On Jan. 30, the Polynesian Football Hall of Fame honored five men as its third class of inductees. Troy Polamalu, the recently retired Pittsburgh Steeler with the incandescent smile and wild hair, will attract the most attention. He’s the only inductee well known outside of small circles of fans. But each of these men—Alopati "Al" Lolotai, Charley Ane, Rocky Freitas, Vai Sikahema and Polamalu—embodies the intimate, if painful, connection between football and Polynesian culture.

Football has reached a crossroads, its future imperiled by the very physicality driving its popularity. The number of boys playing Pop Warner and high school ball plunged over the last decade as the neurological, physical and fiscal costs of the game became more troubling. That’s on top of the already severe decline in the game’s scholastic ranks in the Rust Belt—football’s original heartland—during the 1980s and ‘90s.

But one group has bucked that trend—Polynesians, especially Samoans in American Samoa, Hawaii, California and Utah, as well as in pockets of Texas and the Pacific Northwest. American Samoa is the only place outside the United States where football has taken hold at the grass roots, the only one that sends its native sons to the NFL. In just a few decades, the sons of Samoa and Tonga, mostly young men who came of age in the States, have quietly become the most disproportionately over-represented demographic in college and professional football.

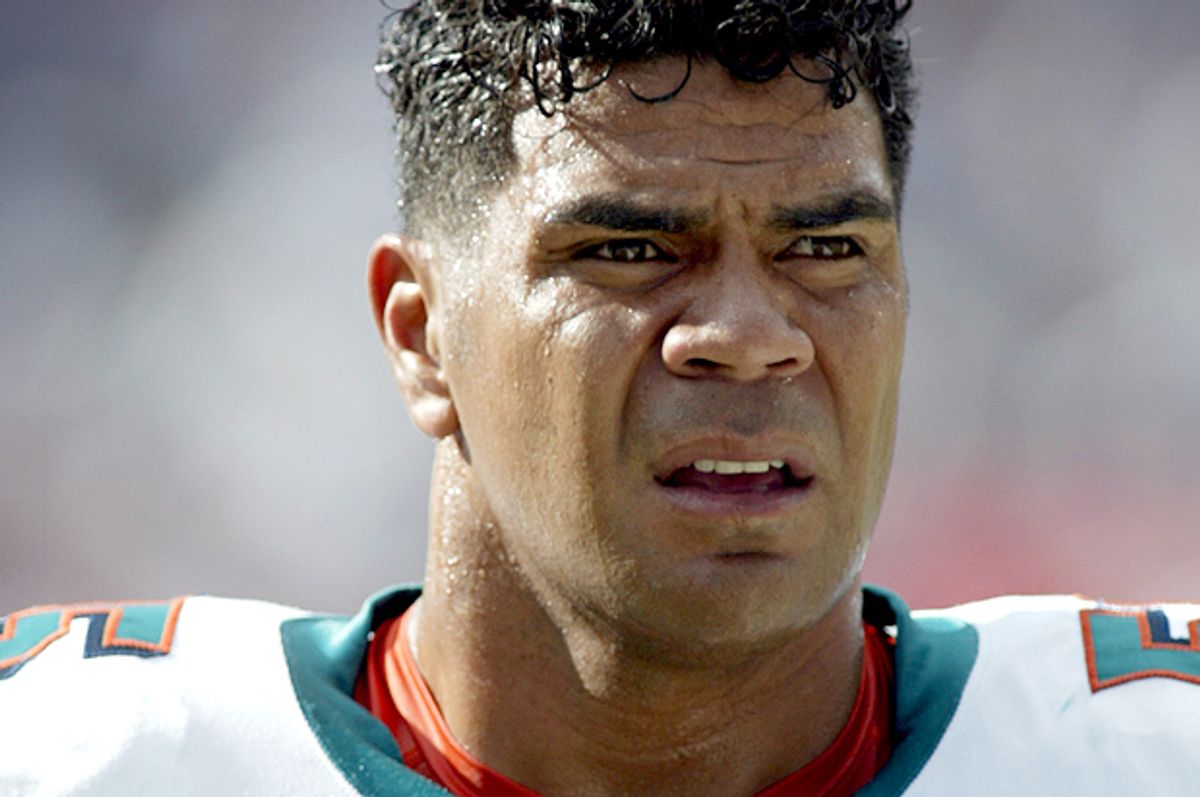

Football has become the story Samoans tell about themselves to the world. But the narrative has grown bittersweet. While creating a stunning micro-culture of sporting excellence, these athletic outliers are paying a steep price for their commitment to the game. Sadly, that which makes them so good at football—their extraordinary internalization of discipline and warrior self-image that drives them to play with no fefe (no fear)—also makes them especially vulnerable. Nobody lived and died that irony more than Junior Seau, who became the first Samoan in the Pro Football Hall of Fame after a 20-season NFL career in which, inexplicably, he was never diagnosed with a concussion. Not long after retiring, Seau shot himself in the chest, unable to live with the demons of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the tragic downside of playing with no fefe.

The five inductees have seen more clearly than most what football gives to those who play it and what it takes from them. They span the 80 seasons since Al Lolotai became the first Samoan to enter the NFL in the wake of World War II. Charley Ane, the second Samoan in the NFL, surpassed Lolotai on the field, earning two championship rings with the Detroit Lions. Rockne "Rocky" Freitas, a native Hawaiian who starred at every level of the game before returning home, became an educator, most recently as the chancellor of the West Oahu campus of the University of Hawaii. Vai Sikahema, born in Nukuʻalofa, Tonga, became the kingdom’s first NFL player. He played for Brigham Young University’s 1984 championship team and forged a Pro Bowl career before becoming a journalist in Philadelphia and a leader in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Troy Polamalu, the 2010 NFL defensive player of the year and two-time Super Bowl champion, will almost certainly join Junior Seau in the Pro Football Hall of Fame as soon as he is eligible. Over the last four years, Polamalu and his wife, Theodora, have taken hundreds of coaches, educators and medical personnel to American Samoa, where their Faʻa Samoa Initiative works with youth to build social capital by imparting life skills to help in the classroom and workplace as much as on the ball field.

Paladins of a culture of sport in which community meant more than money, these men mattered as much after they stopped playing as during their athletic prime. While each excelled on the field, what sets them apart from most athletes was their life-long sense of tautua, what Samoans call service. Each gave back as much as he got from the highly competitive culture that provided the drive to succeed. That commitment brought Al Lolotai back to American Samoa in the late 1960s, and will bring Polamalu there for years to come.

Born in what was then German Western Samoa, Al Lolotai moved to American Samoa and then to Laʻie on the north shore of Oahu, where the Mormons built a temple early last century as a gathering spot for converts from the South Pacific. Lolotai joined the Washington Redskins after World War II. Though owner George Preston Marshall long resisted playing African-Americans, the dark-skinned Lolotai apparently did not affront his or Washington fans’ racial sensibilities. Lolotai gained greater notoriety as a wrestler after leaving football. Performing as Sweet Leilani, he won multiple championships, the last when he was 58. His nephew Dwayne "the Rock" Johnson would also play football and wrestle before becoming one of Hollywood’s more bankable actors. Lolotai’s most enduring legacy came when he returned to direct health education and sport in American Samoa’s schools in the late 1960s. “He started our sports programs out of nothing,” Tufele Liʻamatua, the director of Samoan affairs, told me in 2011, shortly before his death. “He helped bring football to our island.”

Honolulu-born Charley Ane, whose father was recruited to Hawaii to play industrial league baseball, became the first Samoan at the Punahou School. There, at USC, and with the Detroit Lions, Ane was the archetypal Samoan, the quintessential teammate who brought the locker room together. In Detroit, Ane’s blocking gave quarterback Bobby Layne time to do what he did best—improvise like a jazz musician. Detroit made it to the NFL championship game three times in Ane’s first five years and won twice. Teammates voted him their captain for the 1958 and 1959 seasons. And when his playing days were over, Ane gave back as a coach at five high schools. Freitas and Sikahema came later, but like Lolotai and Ane, remained rooted in community and service.

Junior Seau’s selection to the Pro Football Hall of Fame last summer and Marcus Mariotta’s Heisman Trophy honors a few months before—both firsts for Samoans—herald a growing wave of Polynesian talent. They are the descendants of a people who resisted conquest and colonization, but embraced Christianity in the 1800s and the U.S. military during World War II. The confluence of religion, military discipline and Faʻa Samoa (in the way of Samoa) created a football culture that coaches cherish.

Robert Louis Stevenson, who spent the last years of his life in Western Samoa, once called Samoans "god's best, at least, god's sweetest works." The more I know about these men and their back stories, the more I realize why Stevenson fell in love with Polynesians and their culture.

But there's a cost to this devotion to football, to playing with no fefe. Samoan boys, who train year-round on fields blistered with volcanic pebbles and use helmets that should have been discarded long ago, incur far too much neurological damage. They have a difficult time adjusting to college and maximizing the benefit of an athletic scholarship. More important, this micro-culture of football excellence coexists with a public health crisis. Samoans and Tongans are among the most diabetic and obese people on the planet, the consequence of forsaking a traditional diet for cheap and fast food.

Polynesians and youth from other disadvantaged communities may be the salvation of America’s most successful sporting enterprise at a time when the sons of better-off families are deserting the game. But the five men to be inducted into the Polynesian Football Hall of Fame this month tell a much deeper and meaningful story of sport and community.

Rob Ruck is a historian of sport at the University of Pittsburgh, currently finishing a book about football and Samoans. His last book, "Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game," was a finalist for the PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing.

Shares