When Conan O’Brien tried to get Hunter S. Thompson to appear on his talk show, the writer would only agree to a segment if they went to upstate New York to shoot guns and drink hard liquor. Featuring his most famous proclivities, firearms and whisky, it’s a classic Thompson moment, a television appearance dictated, like his life and like his death, entirely on his own terms. It’s an episode that adds to the Thompson myth, another treatment of him not as a person but as a persona—as a cultural icon whose behavior and success are so inextricably tied together that it’s impossible to understand one without the other. The way he lived was the way he wrote.

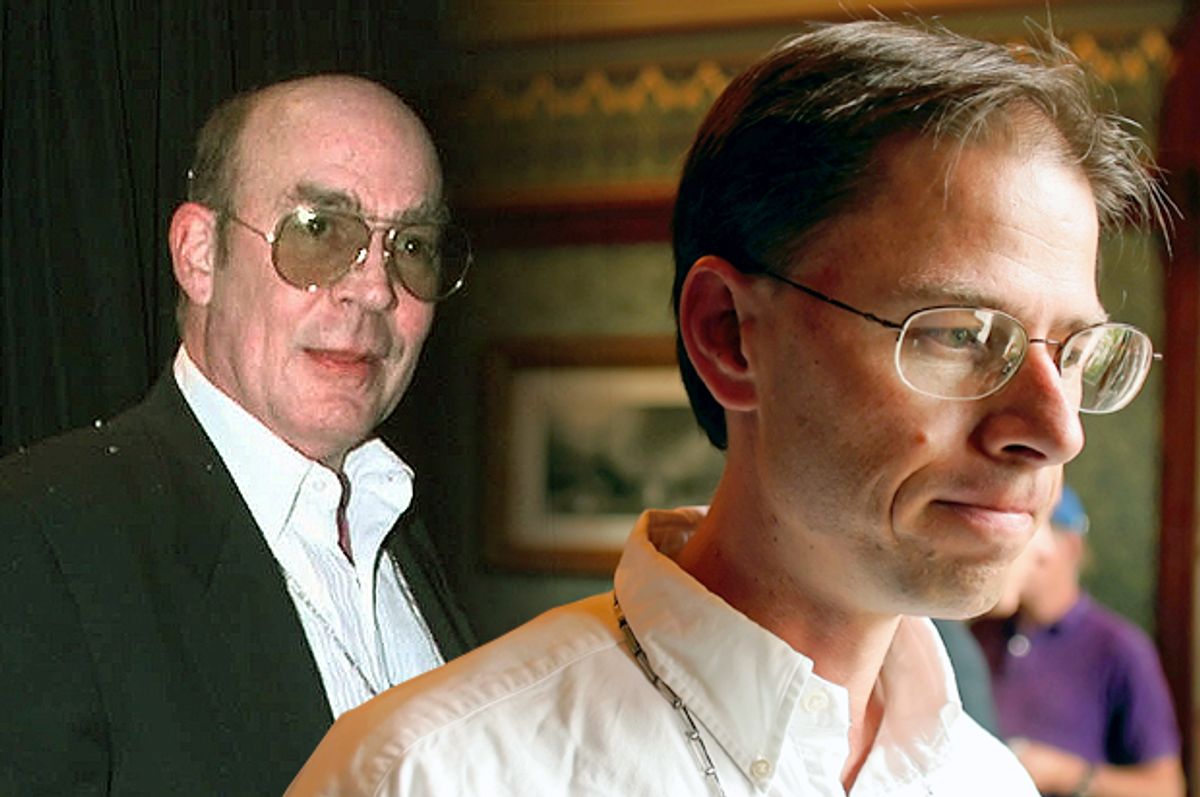

But, of course, Hunter wasn’t just a symbol of Gonzo journalism, and he wasn’t just a caricature of the ‘60s. He was a man—a flawed individual known for his bouts of extreme rage, for his unprovoked verbal eruptions, for his short days and long nights. Nobody experienced the unpredictable fits of anger more so than his only child. Arriving nearly a decade after Hunter’s suicide in February 2006, Juan F. Thompson’s new memoir, "Stories I Tell Myself," details the long path of reconciliation between a father and a son. It’s a journey of love and forgiveness, how one learns to accept a person when there’s no hope for change. It’s a portrait of Hunter as a human being, funny and fearful pages filled with drunk, smoky evenings, famous friends and admirers, extensive travels and financial uncertainty.

Relying on his memory, on what he considers sometimes “treacherous” and “unfaithful” and “perfidious,” Juan shares the 41 enthralling and scary years he had with Hunter: living in Woody Creek, Colorado, in a house stockpiled with guns, where ammo was stored in the kitchen cabinets; riding, as a young boy, on the back of speeding motorcycles; leaving his family and home state behind for a lonely and isolating East Coast school (twice). He starts with his own birth and ends with Hunter’s exorbitant funeral, when his dad’s ashes were shot out of a cannon.

This interview took place over the phone. It has been lightly edited for concision and clarity.

Why write the book now? It’s been almost a decade since Hunter’s death.

I just wrote an essay for Powell’s Books, for the store’s newsletter, and the essay is about why it took me nine years to write this book. I started in 2006, and, well, it took nine years. Why now? Because it took me nine years to write the damn book (laughs).

Were you sorting through his archives and his letters? Nine years is a long time.

A combination of things. First of all, I’d never written a full-length book, and I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

None of us do.

(laughs) Yeah, my God, my God. Part of it was simply time, too. I got a rough draft done in about a year, but then I realized that was the easy part, getting words down on paper—the basic skeleton. The hard part was pulling all these scraps together into a single, unified and compelling story with an actual arc.

And it was also just really difficult writing about my dad and my past. Much harder than I thought it would be. I figured it would be fairly straightforward and easy to remember, but it was an emotional and taxing process—and not one that I ever looked forward to doing. So I would take long breaks. There were times when I probably didn’t look at the manuscript for six months, and then I’d finally come back to it, and you know, see new things. What I was just writing about in this Powell’s essay was how it turned out that I really did need all of that time. If I had finished this book in a year, it wouldn’t have been a very good book. It would have been pretty one-dimensional. I was grieving. It would have been focused on how much I missed my dad and all the things I had heard about him. And it took years for me to reflect upon his life to realize that I needed to tell more of the story—and be fair. And ultimately, at the end of the day, I loved him, and I respected him. That’s where I ended up. But that doesn’t mean—he did do a lot of rotten things.

"Stories I Tell Myself" opens with a confession that you constructed the memoir based on memories, which are oftentimes unreliable. Even the title is a reference to this idea. Specifically, as a child, you were in situations that most kids never experience. I’m thinking about when Hunter brought you and your mother, Sandy, to hang out with Ken Kesey and the Hell’s Angels. Or even Jimmy Buffett’s wedding, a celebration you would later learn was filled with all sorts of drugs. Since you were young when both of these events occurred, you have had to rely on other people’s testimonials, and I’d imagine your own perception of your own childhood changed when, as an adult, you would hear all of these stories. In that way, you, like so many others, had to mythologize Hunter. Was it challenging understanding your father as a man and not just a persona, or a symbol?

I think part of it was reconciling with my father as a writer, as this caricature, and as the guy I grew up with, as my father. There’s truth in all of them. But I really needed that distance from his death. And I don’t know if I used these exact words in the book, but for those people close to Hunter, there was a very strong sense of loyalty. You have to protect Hunter. You have to be loyal to him. That was an imperative, and that was my first instinct in writing the book. Of course, I’ll protect him.

Were people loyal to him because they respected him, or was there also an element of fear? You describe, growing up, you were always afraid of him, too?

I think it was more that you didn’t question it. Not so much fear, if he did something wrong you would get in trouble. It was that he needs protecting, and our job is to protect him. And that took a while to realize that doesn’t really—now that he’s dead, I don’t really need to follow that obligation. It’s really up to me, and what I believe is important to tell rather than what he would have wanted me to say if he were alive. And that’s a huge factor. It would have been extremely difficult for me to write this book, much less publish it, if he were alive.

What do you think his response would have been if he were alive?

He would have been—I think, it’s so hard to tell what Hunter actually thought—horrified and angry and embarrassed. Because he would have had to deal with the consequences of that knowledge. But I really think—he always expected me to be honest. Once he was dead, and he didn’t have to deal with it, I thought: yeah, tell the truth, don’t cover it up. And I’d be doing him a disservice. I’d be failing in my task, if I were to continue to try to protect him, as we had always done. It wouldn’t be real.

In your memoir, you refer to both your father and your mother as Hunter and Sandy, respectively. Did you call your father “Hunter” throughout his whole life, and not "Dad"? Did you call your mother “Sandy,” and not "Mom"?

Yes, and I have no idea why. As long as I can remember, I always called them that. And I can only imagine it was because that’s how they referred to themselves. It must have been. I don’t think as a 2-year-old I decided that I’d call him Hunter, instead of Dad. Why they made that decision, I have no clue.

You ended up, despite all the craziness, pretty tame. You have a pretty normal life. You live in Colorado, you work in IT. Was being normal, for lack of a better word, a way to rebel?

I think so. At the time, it certainly wasn’t conscious or deliberate. I think it was a reaction against the uncertainty of the craziness. First of all, Hunter was a freelance writer, so there was no guaranteed income. My mom’s full-time job was taking care of Hunter and me until the divorce. So that was definitely a part of it, the financial uncertainty.

But secondly, as a kid and as a teenager, I knew I did not want to live like my father did. For the most part, I rejected the drugs and the drinking. And I think just by my nature, I’m not like him. He was just born that way. He was just born to be Hunter. I don’t think there’s anything in his upbringing—I don’t think, had things been different, he would have ended up an insurance agent like his father. That wouldn’t have happened.

He was just wired that way.

Yes. He was totally just wired that way.

You write a lot about how Hunter was a paradoxical individual. You mention that “one of the most difficult paradoxes in Hunter’s character was the presence of both a strong, genuine caring for others, and a profound self-centeredness.” And that, it was “so ironic that as a father Hunter passed on so few traditions, yet he possessed these traditional reflexes that would show themselves unexpectedly.” When you didn’t shake someone’s hand, for instance, he got upset, even though you had never been instructed on good manners. Is this what made him so unpredictable? That you didn’t know where he stood on certain issues?

Not so much that—he was just so volatile, and I think he became more so the older he got. As countless people will testify, he would erupt into a rage for the tiniest provocation. And that was really scary as a kid. And even as an adult, you don’t just get used to that. I learned to deal with it, I’d leave. But it was always uncomfortable, for sure.

Among swimming and watching movies, one ritual between you and Hunter was cleaning and shooting guns. He taught you how to respect the machines. They brought you together. What was it about firearms that produced such bonding moments?

I think it really could have been anything. But I enjoyed shooting guns, and obviously they were very important to Hunter. Cleaning guns needed to get done, in order to shoot them. It’s a manly kind of thing, and we shared the hobby. Without recognizing it, we probably seized on the opportunity: here’s something that we can do together, that can help connect us. So guns took on a greater importance because they provided a bonding ritual between us.

Did you always believe your father would kill himself with a gun? Ralph Steadman said Hunter told him, many years ago, that he’d pull the trigger at any moment. Were you just waiting for the day?

Yes. He had been clear for years and years and years that he was going to kill himself, and it would be with a gun.

There would have been no way to stop him, then?

I mean, how do you stop someone? He had threatened that he was planning to end his life before, and we talked him down. But one thing about Hunter, if he was going to do something, he was going to do it, and nobody was going to stop him. It was a very strange thing. I knew at some point he was going to kill himself. He was not going to go to the hospital. He was not going to go to a retirement home.

He hated the hospital, right?

Yeah. He hated any loss of control. The idea of Hunter in a nursing home—that’s just impossible. It would never happen. But boy, I didn’t expect his suicide when it happened. It was one of those things. It’ll occur at some point—at some point down the road, we’ll get the phone call that he had done it.

You didn’t expect to be there when he did it, you’re saying?

No. I sure didn’t expect it to be that weekend when I was visiting with my family. As I wrote, in retrospect, the signs were there, but I didn’t recognize them, and I’m not sure I even wanted to recognize them. Because if I had known what he was thinking, my God—what could I have possibly done?

You cleaned the .45 the day before Hunter used the gun to kill himself. When Hunter died, you, your wife, Jen, and your son, Will, were all in the house.

How did you feel about him implicitly making you a part of his suicide without your knowledge? Do you consider it a loving act?

I do—I think it was out of love, yes. I think that he wanted us there because he didn’t want to die alone. I don’t think he wanted to be found by strangers or the police. I think he wanted us to be there. He wanted me to be there, to make sure things were handled with respect—with how he wanted them to be handled.

That’s what I think was going through his mind, and I’m glad I was there, because it would have been much worse not knowing what had actually happened. But it was certainly not easy.

Again, it goes back to his paradoxical nature. I think it has a lot to do with his trust and love for me, and my wife, Jen, and my son, Will. And at the same time, I think it was a very selfish act. He just really didn’t think how this would affect us long term. I don’t think he thought it and disregarded it—he likely just didn’t think of it.

And you know, he was profoundly unhappy.

Hunter died at Owl Farm, his longtime home. Like him, you seem to have a deep connection to the place, to that house in Woody Creek, Colorado. Of course, that’s where you spent the most time as a kid, and there’s a certain level of comfort in the familiar. Also, Hunter clearly had a great community down the road in Aspen—in his early years, he held court at Jerome Bar, and when he slowed down, he had people shuffle through his kitchen—and Colorado flourished with the progressive ideas your parents supported, especially with experimental education. There, Hunter enjoyed his space to live how he wanted. But I see something perhaps deeper in your relationship to the place, to the land specifically. Did you feel a particular connection with your property? Maybe on a purely visceral or spiritual level? You kept returning to it, even after brief spurts of absence (boarding school, Tufts, and a semester abroad in England).

Owl Farm was where I grew up—it’s where I have my earliest memories. But it was also so much more than a house, because it was so important to Hunter. That was his base, his foundation. It was a place where he could do whatever he desired, and it was a place where he could always return. And there was space—which was why it was so strange, when I was a kid, and we spent that year in a colonial house in Washington, D.C. Hunter was on the campaign trail. We just didn’t belong in there.

That being said, why did you have such a desire to go to boarding school on the East Coast? Why, after the crushing loneliness you felt then, did you return to New England for college?

(laughs) Oh god.

I mean, I went to school in Boston, and I hated almost everything about that city. It’s so provincial and parochial. People from Boston really like Boston, and I still don’t know why.

(laughs) I know what you mean. I still ask myself, “what was I thinking?” There were so many other schools where I would have bee way happier. Why apply to such elite schools? Why the Ivy Leagues? Why Boston?

I think I was just caught up in this idea of status. That it was a sign—like, if I go to Harvard, I’ll be a better person than if I don’t go to Harvard. But boy, it’s been funny, you know, my son, Will, is 17, and he’s applying to colleges this year.

(laughs) My wife and I have been emphatic that he’s not applying to the Ivy Leagues.

Of course, there are a lot of factors why I wasn’t happy, and I probably explain them better in the book. But it was certainly crazy thinking that I wanted to go to an East Coast boarding school, and an elite East Coast college. I still look back, and…

… (laughs) God, it was just goofy thinking.

Sandy and Hunter separated when you were a young teenager, before you left for boarding school. The divorce took a while to formalize, but after Sandy moved out, she started dating a cast of younger men, just like Hunter started dating a cast of younger women. This similarity, their attraction to people much younger than them, made me wonder if it revealed something shared in their personalities. Were they both particularly seduced by youth?

That’s funny, I’ve never actually seen that parallel.

Yes, though. Both of them valued youth and attractiveness. And what’s funny about my dad is that the older he got, the younger the women got. He was in his early 60s, and he was dating women in their early 20s. They were younger than me—that was really strange.

You got older, and the girlfriends got younger.

(laughs) Yeah, exactly.

Deborah Fuller was essentially Hunter’s long-term partner, but they were never sexually intimate. How was Deb able to stay—and deal—with Hunter for so long? It’s not entirely rare, I suppose. There’s Howard Austen and Gore Vidal, after all. Did Hunter need Deb? Would he have been able to continue to write without her? Was she his muse?

The most important thing to know about Deb is that she just loved Hunter. Her motivation was to take care of Hunter because she loved him. It wasn’t a romantic relationship. It was a deep friendship. He trusted her because he knew she had no ulterior motives. She didn’t want anything from him. She deeply cared for him, and she made sure he was all right, often at her own expense. Hunter didn’t pay her for most of the work she did in the 20-plus years she took care of him.

She did the basics. She paid the bills. She kept his life on track, in order—so that he actually could write. After a while, he really couldn’t take care of himself. He was just out of practice, or because of the long-term drugs and alcohol, he just couldn’t focus. There was a point, when he got older and physically worse, he couldn’t do simple stuff, like go grocery shopping.

Deb also provided Hunter with some stability. When he was depressed or particularly anxious, she was there to tell him it would all be fine.

I believe a lot of people would be interested to know that you took acid with your mother (not Hunter, and never with Hunter), when you were 14. You even go so far as to claim that Hunter would have been disappointed—you mention hearing that Hunter said at a lecture that he would “beat the shit out of” you if he knew you had taken LSD, even though he’d offer you drugs as an adult. It appears he didn’t really encourage your wild side.

Why would he have been so opposed? Did he want you to be anything like him, or did he pride himself in the fact that, in many ways, you ended up not like him at all?

Hunter was surprised and pleased that I actually grew up apparently sane—able to hold a job and sustain a relationship. I wasn’t a total basket case, thankfully. I think if I decided to emulate him, he would have been appalled.

Hunter emphasized that everyone should do their own thing. Don’t do what someone else does. So, yes, he was relieved I didn’t end up like him, but he was also probably thrilled that I didn’t feel compelled to follow in his footsteps.

And even with the writing, I was reluctant for a long time to even think about writing—to be compared to Hunter. So my writing style is completely different from Hunter’s, and I think if he were able to read the book, he’d be happy that’s the case. Just like those people who try to imitate Hunter’s writing, don’t do that… (laughs) it’s never good.

One last thing: Why did Sandy and Hunter name you Juan?

Hunter was a foreign correspondent in South America for a couple of years during the early ‘60s, and then when it came time to pick a name—you know, it’s funny, his mother was very traditional, and pretty much everybody in the Thompson family has a name that comes off the family tree in some way. Hunter had no interest in following that tradition (laughs). He didn’t care about that at all. He chose a name that he liked.

He picked Juan. My middle name, Fitzgerald—I think was both a tribute to the writer and to the president.

And I can imagine with his attention to rhythm and language. He liked the sound of it. It had a good rhythm.

Juan F. Thompson does have a ring to it. The cadence isn’t too far off from Hunter S. Thompson.

It has a nice flow to it. And I do not doubt for a second he wasn’t conscious of that.

When he would read, or when he would have people read stuff he had written back to him, he was very—he would like count the beats.

And if someone couldn’t read it with the proper cadence, it was over.

Shares