It's a new day for American drug policy, at least as far as drug users are concerned. In New Hampshire, Jeb Bush, Carly Fiorina and Chris Christie are speaking to the wrenching pain of losing loved ones to opioid addiction and death, and making the case that drug abuse should be treated by health professionals and not jails.

“I can look in people’s eyes and I know that they’ve gone through the same thing that Columba and I have,” said Bush, referring to his daughter's struggle with addiction.

New Hampshire, a 94 percent white state holding the first-in-the-nation primary, has been hit particularly hard. Last year, the state recorded at least 385 drug deaths, according to New Hampshire Public Radio. Nearly two-thirds of those involved the dangerously powerful opioid fentanyl, which is often mixed with heroin. The state's 73.5 percent spike in overdose deaths between 2013 and 2014 was the second largest nationwide.

Republicans on the campaign trail are opening their hearts to addicts and their families, and policymakers from both major parties are backing harm reduction measures like increasing access to the overdose-reversing drug naloxone. The shift in tone and policy is important, and it has understandably caught reporters' attention.

“In speaking about their own experiences, Republican candidates are not only allowing themselves to be vulnerable in front of voters, they’re also straying from the just-say-no message of Ronald Reagan, whose legacy includes a tough legislative stance on drugs and drug sentencing,” writes the New York Times' Emma Roller.

The seeming about-face, however, also reveals a troubling problem: Heroin user demographics have changed dramatically in recent years, from heavily black to overwhelmingly white; and it seems that for politicians, it is the opioid crisis' newly white face that has lent it a relatable quality as far as drug users are concerned. This has not so much been the case for drug dealers.

A 2014 study published in JAMA Psychiatry highlights the enormous demographic change that has taken place. Amongst surveyed users who started on heroin prior to the 1980s, whites and nonwhites were equally represented (meaning heroin users were disproportionately nonwhite). Among those who started using heroin in the last decade, however, nearly 90 percent were white, and most, unlike the older cohort, got their start on prescription opioids.

“Heroin use has changed from an inner-city, minority-centered problem to one that has a more widespread geographical distribution, involving primarily white men and women in their late 20s living outside of large urban areas,” the authors conclude.

And therein lies the rub: While many have noted the racial double standard at work, little attention has been paid to its ongoing and pernicious consequence -- policy makers are often still approaching drug dealers with ruthlessly punitive measures, and those drug dealers are likely to be black and Hispanic. At least, that is, those for drug dealers who are serving prison time: studies have found that in reality whites are more likely to sell drugs than blacks.

It turns out that Bush and company are not straying as far from drug war orthodoxy as it might seem at first blush.

“For dealers, they ought to be put away forever as far as I’m concerned,” said Bush, summarizing the new compassionate consensus's harsh edge. “But users — I think we have to be a second-chance country.”

While the face of drug users is becoming white, the image of drug dealers often remains black or Hispanic, as blunt-speaking Maine Gov. Ron LePage recently made clear.

“These are guys with the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty – these types of guys – they come from Connecticut and New York, they come up here, they sell their heroin, they go back home,” said LePage. “Incidentally, half the time they impregnate a young white girl before they leave, which is a real sad thing because then we have another issue we have to deal with down the road.”

LePage's comments prompted outrage and ridicule because they were racist. But the policy implications go beyond rhetorical offense, because the growing empathy toward white heroin users could actually reinforce or even increase hostility toward drug dealers, especially if they are perceived as being black and Hispanic. Ted Cruz, for one, blamed drug problems on borders left open for "undocumented Democrats." The upshot is that growing compassion toward drug users won't necessarily lead to a major reduction in the number of drug offenders behind bars. Drug dealers already made up the bulk of people serving time for drug crimes, and so the only way to sharply reduce the number of drug offenders in prison is to stop imprisoning so many drug dealers.

Instead, some officials appear to be heading in the opposite direction. Around the country, federal and local prosecutors are pointing to the opioid epidemic as a pretext to charge drug dealers with murder-type offenses in fatal overdoses. In reality, the sort of dealers who Bush and others want to put away for life include both small-time operators and drug users who appear to have shared a small amount of drugs with a friend. One man was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison for selling two-tenths of a gram of heroin, $30 worth, to a man who later overdosed. Many dealers, major and minor, are still subject to sentences harsher that what many countries reserve for murderers.

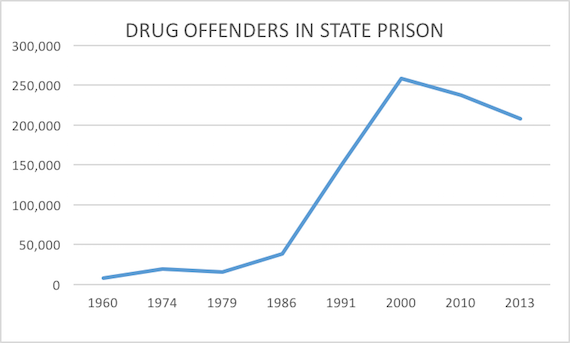

Even as politicians embrace addicts, the number of people serving time for drug crimes in prison has declined, but only rather modestly in recent years. State prisons' estimated drug offender population dropped from an estimated 258,100 in 2000 to 208,000 in 2013, while federal prisons' fell from 99,900 at the end of 2011 to roughly 96,000 as of the end of September 2014. These drops are nowhere near close to offsetting the astronomical increases in prison populations population over the past three-plus decades, thanks to the War on Drugs.

[caption id="attachment_14387806" align="alignnone" width="570"] (Estimates from some years exclude prisoners serving sentences of less than one year. Prior to 1999, estimates for offense distribution were based on periodic inmate surveys. From 1999 forward, offense distributions for state offenders were based on administrative individual-level records collected through the National Corrections Reporting Program. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics.)[/caption]

(Estimates from some years exclude prisoners serving sentences of less than one year. Prior to 1999, estimates for offense distribution were based on periodic inmate surveys. From 1999 forward, offense distributions for state offenders were based on administrative individual-level records collected through the National Corrections Reporting Program. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics.)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_14389141" align="alignnone" width="570"] (Estimates from some years exclude prisoners serving sentences of less than one year. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics.)[/caption]

(Estimates from some years exclude prisoners serving sentences of less than one year. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics.)[/caption]

It's not just a problem for Republicans, either. Democratic candidates for president Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have yet to put forward a plan that would actually end the mass incarceration of drug offenders (let alone mass incarceration more generally, which is driven in significant part by the imprisonment of violent offenders).

Both have bigger plans than Republicans, however, and Sanders has outdone Clinton by calling for an end to the federal prohibition of marijuana and supporting the reinstatement of federal parole. Both pledge to do something about harsh mandatory minimum sentences. But neither candidate has argued that most drug dealers should not be imprisoned, or suggested more radical but useful alternatives like broad-based legalization and regulation.

In any case, it would be up to the states to reduce most of the drug offender prisoner population, since they incarcerate the vast majority of prisoners (roughly 87 percent as of the end of 2014). But the president can help set the tone.

Compassion towards users will not reduce the drug war's hugely disproportionate impact on people of color. Of the nearly 22,000 people recorded as sentenced to federal prison for drug dealing convictions in fiscal year 2014, 25 percent were black and 47 percent were Hispanic, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission. Twenty-four percent were white, a figure driven in significant part by the disproportionate number of whites (38-percent) sentenced on methamphetamine charges. When it comes to heroin, 38 percent of those sentenced were black and 46-percent were Hispanic. And though the politics of the drug war are racist, and its impact racially disproportionate, it is important to emphasize that many white people are imprisoned for harsh, long sentences.

[caption id="attachment_14387809" align="alignnone" width="570"] (Estimates are based on state prisoners with a sentence of more than 1 year under the jurisdiction of state correctional officials. Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics, 2013; National Corrections Reporting Program, 2013; and Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities, 2004.)[/caption]

(Estimates are based on state prisoners with a sentence of more than 1 year under the jurisdiction of state correctional officials. Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics, 2013; National Corrections Reporting Program, 2013; and Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities, 2004.)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_14387810" align="alignnone" width="570"] (Counts are based on prisoners with a sentence of more than 1 year under federal jurisdiction. Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics Program and Federal Justice Statistics Program, 2014.)[/caption]

(Counts are based on prisoners with a sentence of more than 1 year under federal jurisdiction. Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics Program and Federal Justice Statistics Program, 2014.)[/caption]

The same is true on the state level, where as of the end of 2013 an estimated 67,800 drug prisoners were white, 79,900 were black, and 39,900 were Hispanic—a hugely disproportionate incarceration rate for black people compared to their overall population.

There is some movement to relax harsh punishments for nonviolent drug dealers and create programs to divert low-level dealers from prison. In Congress, bipartisan legislation would modestly reform some of the harshest mandatory minimums for drug dealers, President Obama has commuted the sentences of some drug offenders serving incredibly long federal sentences, and the racist discrepancy between federal crack and powder cocaine sentences have been narrowed (but not at all eliminated). But until politicians' rethinking of the drug war extends to drug dealers, hundreds of thousands of people, disproportionately people of color, will be remain bars in the name of a drug war that by all honest accounts has failed to stop people from using drugs.

Shares