The Dead Zone

2007

At the busy border crossing into Syria, the sun beat down onto the stream of cars that twisted out of view. A thousand reflections scissored off the windshields, mirrors, and hubcaps on vehicles that packed the road like an old junkyard. Momentarily blinded, I averted my eyes and turned toward the forbidding checkpoint out of Reyhanlï, Turkey. I was nervous, jumpy at every horn blare. Only fifteen minutes had passed since Jemal had dropped me off to park the van, but it seemed he’d been gone too long. In another fifty yards, I’d face the uniformed guards, and I had to get my story straight. I glanced at my security blanket, my gray cell phone; approximately ten in the morning, and no missed calls. In the swell of heat and exhaust on this August Friday, I felt like collapsing. On the asphalt, massive cargo trucks leaving Turkey idled. They roared on, advanced a few feet, then went off again, while pedestrians zigzagged through without fear.

I was keeping an eye out for Jemal, but my gaze kept returning to the surrounding mountains, parched and imposing, the color of dirt and not much else. The place couldn’t be more different than where we had been the afternoon before: relaxing high above the clouds in Turkey’s last Armenian village, Vakïflï Köyü, a serene oasis of stone homes and tall trees that perfectly followed the sweet serenade of the Kilis bathhouse. I’d been healthy there, too, but had fallen sick later that night. Now dehydrated and dizzy from repeatedly throwing up, I took another swig from my plastic water bottle. Water. It was all my body wanted; I could never wash enough down my sore throat. I studied the rises from ground to peak. Could I hike across these heights as my grandfather did? In this condition? Somewhere beyond this point, he had suffered the most.

I can turn around now, I told myself. But I could not. I had spent too long getting there, a day of flying to Istanbul, two weeks of traveling overland through Turkey, six months of planning, and a lifetime of family stories, all leading me to this corridor once part of the Ottoman Empire. Ever since I could remember, I had heard the dramatic tales from my mother: how my grandfather wandered for years in the desert of what is now Syria; how he, Stepan Miskjian, staggered a week with two cups of water, trying to escape from the Turks who were trying to kill him, for the crime of being Armenian.

Only halfway into my nine-hundred-mile journey, and I was already weary. And I was a well-fed thirty-six-year-old traveling by car and train, not on foot as Stepan did. I was the one sleeping in beds rated by stars, not outside on the hard ground under the constellations. Just an hour after leaving my air-conditioned hotel room, I was weak and feverish and needed a bathroom. And I was still far from my endpoint, a godforsaken mound of dirt named Marqada just short of the Iraqi border, where my grandfather’s caravan of thousands met its end.

I glanced at my cell phone again; only five minutes had elapsed. I wasn’t even moving, but rivulets of sweat were nose-diving off my forehead. Not only did I look ridiculous in my mock neo-colonial disguise of a hat, sunglasses, and baggy linens, but now, I feared, I appeared suspicious too, as if I were hiding contraband. Where is Jemal? Passport control would ask why I’d come to the region, and I wanted him there in case anything went wrong. I hadn’t been completely up-front about my research when I’d applied for a tourist visa to both countries. Ten days earlier, the Turkish police had followed and photographed me and I was still spooked. I wondered if there was some sort of file on me.

At last I heard Jemal’s cheerful voice: “Hello, Dawn!” He was carrying my luggage. With the crowds, he had had to park a distance away. After a week of his guiding me over the mountain ranges my grandfather had been forced to climb, I now had to say goodbye. I would miss his jovial laugh and his protective paternal instinct. In a few minutes, I would cross the border, the portal to the Euphrates camps, Deir Zor, the Khabur River, everything I’d read about.

Escorting me to the guard’s booth, Jemal asked for my passport. I extracted it from my money belt, always embarrassing, as I wondered what others must think of us Americans, holding our valuables so close to our underwear. He handed over my blue identification card, and the two began to talk. I smiled to deflect my nervousness. I should have been watching them, rehearsing my lines one last time, but my attention retreated to the mountains. Could I climb them? No, I couldn’t. Certainly not today. How did he do it? How did anyone?

As the officer questioned me, I tried to answer like any tourist would, expounding on my lifelong desire to visit the ancient riches of Turkey and Syria, which was partly true. I wasn’t lying per se, and I wanted to be more forthcoming, but given that it was illegal to say the words Armenian genocide in Turkey, I didn’t want to take any chances. The Turkish guard waved me through.

“Teshekkür ederim.” I thanked Jemal with my few words of Turkish.

“Rica ederim.” He smiled broadly.

As I shouldered my luggage and began to walk away, my legs felt unsteady beneath me. One more hurdle to go, with the Syrian guards. I was so close now, and I thought about the kind Arab sheikh who had sheltered my grandfather, saving his life, and whose family I was traveling to Syria to find. Not even my mother, Anahid, knew about this part of my quest. At seventy-nine, she was already beside herself with worry about me, her only daughter, and this part of the trip made her the most anxious.

In many ways, Syria was a police state, intolerant of dissent and willing to imprison those who threatened the regime. The country was ruled with a firm hand by President Bashar al-Assad. I’d heard about his infamous Mukhabarat, commonly called the Syrian secret police, which tracked its citizens and routinely accused foreigners of being spies. Still, I hadn’t been that concerned until a family friend from the region warned me about traveling there alone. “You don’t know Syria,” she’d said. “It’s not like other countries.” The United States warned travelers against going to Syria and accused Syria of sponsoring terrorism. Just the year before, armed men had attacked the American embassy in Damascus with grenades and explosives, killing one person and injuring thirteen.

“Dawn! Dawn!” I heard Jemal call out. “You . . . cannot . . . walk . . . border,” he cried in his limited English.

“Yes, I can.”

“No, it’s too far,” he said.

“How far?”

“Too far walk.”

“How far?”

“Maybe five kilometers?”

“Oh.” I glanced at the road that soon disappeared, exposed to the glare of the sun, without any visible shade. Before coming, I had imagined a short footbridge, like the one from California into Tijuana, Mexico. Instead, there was a vast no man’s land I’d have to cross. I was so stupid. After a few paces, I was melting.

“Can you take me?”

“I’m sorry, Dawn, no have papers,” he said.

Within moments, Jemal went to work on a new plan. “Wait here.” Striding into the middle of the road, where the bottleneck lifted, he began waving to passing vehicles. What is he doing? He’s going to get run over. Several drivers slowed, exchanged words with him, and then accelerated. Finally, the door of a station wagon swung open, and a middleaged guy popped out. He and Jemal approached me.

“You give five dollars,” Jemal said. “He take you.”

The man studied me, waiting for my reaction. He wasn’t much older than me, short, with dark hair. Shifting his feet, he seemed to be in a hurry. Without another choice, I reluctantly dug into my bag, and withdrew five U.S. dollars, crumpled among my Turkish liras.

Now the man gestured me to the back passenger seat. Ducking in, I realized it was overloaded with men. Not a single woman. Two sat in the front seat, three in the space next to me, and a pile of others in the trunk area with the baggage, knees pressed to chests.

“Hello,” I said. Nothing. I tried a few words in Turkish. They still didn’t respond, continuing their chatter. They spoke Arabic, I realized, stupidly slow through my fog of illness. Thumbing through my phrasebook, I attempted the basic greeting: Marhaba, shlonik? Hello, how are you? I mangled it so much their eyebrows furrowed. Inside was stuffy, the vinyl seat sticky with sweat. I knew nothing about them; they might have had contraband in the back.

As the car accelerated, I stared out the window, getting a closer look at these desecrated mountains that formed the barrier between Turkey and Syria. I had imagined the landscape of this area would be desert, similar to Palm Springs. But somehow it seemed more forsaken. It was near this border that my grandfather had first realized his life was in danger, that a much darker objective was driving the deportations.

The station wagon sped forward until a Turkish guard blocked the road. Another checkpoint. Apparently, we were still in Turkish domain. The guard scrutinized me for a little while, then spoke to the driver. He handed over his paperwork. The official flipped through the pages, then pointed to the side of the road. We were being pulled over. I panicked. Had the guards at the border crossing figured something out about me? A queasy feeling welled up in my throat. I heaved. I was about to vomit again.

The car turned to the right, parking opposite a small office. I took out my cell phone to tell my fixer on the Syrian side what was happening. God. I tried to dial. Nothing. Goddamn it. I tried again. I glanced down — there was no signal, and I was on my own.

* * *

Welcome to Syria

2007

On this barren stretch between Turkey and Syria, I felt a kick of stomach pain. I doubled over, dropping my head between my knees; the nausea intensified. Then came another wave. Still stuck in international limbo, I felt like screaming. I never foresaw that this trip across the border into Syria could go so wrong, that I would end up hitching a ride with a carload of strange men, that I would be pulled over, effectively imprisoned between the two countries and brown mountains.

The heat was stifling here, the sun’s lashings excoriating. My skin was reddening into blotches, hypersensitive because of an antibiotic I’d taken the previous night. Nearby stood the car’s other passengers. Shifting their feet, they, too, seemed impatient; our driver had been in that nearby building for what felt like ages. Are they detaining him? What has he done? How I longed to be singing my way across eastern Anatolia again with Jemal and Baykar. I was half delirious, half paranoid, certain only that I had to extract myself from this situation. On wobbly legs, I crossed the hot asphalt and strode through the ripples of heat to the Turkish sentry stationed outside the office.

“Do you speak English?”

“A little,” he said.

“I’m not with these men. I just met them. Can I continue on by foot?”

“It is still very far,” he said.

Defeated, I sat back down in the blistering sun. A lone branch of shade barely covered an arm, and I contorted in vain into its silhouette. Finally, our driver came barreling out the door, rushing toward us. He motioned for us to get back into the car. After we’d piled in again, the station wagon sped the remaining distance, the road winding at a slight grade. I couldn’t believe that I’d thought I could walk this in my depleted state. Up ahead loomed the Syrian checkpoint, spanning the road like a bridge. The last hurdle, I thought.

In that moment, another officer stepped into our lane and waved us down. Beside the car, he addressed the men in Arabic. At once, my fellow passengers retrieved their passports and gave them to the officer, signaling for me to do the same; at least, that’s what I assumed their gestures meant. Leaning forward, I handed mine to the official. After a brief inspection, he began to return the precious documents, fanning them out around the car like sold-out concert tickets. Nearly incoherent from my sickness, I extended my hand, expectant. Instead, he directed me out of the car with a stern voice. Now I really started to panic.

Through the windows, the car’s men stared at me as I extracted my heavy roller bag from the trunk. They were all strangers to me, but they were more comforting than this guard, who now led me to a spartan governmental office. There, an official sat behind a desk busily questioning another foreigner, a young girl in her twenties. When finished, he turned to me, his demeanor pleasant as I took the hot seat. I tried to appear calm.

“Why have you come to Syria?”

“I want to visit the country.”

I kept quiet about retracing the deportation route. An Armenian filmmaker had shared with me his experience of being granted permission to shoot a documentary about the genocide and then having it revoked. I couldn’t jeopardize this trip; I needed to find the family of the Arab sheikh who’d saved my grandfather. I didn’t even know if this was possible, but I had to try. So I had decided to enter as a regular tourist instead of a journalist. In essence, that was what I was. I just had different landmarks on my itinerary than most sightseers.

“Why Syria?” the man asked.

“I am also visiting someone.” Before I left, a family friend had insisted I stay with her aunt, a resident of Aleppo, so I wouldn’t be completely on my own. I argued with her for the longest time, maintaining that I had plenty of experience traveling in foreign countries and handling unexpected situations. “It will be easier if I just check in to a hotel,” I said, not wanting to impose, but she wouldn’t hear of it. As I sat in this office now, trapped, I felt immensely grateful for her persistence. Someone is expecting me, I told myself, someone will know if I go missing. The official flipped through the pages in my passport and lingered on one, covered in stamps. “Why did you visit Brazil?”

“For vacation,” I said. I found this questioning so curious: How could my trip to the Amazon, where I fished for piranhas, now be suspicious? I was no fearless femme fatale agent, though I could understand the mistaken identity. In Brazil, I ran at the speed of light from a tiny spider and courageously posed next to a restrained baby crocodile. The inspector’s mistrust was astonishing, yet real, and he pressed me on the specifics for the next hour, almost down to the number of bugs that had stung each leg. I was trying to appear casual, but my arm began to shake, so I braced it in between my knees. Finally, a middle-aged man with cropped hair appeared at the doorway and spoke in Arabic. I recognized his strong voice and lilting cadence. It was my Syrian translator, Levon (whose name I’ve changed). I’d never met him in person, but I had spoken to him several times before my arrival and, thanks to the urging from my family friend, had requested he meet me on the Syrian side.

“Parev,” we said to each other in Armenian. “One minute,” he said, and he vouched for me to the official. Into his hands, I was soon released, and we drove the remaining miles to Aleppo, passing arid land dotted with square homes. I’d learn later that this suspicious treatment at the border was standard fare for foreigners entering the country. But what had begun as routine escalated into something else the farther I traveled into the country. In the car, Levon quickly shifted gears from rescuer to tour guide and began to tell me about their thriving community of a hundred thousand, the majority living in Aleppo. Many Syrian-Armenians were originally from Anatolia, Levon explained, and had settled there following the Armenian genocide.

After we wound through the sprawl of the city, Levon dropped me off at my contact’s spacious house, where I crashed for days, vomiting, curled up like a worm. Her poof of a white poodle kept tiptoeing into my room, curious about the visitor, her nails against the tile always foretelling her arrival. I had a permit to remain in the country for only two short weeks, and precious days were passing as I slept, febrile, the air oppressively hot. I couldn’t imagine lying outside in this state, exposed to the sun or snowdrifts, like my grandfather. Despite a soft bed and a gracious host as nurse, I was miserable. At last, that Monday, my powerful antibiotic finally chased down my temperature. Not losing another minute, I climbed into the back seat of a taxi, an Armenian driver behind the steering wheel and Levon in the passenger seat. Together, we set out east to visit the region that was once riddled with camps, the places where my grandfather had lived and nearly died.

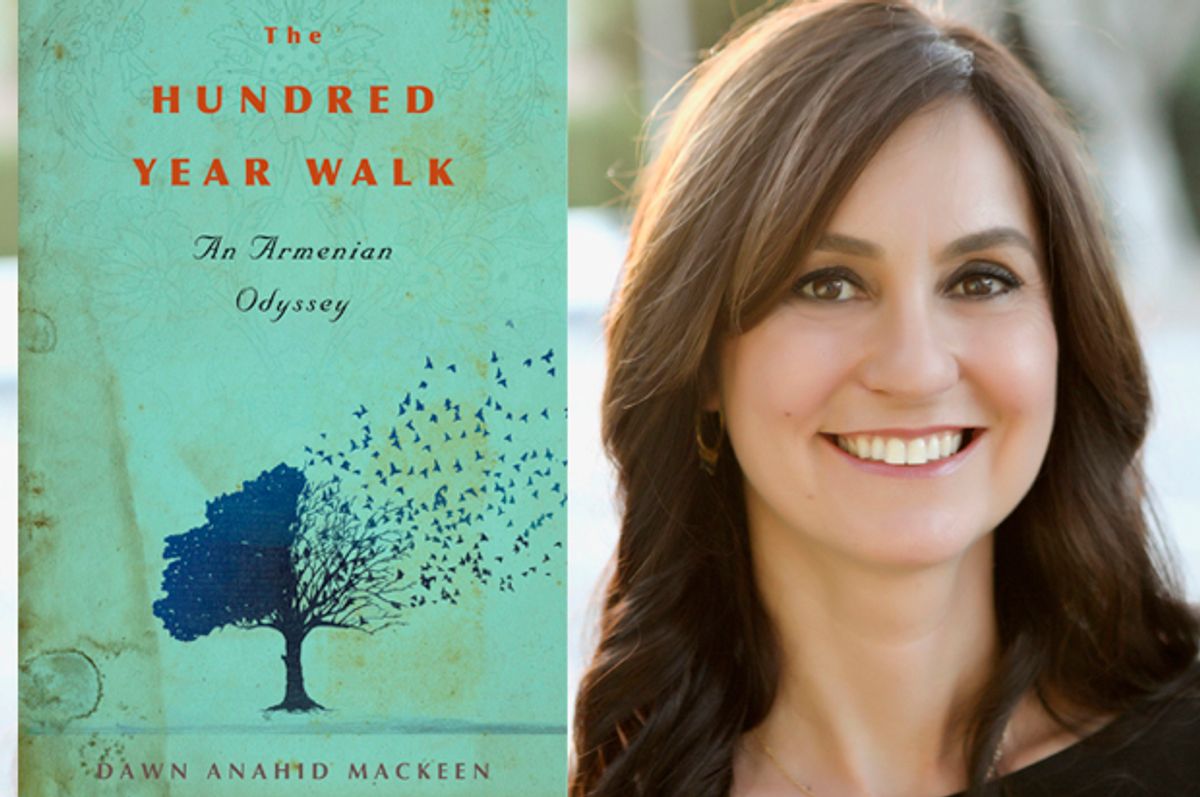

Excerpted from "THE HUNDRED-YEAR WALK: An Armenian Odyssey" by Dawn Anahid MacKeen. Copyright © 2016 by Dawn Anahid MacKeen. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Shares