhausted the limits of what TV can do?

No, I don’t think we’ve exhausted the limits at all! I talked to Jill Soloway about this the other day, about “Transparent” Season 2. I think one of the reasons I am so frustrated now with the streaming shows is because it’s still a new art form. This idea of the 13-hour or 10-hour or five-hour season as a storytelling unit, as opposed to the individual episode, this is new, and everyone is still figuring that out. I think we will reach a point in which experiences become more satisfying that they are now, where you can actually do one big story blob, and it doesn’t feel like it’s dragging in spots.

There are so many more storytelling options. There are so many more voices that haven’t been heard or only heard a little bit like "Fresh off the Boat.” That’s a really good show telling, in broad strokes, very familiar sitcom family stories, and because it is filtered through this specific perspective, it feels like something brand-new. There are more of those options. More and more of those opportunities for someone to come in and do, for example, a Muslim American family show. Someone is going to do that. And there is going to be pushback. And it’s probably going to be on premium cable or something, but that is coming, hopefully in the next five years.

Shares