My husband and I joined the Netflix revolution just a few months ago, which is how I became addicted to "The Walking Dead." My conversations with family and friends generally fix on two topics: what we’re watching or reading, and the election. My "TWD" Netflix binge does not impress, because, some of them say, they cannot take seriously a show about zombies — despite its 19 million viewers, according to Nielsen ratings, more than those who watched the Republican and Democratic debates combined. ("The Walking Dead" returns for the second half of season 6 tonight on AMC.)

“It’s not about the zombies,” I tell them. It’s about the human condition, spirituality, diplomacy, security, leadership, empathy…all important topics to consider in an election season.

Yes, empathy … even for those symbolic walkers, who did not ask for their deadly condition. Viewers are frequently reminded that they were once human, too. Rick Grimes (played by Andrew Lincoln), who emerges as the leader of a group of survivors, sets the tone for empathy in the first season when he says to a walker, “I’m sorry this happened to you,” just before he puts it down. In another episode when the group must use parts of a walker’s body to disguise themselves for escape, Rick finds a driver’s license in a wallet, and gives the group the walker’s (human) name. He asks them to pause and consider that the walker once lived as they did. Hershel, the farmer (played by Scott Wilson), even shelters and feeds them in his barn.

So, in season 3, when we see walkers being used by the Woodbury community at the behest of their corrupt governor (played by David Morrissey) for entertainment, it feels like a moral affront.

Then there is the rhetorical element, which gives us insight into characters’ motives. Rick and his group refer to the zombies as “walkers”; the governor and his henchmen call them “biters.” One label reminds us that they were once people, while the other label casts them as nothing but predators. Leaders’ words are suggestive of how they perceive their constituents. Labels matter.

Therein is a recurring theme that the group considers when they must do the unthinkable to survive: in the worst of conditions, we cannot lose our sense of humanity.

Nevertheless, the humanity theme is a hard sell to skeptics who have no truck with gore. “Zombies,” they sneer in disgust. “You might as well play a video game.”

The walkers, I remind them, are symbolic. We are faced with our own mortality every time we watch the news, just as our group faces it every episode. There are far too many headlines about ISIS, cancer, weather catastrophes, deadly viruses, humanitarian crises abroad, and more. And survivors know that worry never goes away. Rick’s group is constantly battling walkers as they endure the same problems that plagued people in their pre-pandemic lives, like domestic abuse, alcoholism, mental illness. We see what can happen when there are suddenly no facilities, no programs and no professionals to help manage them. The group must make agonizing choices as a result, choices that may even have caused some viewers to break up with the series.

For others, the show appeals to that part of us that wonders: Could I do that? Where would I go? What skills do I have to survive?

Most important, Could our leader endure the toughest of conditions, much less make a difference?

While "TWD" is set in and around Atlanta in the first four seasons, the hordes of (symbolic) walkers drive survivors to the woods, the mountains and the farms where there may be resources to live, but only if they have the weapons and the skills.

The rugged landscape is familiar to those of us who live in rural areas, like my own region of central Appalachia (just north of Atlanta), and particularly those of us only one or two generations removed from relatives who remember the Depression. We have heard stories of a time when money was worthless, and people had two choices: to live off the food they harvested or starve. We have seen industries develop and grow and now we are watching them leave. Older generations may be fatalistic when they talk about the future, but they lived through the past, and they have seen the worst.

My great-grandmother, a farmer who could outshoot a man with her own pearl-handled pistol, would not have liked "TWD," but she would have understood it from the perspective of a survivalist.

"TWD" includes a few pacifists who want nothing to do with guns, but in their world, most cannot survive without them. Nearly everyone carries some kind of weapon, even Rick’s son, Carl (played by Chandler Riggs). Herds of walkers must be controlled with guns. But guns also pose a problem because walkers are drawn by the noise. Darryl’s (played by Norman Reedus) crossbow and Michonne’s (played by Danai Gurira) sword are much better options in close combat with a few walkers, and without the worry of running out of ammunition. Noise only works in their favor if they are distracting a herd.

“But the zombies,” my beloved skeptics say, shaking their heads. “How can you stand the decay, the consumption?” Because it’s symbolic.

We see the fragility of society in the wake of a pandemic due to the lack of resources and security. We are made uncomfortable by the group’s constant suffering and fear: They are without the conveniences of running water, electricity, processed foods and cellphones. There may be transportation, but only if a car has gas and the roads are clear. With Hershel’s help, Rick and his group manage to cobble together a farm near an abandoned penitentiary in season 3. Rick’s wife has a baby on the way and now they have shelter. Hope springs eternal.

Still, the walkers -- and everything they represent -- can be counted on to take advantage of complacency and breach a comfortable life. Problems are never really gone.

Without adequate resources, some survivors regress into primitive behavior, even cannibalism. But Rick’s group retains their humanity, something they prize above all, even as their hair and beards lengthen and their clothes become tattered. They may look wild, but they learn that the cleanest, most pristine people may be the ones with the most evil of intentions.

The skeptics sigh. “We can’t get past the zombies,” they say.

Then let’s talk about leadership.

A pre-pandemic police officer, Rick develops an intuition about people that he hones to a deadly accuracy. He can be trusted with his decisions for the group’s well-being. By season 6, however, he has to make hard choices measured more by standards of survival than empathy. No one, no matter how friendly they seem, can be trusted, even as people must rely on each other. “That there,” Joe the Claimer (played by Jeff Kober), “is what you call a paradox.”

The governor (a less than tongue-in-check reference) is a man who appears to have all the qualities of leadership. The organizer of the seemingly utopian Woodbury, he has a charming personality, complete with an Elvis-coated accent. But there are early signs that he is power-hungry, if not mad. He declares a micro-war to overtake Rick’s neighboring compound, complete with a tank and a band of loyalists. His final, heinous act as Rick tries to negotiate is Hershel’s beheading, a scene reminiscent of ISIS-inspired headlines.

It may be no coincidence that season 6 is set near Washington, D. C., in the presumed “safe” zone of Alexandria. Its leader, congressperson Deanna Monroe (Tovah Feldshuh), is an idealist who promises a sustainable community. She prides herself on keeping the borders safe by excluding and exiling the dangerous people, and carefully vetting those who are invited inside. She ensures the group’s safety with a giant wall. Sound familiar?

But Rick, a seasoned veteran of the brutality on the outside, chafes under her strong-willed, untested, idealistic leadership style. “People measure you,” he advises her, “by what they can take.” Though she balks when Rick consistently warns her about the community’s weaknesses, she learns that he is right.

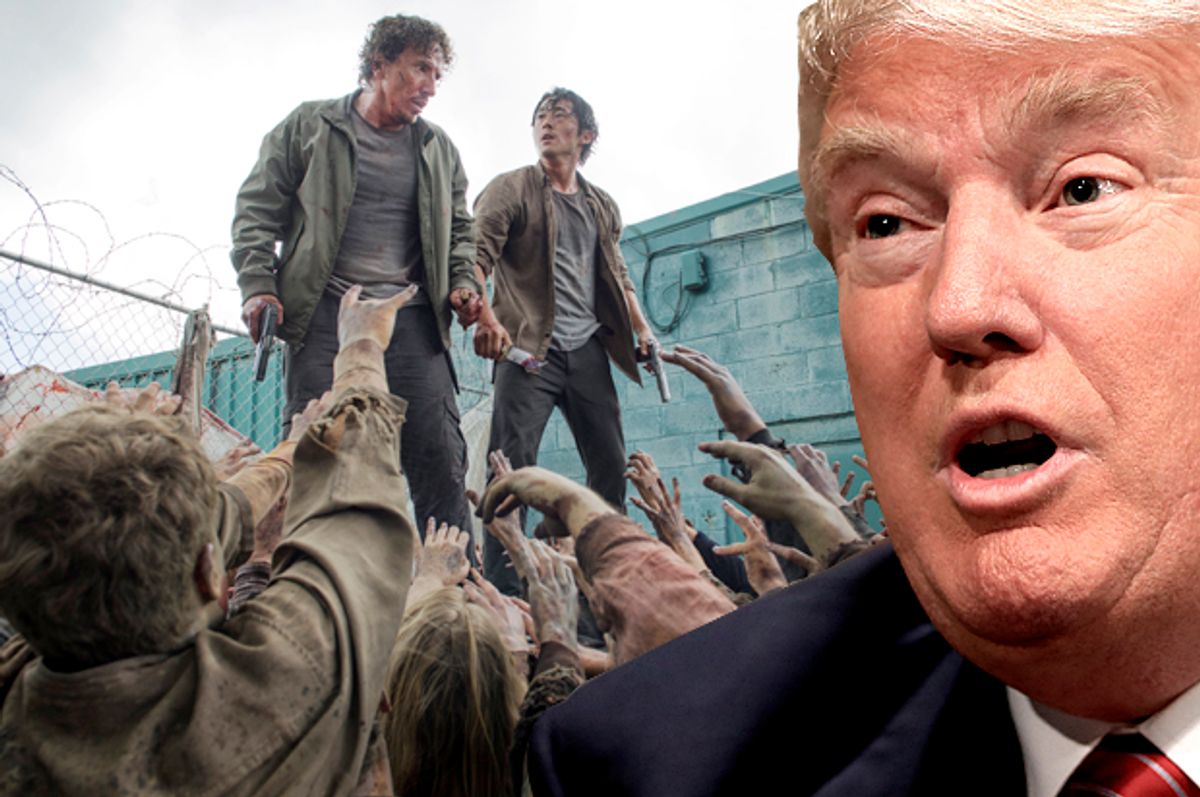

So, we need look no further than this election year, or the headlines, or the complacency of people who suddenly find themselves gobsmacked by unexpected approval ratings and caucus results to find parallels in "The Walking Dead."

We cannot drop our presidential candidates into a post-pandemic scenario to know whether they could emerge as diplomatic leaders of a safe and sustainable United States (though it may prove more reliable than debates or a caucus). It would remain to be seen whether Trump or Cruz’s Great Walls would be secure. Neither Rubio’s rehearsed zingers nor Kasich’s budgeting pride would make much of a difference. Sanders would need some hefty taxes to lead, which couldn’t happen until he resurrected an economy. Clinton would have to prove her trustworthiness, which is hard to do as threat approaches.

And no amount of noise from Trump, including bullying, intimidation and name-calling, would serve to make society safer or more sustainable. It didn’t work for the governor or Woodbury.

Maybe our candidates could take some notes from "TWD," where the quiet, observant and diplomatic Rick Grimes is still the only one standing. Diplomatic, that is, until his group is threatened, and he unleashes a small army led by Carol, Darryl and Michonne.

“How ridiculous,” my skeptics say. “We’re talking about a show with zombies.”

“Yes,” I relent, “there are zombies.” And what can we learn from them this election season?

How not to become part of a herd that is drawn to noise.

Shares