“Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

— Oliver Wendell Holmes, “Buck v. Bell”

“I don’t want to be a criminal. I want to be normal.”

— Steven Avery, “Making a Murderer”

Everyone in the world, it seems, is watching “Making a Murderer,” the Netflix original documentary series about crime, punishment, guilt and innocence. The 10-hour series, which follows the legal drama of Steven Avery, a Wisconsin man jailed 18 years for a rape he didn’t commit only to face new charges in a local murder soon after his release, has grabbed viewers with shocking twists and turns, infuriating examples of shoddy police work, and the emotionally wrenching question at its heart: Was an innocent man railroaded twice?

Twitter is abuzz. Hollywood has opinions about the case (People magazine quoted tweets from Rainn Wilson, Ricky Gervais and Emmy Rossum, among others). Former prosecutor Ken Kratz has been all over the media lately lambasting the filmmakers, claiming they left out important evidence (the bits he mentioned don’t feel particularly crucial, or even verifiable, and of course his own credibility has been damaged, no matter how you feel about his work on the Avery case, by the allegations he sexually harassed a crime victim in another case, which led to his 2010 resignation).

Naturally, there have been think pieces (including Erik Nelson’s sharp cultural analysis on Salon this week). Following the phenomenal success of the podcast “Serial,” it’s pretty clear that “Making a Murderer” comes at a time when we are newly attracted to true crime narratives. More than just a popular entertainment option, “Making a Murderer,” created by filmmakers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, is a bona fide cultural event.

It’s also one of the whitest things to appear on television lately. Whiter than a Woody Allen movie. Whiter than all the episodes of “Friends” that didn’t costar Aisha Tylor. Whiter than the snow that flurries around Avery, his family and the lawyers in all those scenes set in a brutal Wisconsin winter.

So what does “Making a Murderer” have to do with race? A lot, it turns out.

As historian Nell Irvin Painter wrote in her 2010 book, “A History of White People,” while much of our nation’s historical interest in race has centered on black and white, there has always been a debate about the terms of whiteness itself. “Rather than a single, enduring definition of whiteness,” Painter writes, “we find multiple enlargements occurring against a backdrop of black/white dichotomy.” These “enlargements” include the gradual, often contested, inclusion of Irish, Italian and other non-Anglo Saxon Europeans into the fold of white America.

A century had passed since so-called race scientists had argued that people of different races actually belonged to distinct species. But as the late 19th century ended and the 20th century began, the categorizing of human beings was anything but fading – with the burgeoning of the eugenics movement, scientific racism moved from theory to practice. No longer satisfied with simply studying the differences among people – using calipers to measure head size and shape, assigning labels to skin color and hair texture – now the race scientists turned toward identifying families marred by “defective heredity” and preventing their ranks from reproducing through coerced or forced sterilization.

Among the social scientists who created the modern eugenics movement were Richard L. Dugdale, whose study of prisons led him to create a mythical family, the Jukes, whose members form an archetype of the “degenerate white.” As Dugdale wrote, “…fornication, either consanguineous or not, is the backborn of their habits, flanked on one side by pauperism, on the other by crime.” Undereducated, lazy, illegitimate and often afflicted with syphilis, the Jukes represented the weakest branch on the white family tree.

Henry H. Goddard, a researcher who worked at the Vineland Training School for Feeble-Minded Girls and Boys in New Jersey, invented the second great mythical family of eugenics, the Kallikaks, based on a young woman he had studied at Vineland. Although Goddard noted that she was attractive enough to get a man and have babies, the pseudonymous Deborah Kallikak had the mind of a child, and was certain to spawn another generation of mental and moral defectives. His book, “The Kallikak Family,” published in 1912 (“to a fine critical reception,” Painter archly points out), argued that something had to be done to prevent their further spread. “There are Kallikak families all about us,” Goddard wrote; “they are multiplying at twice the rate of the general population.” As Painter notes, many successful whites saw such flawed heredity as “a threat to the welfare of the race.” How can white supremacy stand when some whites are so clearly inferior?

Against this history, it’s impossible not to see the Avery family at the center of “Making a Murderer” as a contemporary version of the Kallikaks and the Jukes.

In the first episode, Reesa Evans, the public defender assigned to Steven Avery in the 1985 rape case that first sent him to prison, lays out the social structure of Manitowoc County, Wisconsin. “Manitowoc County is working class farmers. And the Avery family, they weren’t that,” she says, noting that the Avery business was an auto junkyard, not a farm. “They dealt in junk. … They didn’t dress like everybody else. They didn’t have education like other people. They weren’t involved in all the community activities. I don’t think it ever crossed their mind that they should try to fit into the community. They fit into the community that they had built.”

Avery’s cousin Kim Ducat argued that the police prejudged Avery based on his family. “There goes another Avery. They’re all trouble,” was how she characterized the local attitude.

Evans agreed. “Sheriff’s department saw [Avery family] as kind of a problem, and definitely undesirable members of the community.” As for Steve, she describes looking at his educational records and seeing that he “barely functioned in school. His IQ was 70.”

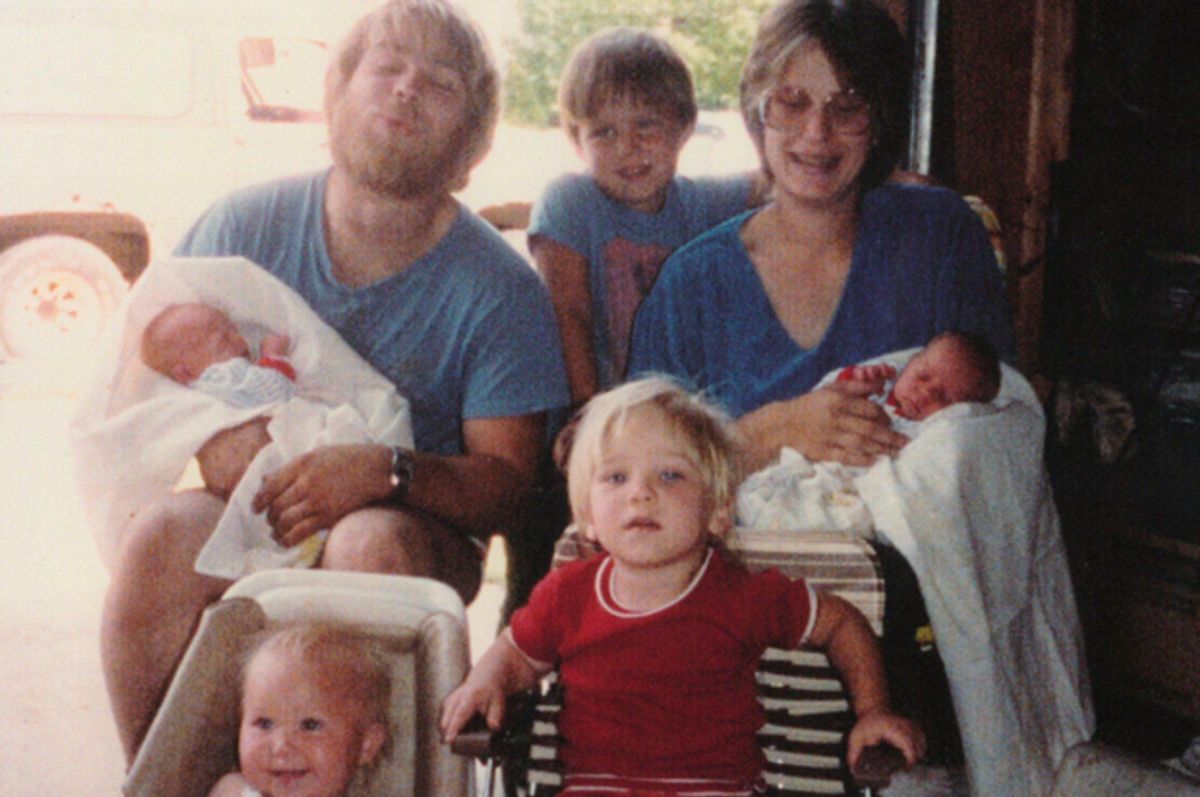

After Avery was sent away for the 1985 rape conviction, we learn, he was separated from the five children he loved. We see their pictures. They’re pale, with white-blond hair, skinny. One daughter has noticeably asymmetrical eyes (the kind of minor physical disfigurement that figures prominently in early eugenics tracts about hereditary fitness).

In later episodes we meet Brendan Dassey, Avery’s nephew, who becomes a key figure in his story. Rough-featured, with a hang-dog expression, Brendan has learning difficulties (a generation younger than Steve, his IQ isn’t part of the record we hear about him). One lawyer calls him “slow.” Another describes him as “intellectually limited.” Another argues, in his defense, “don’t convict him because he couldn’t pick his parents.”

“I am learning the Avery family history and about each member of the Avery family,” wrote investigator Michael O’Kelly in an email to his employer Len Kachinsky, who served as Brendan Dassey’s first defense attorney (Kachinsky was subsequently decertified by the state public defender’s office from taking homicide cases following news of his actions in the Dassey case).

“These are criminals,” the email continued. “There are members engaged in sexual activity with nieces, nephews, cousins, in-laws. … These people are pure evil. A friend of mine suggested, ‘This is a one-branch family tree. Cut this tree down. We need to end the gene pool here.’”

That's a familiar call for any student of history. Sterilization was the eugenicist’s tool of choice a century ago, when Oliver Wendell Holmes famously wrote, in a sterilization lawsuit brought by Carrie Buck before the United States Supreme Court, “three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

All of this helps explain how and why the forces of respectability in Wisconsin – the police officers, private investigators, prosecutors – lined up against the Avery family with such ease, such speed. In their eyes the Avery family wasn’t respectable. They were Jukes, Kallikaks, poor whites, hereditary losers. In this very white corner of the state, with no people of color to treat as second-class citizens, the "degenerate whites" would do just as well. I'm not saying prejudice against poor whites is anywhere near as virulent or damaging as racism against people of color. But it came from the same bad science, crackpot scientists, and inane theories. And it lingers — sometimes invisibly, sometimes making itself clear as it did in Manitowoc County.

Shares