From the start of "Only Love Can Break Your Heart," Ed Tarkington makes clear that two things are happening at once in this debut novel: a coming-of-age story beset with the common trials of growing up, and a larger-than-life drama of intimacy and betrayal.

In the opening chapter, we meet Rocky, the 8-year-old narrator, and his idol, his 16-year-old half-brother, Paul. In those same first pages, we get mysterious gunfire, a haunted house and talk between kids of “liquor, poker, and whores.” This is precisely the kind of thing I want to read in the winter, when the world has gone cold and gray and quiet. Somebody’s got to stir things up.

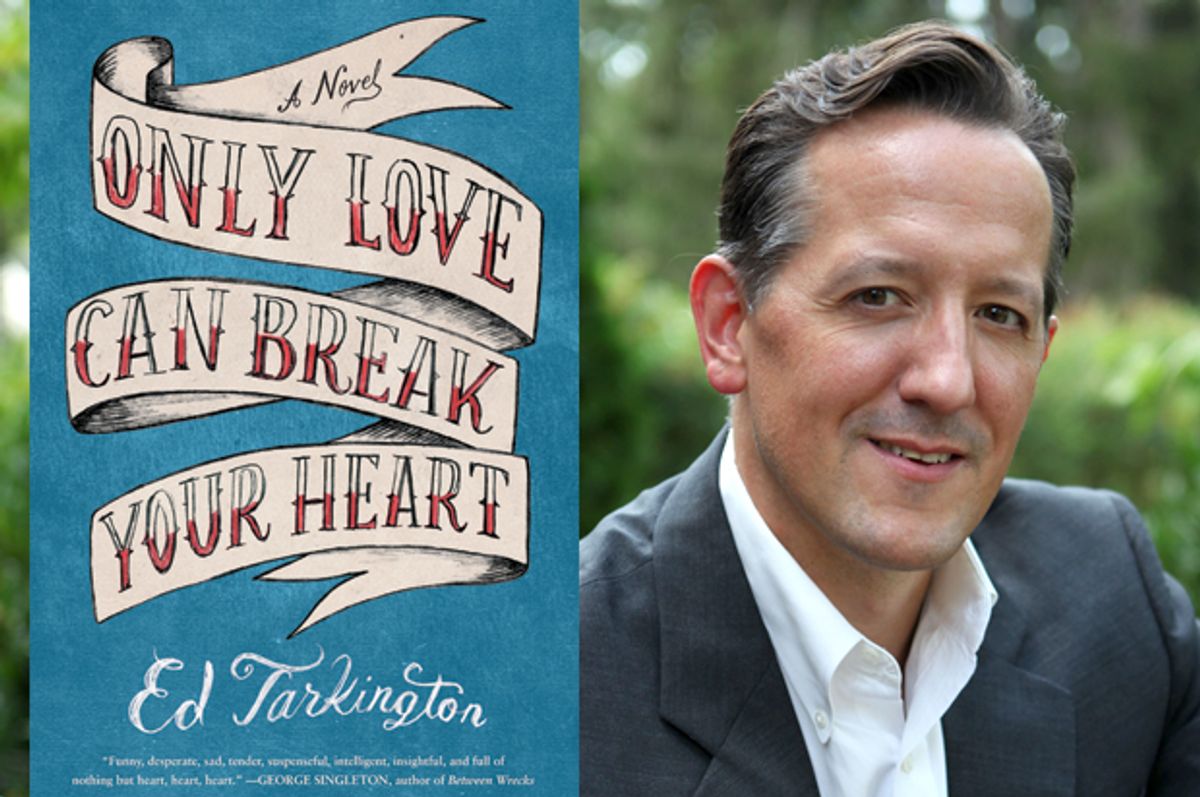

Tarkington has created a sensational page-turner with a literary feel, a blend that’s remarkable but perhaps not surprising when you consider the balance he strikes in his own life. A high school English teacher at Nashville’s all-boys Montgomery Bell Academy, he is “Dr. Tarkington” by day. At home, he’s a husband and dad of two young daughters. And in that way in which only the most die-hard pursuers of a dream can wring extra minutes out of the day, he’s a member of Nashville’s creative community who shows up at literary festivals, music shows and — most important — his desk, where he writes every day. He, too, is many things at once.

The epigraph — “How accidentally a fate is made . . . or how accidental it all may seem when it is inescapable” — comes from "The Human Stain." Why that passage?

I’ve always been fascinated in art and life with how random circumstances can direct our paths. These characters make some pretty reckless choices when they’re young and have to watch the consequences of those choices roll out from there. But when we come to the end of their story, we discover that this was the only way it was ever going to be — all of this had to happen. I thought that line elegantly captured that conundrum.

It’s perfect for that. Thanks, Philip Roth.

I like epigraphs. Even if I’m not going to keep it, I always try to start with one in order to get a theme or a tone in my mind as I write. I try not to think too much in advance about theme, because you know — you get pedantic if you think too much about it. But I want to start out thinking about mood and what’s really at stake in the story.

Do you outline before you start writing, too?

I don’t carefully outline in detail, but I need a general outline. Some writers — like John Irving, who’s one of my heroes — spend a year on an outline before they start writing. Walker Percy, on the other hand, would just start writing and let the story unfold before him. I have to be somewhere in between — that’s the way it goes for me. I need to know where I’m going, but leave enough undecided so there’s a process of discovery involved.

Let’s talk about how "Only Love Can Break Your Heart" began for you. Did you start with a character or a scene?

Well, when I wrote this book, I was at sort of a crux in my writing life. I’d written another one before this, which I’d worked on a long time and had great hopes for, and it hadn’t sold. I was getting kind of worried that maybe this dream wasn’t doing to come true after I’d put so much effort and so many years into trying to mature as a writer and really do this thing. So when I started this second book, I thought, this is it. I’m going to take a real hard shot at this one more time. When I was younger I used to feel like I needed to “save up” ideas for later. But it finally hit me that this is later. It’s time. I wanted to throw everything in there.

How long did it take you to write?

It took me almost seven years to write the first one. This one I wrote in less than two.

Why so much faster?

It’s based so much in memory, instead of research. And life is less complicated now. My kids are far enough along to have more of a routine, and I have more time to write. And a lot of these things have simmered in my mind forever. They’re things that happened to me or that happened in the town where I grew up as a kid.

And that’s the town you’ve re-created somewhat as 1970s “Spencerville”?

Yes, I wanted that town to be like a real place — Lynchburg, Virginia, where I grew up — but not actually be that place. So I played around with the details and changed things up a bit. People who grew up where I did and when I did will see a lot that they recognize there, still.

Would you say there’s some of you in Rocky?

Definitely. I mean, I don’t have a brother, but I do have a half-sister. In a lot of ways, Rocky’s looking at Paul the way I used to look at her, and Paul’s problems are her problems. The part of my history that is the real genesis of the novel is the gradual process of disillusionment I went through as I got older and began to realize that my sister — whom I adored — had serious mental issues. The way for me to avoid writing a memoir was to flip the gender and imagine a bunch of other conflicts. But the core problem of the half-sibling who can’t ever quite get it right is based in truth.

So there’s more than just a vague notion of your history here. You’re drawing on some specifics.

It’s how I decided I wanted to be a writer, actually. My half-sister made multiple suicide attempts. She had a rough childhood. When I was about 10 years old I was at my friend’s house down the block, watching a movie in the basement, and my friend’s dad came down and said you have to go home. I asked why, but he wouldn’t tell me. When I got home, my mom told me my sister was in the hospital, that she had tried to kill herself by swallowing a whole bottle of Extra-Strength Tylenol.

My dad was sitting there — one of his best friends had his arm around him — and he was crying. I’d never seen him cry before, he was one of those tough-guy types, you know? I was scared to death. It shook me to the core. Before that I thought he was invincible, that he couldn’t feel that kind of fear or that depth of pain. It was a formative moment.

From then on, I had this urge to try to write about what was going on in my family and tell stories about it and come to terms with it. So all that stuff has been right here for a long time. I’d been pushing it away because I didn’t want to write something that was autobiographical. And then I finally felt like I had enough distance and maturity to take these elements of my life and fictionalize them into something that wasn’t a true story.

It’s not memoir, but it’s fiction with a lot of memory in it.

Right. I had to overcome this fear that maybe this material wasn’t “serious” enough, because it’s just about these quirky people in this small Southern town, instead of about something really topical and heavy, like war or terrorism. But the more I thought about it, I felt like the stuff I wanted to write about — the ordeals so many families experience, love and all its complications, the toll of mental and physical illness — these are subjects I take very seriously, and I think a lot of other people do too.

When you’re writing a scene between two characters, do you try to err on the side of keeping things totally plausible, or do you say, "YEAH, this is fiction!” and go for it?

I pretty much go for it.

I thought that’s what you’d say.

[Laughs] I mean, this is one of those things that’s talked about all the time in writing workshops. Time and again, some story comes up in workshop and someone will complain, “That would never happen,” and then someone else will raise a hand and say, “Actually, that happened to me.” But it doesn’t matter whether it’s a true story; it matters whether you can make people believe it’s true.

I don’t feel particularly restricted by the fear that a really seemingly fantastic detail won’t be believable. I just have to work harder to bring it across. Nothing that happens in this book hasn’t happened to somebody. The trick is, how do I make it believable?

You’ve done it, don’t you think?

I hope so. Only the reader can decide that. In fact, one of the parts of the book that might seem like the biggest stretch — the murder — is rooted in fact.

What?

Yes. When I was very young, an older couple who lived just outside Lynchburg were brutally stabbed to death in their home. A young woman who was a family friend of ours and a former schoolmate of my half-sister’s became a suspect. My mother was actually interviewed by detectives about a pair of shoes she’d once loaned to the girl when she attended a Bible study at our house, because the police thought they might be a match for a shoe-print found at the crime scene. We all felt profound fear and dread in the days after that murder. And then when the crimes were solved, the shock over who was responsible raised even more questions. So this dark episode served as the seed of a good story, but I was also able to use it to gesture to deeper themes of family and community, loyalty and betrayal, love and redemption.

Holy smokes, I had no idea. This is certainly not one of those books where the sentences are beautiful but nothing really happens. Is plot what you look for as a reader, too?

In contemporary literature, particularly of the more highbrow variety, there's this fear of plot. People feel like it’s not the real stuff. That it’s not intellectual.

Because literary fiction has to be 600 pages of subtle eye movements and inner thoughts, right?

Exactly. And I love some books like that — with a beautiful voice, that are more about the interior life of a character, without a lot of action. But most readers who aren’t also writers expect a good story. I didn’t decide to be a writer so I could impress college professors, even though I probably got distracted by that for a while. I wanted to be a writer because I wanted to impress people like me when I was younger, when I’d stay up late because I needed to know what was going to happen next. I want to be pinned to the chair when I read.

I read it over the course of a day and a half, and I kept intending to put it down, but then I’d want to read just one more page, one more chapter, one more hour.

That’s good to hear! That’s what I was going for. Which is not to say I don’t care about the other things — the sentences and the characters. But at the same time, it’s the big moments in life that we’re drawn back to. So I thought, let’s go big and see what happens.

I was folding down pages whenever I spotted a literary reference or a little wink to another book. I think even if I didn’t know you were an English teacher, I might have guessed.

Really?

When one of your characters mentioned the speeches of Huey Long, it got me thinking about Willie Stark and how much I loved "All the King’s Men" in high school. And it was the part of the book where Rocky was in high school. So just that tiny reference pulled me in closer to the story.

It does take you back — being a teacher takes me back, every day. Working with these teenagers, watching them discover the things that inspired me. Students get completely lit up by the same things that lit me up. People think teaching high school is a terrible job for a writer, because it’s so demanding and draws on the same resources as writing, which is true. But the job has been great for me. When you’re teaching at this level, you are reminded why this literature became important to you in the first place. You get trained again in how it works.

Is all of American literature trying to solve the same riddle? Is that why themes and arcs repeat in books across time? The small town, the weight of secrets, the loss of innocence ...

If we could answer that question, people would probably stop writing novels. [Laughs] Actually, I was thinking recently about Edgar Allan Poe and this essay he wrote called “The Philosophy of Composition.” He talks about “unity of effect” — how he uses effects like the haunted house, the damsel in distress, all those stock elements. And it’s true. I can look at everything I read and see the same things. "Beloved" by Toni Morrison is the great masterpiece of our time, and they’re all in there. It’s a ghost story.

Like you pointed out, these patterns exist in everything that’s successful. Books that are very different on the surface often come down to the same things, the same relationships. We’re all struggling with our demons and how the world works and why it doesn’t work the way we want it to.

Speaking of small towns: How long have you lived in Nashville?

We moved here eight years ago. You?

I was born here, but we moved away when I was little, and my family and I moved back a year and a half ago. Everyone talks about how much Nashville has changed in the last decade. Do you think there's some of that small-town vibe left here?

In pockets of it for sure. That’s one of the reason I like living in East Nashville. My life is one side of the river, and my job is on the other. I don’t like the idea of going out to the store on Saturday morning to pick up coffee in my pajama pants with my hair standing straight up and running into one of my students’ moms.

Nashville’s changed a lot recently, and people who’ve been here fewer years than I have already feel entitled to complain about it. But most of the changes have been for the better, I think. I’m not one of those people who’s like, “Agh, this town’s going to hell” because it’s growing so fast.

You’ve got to take the bad with the good, you know. I’ve never lived for a long time in a place that’s cool before — a place people want to move to. I like it. People here are nice. Even when they do get gossipy, they have good intentions.

And gossip is where stories come from.

Exactly. My dad traveled a lot, and I’m the only boy in the family. I was surrounded by women growing up, and they were always talking about what everyone else was doing. I’m always listening to those stories. All writers are gossips — airing everyone’s dirty laundry and then pretending they made it up.

What does the literary community here mean to you?

I was amazed when I got here. I had no idea I was going to fall into this vibrant community. There are a ton of writers in town. Ann Patchett is here. Lorrie Moore and Tony Earley are at Vanderbilt, along with a number of other acclaimed writers who are turning that MFA program into a heavy hitter. Humanities Tennessee does an amazing job with the Southern Festival of Books and with Chapter16. They’ve done wonderful things for me. And then of course there's the bookstore.

Parnassus Books! [High-five]

Parnassus changed the game in terms of driving literary activity and bringing writers to Nashville. Back in 2010, book culture in Nashville seemed like it was on life support. Then Ann [Patchett] and Karen [Hayes] got assertive and did something about it. It’s been amazing to see it turn completely the other way.

Other than New York, I can’t think of a more literary city in America right now. There are so many book events you couldn’t possibly get to them all. We’re so lucky that it’s that way here.

What section do you gravitate to first when you’re in the bookstore?

The kids section.

Really? Even if you don’t have the kids with you?

I usually do have them, because they’re my excuse to go to the bookstore. I can tell my wife, “I’m taking the kids for an hour,” and we go straight there. But if I don’t have them with me, I go to new fiction. I’ve always liked to see what’s new. But now, when I’m browsing, my approach is so different. When you know you have a book coming out, you’re curious about how it’s working for other people — where their books get placed, how their covers turned out, who’s blurbing whom.

Some of my favorite bookstores are used bookstores. When I lived in Charlottesville, Virginia, for instance, I’d spend hours getting lost in Heartwood Books on Elliewood Avenue, right by UVA. I don’t get to do that much anymore. I miss it.

Of course, here in Nashville, we're surrounded by storytelling in music, too. Have you ever done any songwriting?

Yeah, and I’m terrible at it. I was in bands in college. I was one of those people who thought I might really go that way for a while. Thank god I came to my senses. I have tremendous respect for the songwriters I know.

You're good buddies with singer-songwriter Will Hoge, right? How did you meet?

I’m glad you asked! One of the first things we figured out when we got to Nashville was preschool for our daughter. I realized within a week that all these kids in her class were the kids of parents in the music business. We called it rock 'n' roll preschool. Will was one of the dads. That was when “Even If It Breaks Your Heart” was all over the radio, which I consider to be one of the best songs of the past 10 years. So I knew of his music, and then our families started hanging out together and everybody hit it off. We get along great.

And he’s written new songs inspired by this book? How did that come about?

I’d just had my first big conversation with my marketing and publicity people at Algonquin, and we’d been brainstorming about what sort of things we could do to get the attention of booksellers when we sent out early copies of the book. There’s so much music in it, so we talked about maybe printing out a bunch of 45s, putting the book cover on some vinyls, just for quirky packaging.

That totally works, by the way.

Does it really?

Well, it doesn’t convince me that a book is any good; I still have to read it. But yeah, I’m a sucker for packaging. So when did Will come into the picture?

Well, I went home after that marketing meeting, and there were my wife, Elizabeth-Lee, and Will’s wife, Julia, in my kitchen having a glass of wine while the kids were playing. I started telling them about the record idea and they were like, “What are you going to put on it? Let’s get Will to do it!” I didn’t want to ask him, because I know it bugs musicians when people are constantly coming up and asking for favors — I didn’t want to do that. I try to respect the creative space of my friends. But at Julia’s urging, I asked him. I think I actually said, “I’d like to exploit your talent for my benefit.”

Honesty. Good approach.

Yeah! He said no problem. Then he read the book and he loved it. You’re always scared to death when people you know read your work — you don’t want them to have to pretend they like it. And now there’s this music that came from this story. He plays the songs at his shows now, and he plugs the book onstage. It blows my mind. He’s one of the most generous people I know. I’ll be forever grateful to him for doing that for me. We both agreed that no matter what happens, it’s been a cool experience for us to do something together. I’ll cherish that for the rest of my life.

This is a jackass question to ask while you’re basking in the glow of this freshly launched novel, but I’ll ask anyway: Are you working on another one yet?

I’m working hard. I don’t want to say too much. I actually was working on two novels for a while, but now I’m focusing on just one. I’m moving along at a real good clip right now.

A mutual friend of ours told me you worked on "Only Love Can Break Your Heart" by getting up at 4 a.m. every day and writing until it was time to get your kids up and head off to school yourself. Are you still doing that?

Well, I get up at 3:30, but I’m usually not awake until 4, if you know what I mean. And yeah, I still do it, mostly because that’s the only time in my house when it’s completely quiet, because everybody else is asleep. If I knock out 1,500 words in the morning, I can go about the rest of the day without feeling anxious. I’ve done my day’s work — as a writer, anyway.

I’m impressed.

It was hard at first. I’d never really been a morning person. First thing after I got out of bed, I’d go stand outside in the cold with a cup of coffee to wake up. That’s back when I was still smoking a little bit — so I’d smoke a cigarette, like, maybe this will help. And I’d picture my father, in heaven, laughing his ass off. It used to drive him crazy how late I’d sleep in as a kid. Saturday morning, I’d still be in bed at 10 a.m. and he would have been up for hours already. I’d come out and he’d be sitting at the kitchen table stewing over the fact that I was just getting up. Now look at me. He wins.

Writer Mary Laura Philpott is an essayist; the author of "Penguins With People Problems"; the founding editor of Musing for Parnassus Books; and the co-host of "A Word on Words" on Nashville Public Television. She lives in Nashville with her family.

Shares