A few years ago Jim Fusilli, the pop music critic at the Wall Street Journal, was at a bar in New York with his wife, and he was finding it difficult not to eavesdrop on a conversation at the next table. A man was telling his date that no one was writing good songs anymore. The music of the ’60s and ’70s had been real and good, but today so-called artists were only interested in frivolity. His date seemed bored by the topic, but it piqued Fusilli’s interest. He’s heard countless similar arguments throughout his career, but chalks it up to what he calls a generational bias. That phrase stuck in his head, to the extent that he began referring to the unadventurous listeners who believe today’s music is only dregs as the Gee-Bees.

In early 2012, Fusilli wrote about the Gee-Bees in a column for the Journal and started a website called ReNewMusic.net, devoted to introducing out-of-touch listeners to some of the best new music being made today—from Bon Iver to D’Angelo, Frank Ocean to the Arctic Monkeys, Janelle Monae to St. Germain. And the idea led to his new book, “Catching Up: Connecting with Great 21st Century Music,” which compiles 50 of his columns with short essays on the generational bias that too often passes for deep insight or sturdy critical thinking.

“We’re surrounded by people who, despite a narrow perspective, insist the music of their youth is superior to the sounds of any other period,” he writes. “Most people who prefer old music mean no harm and it’s often a pleasure to listen to them talk about their favorite artists of the distant past. But others are bullies who intend to harangue is into submission, as if their bluster can conceal their ignorance. They ignore what seems to me something that’s self-evident: rock and pop today is as good as it’s ever been.”

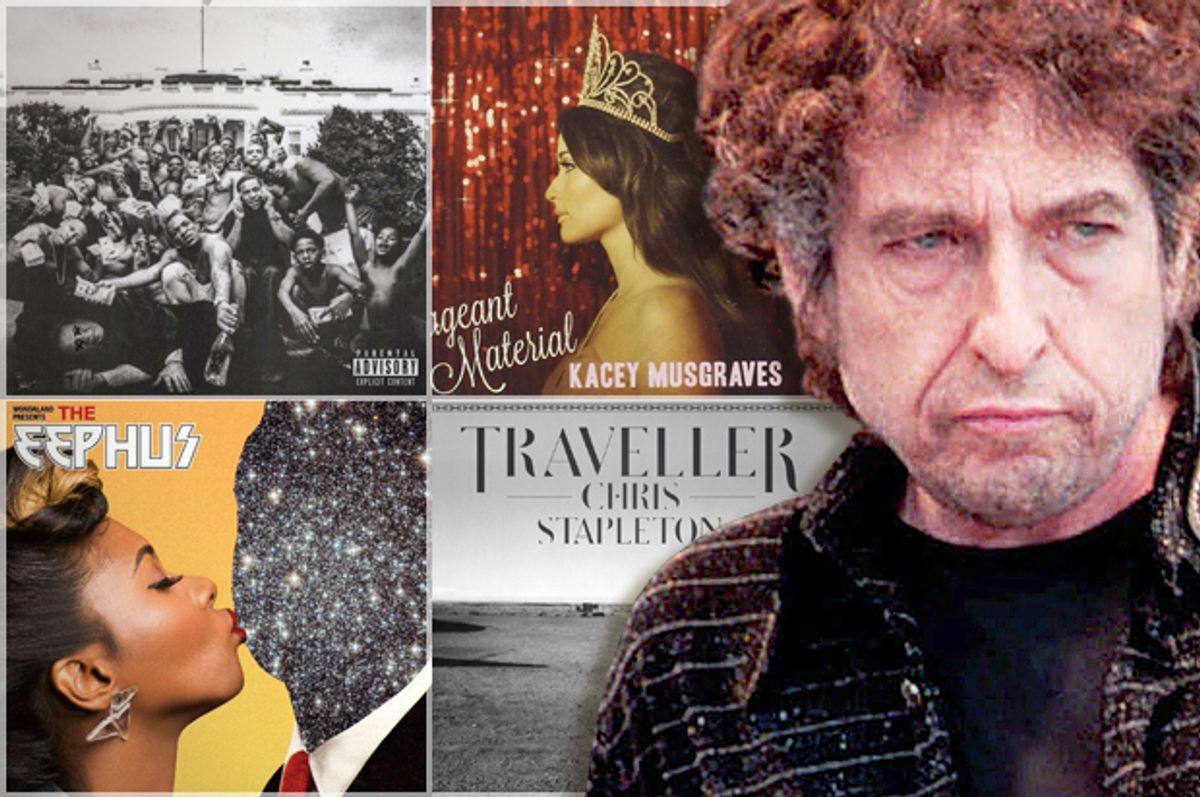

This is an important idea, especially in 2016, when pop music seems like a uniquely apt medium for a range of expression. Kendrick Lamar and Beyoncé, among others, are addressing African-American identity and police brutality in stirring songs like “Alright” and “Formation.” Adele and Taylor Swift are writing eloquently about female desire, while Sturgill Simpson and Kacey Musgraves are helping to overturn the gloss-country establishment in Nashville. And if guitar rock is your thing, look to Australia, where acts like Courtney Barnett, Royal Headache and Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever are producing some of the most exciting indie-rock anthems of the decade.

The idea that these young artists should be considered alongside the Beatles and the Stones and Dylan might be easily dismissed as another form of generational bias if it came from a millennial or even a Gen-Xer. But Fusilli is a Baby Boomer who grew up in the ’60s and ’70s and has been writing about music for most of his life. He has a deep knowledge of pop history and even penned an excellent book on the Beach Boys’ “Pet Sounds” (as part of the 33 1/3 series), but more crucially he possesses a driving curiosity about the new music. That makes “Catching Up” a galvanizing read even for those listeners who can name every jazz artist on “To Pimp a Butterfly” or every sample on Kanye’s “The Life of Pablo.” But Fusilli says he wrote the book for “people who are the opposite of the Gee-Bees—that is, secure in their status and welcoming of new ideas.”

What was the reaction when you first wrote about the Gee-Bees?

The reaction was really harsh from some people. Over the years I’ve written pieces that got some brief response, but this was really beyond anything I had seen. When you write that kind of story and you get that kind of reaction, you know you’ve struck a nerve. The idea had begun with conversations I would have at parties or in bars or any place where rock wasn’t being consumed at the moment. Some place away from music, but usually with people who knew I was a critic. Inevitably someone would say They don’t make music like they used to, and I would ask, How do you know that? If you’re listening, you know that this is really a wonderful period for music. I did a lot of thinking about it and finally wrote a piece about it for the Journal.

The responses typically fell into three camps. One was, “Yes, I know today’s music is great. I love it.” The other, “I don’t care about today’s new music because I only listen to the music of my youth.” I knew there had to be a mass of people in the middle, who would probably be open to new music if they knew more about it. My sense was that these people really would like to know what’s going on. They’re not intentionally ignoring today’s artists, but nobody talks to them about it very much—certainly not the recording industry.

How do you mean?

I don’t think the industry knows how to market music to grown-ups. When you reach a certain plateau in life and you have family and a career, when you’re involved in your community, you measure things in a different way and your affiliation with pop culture doesn’t matter as much anymore. So music ceases to be a part of your identity. It’s just music. You’re not looking for heroes at a certain stage in life. You’re just looking to hear something that excites and stimulates you. And I don’t know that the industry knows how to talk to those people. I don’t think the industry knows how to hand a grown-up a piece of music and say, This is really good for the following reasons, and none of those reasons has anything to do with clothes or hair or who they’re dating or whatever.

It’s easier to sell them another Beatles box set or a new Dylan bootleg. The industry seems to market old music to old people, so to speak.

Right. In other words, the industry keeps people in the prison that they put them in 30 years ago. You go down a dead end with some people, who say to you, Where’s the new Bob Dylan? Where’s the new Beatles? Well, there is no new Bob Dylan. There is no new Beatles. There is no new Thelonious Monk. There’s no new Duke Ellington. These people and their achievements are beyond the reach of anyone, so maybe it is interesting to empty the vaults and study how they got to be who they are. But for most artists, they had something to say in their own times, and that’s really where it belongs. My feeling is that every time somebody buys a reissue, they’re just taking money away from new musicians. They’re thwarting the growth of rock and pop. I understand the grown-ups’ instinct to do that, because it’s easier. It’s a comfortable place. You will be welcome there. But it doesn’t enrich life very much to just keep doing the same old things.

Maybe this is an unfair example. I don’t know the guy, so I’m not picking on him. But Don Henley put out that album last year, and it got a lot of buzz. Why did it get a lot of buzz? Because he used to be in the Eagles. Anybody who follows Americana and traditional country can tell you that there are 50 better albums than “Cass County.” Totally accessible work, with traditional storytelling, great vocals, great arrangements, absolutely proving that the art of songwriting is still alive. But then there’s Don Henley everywhere. Maybe this is harsh, but maybe the industry thinks it should throw a bone to grown-ups. Rather than saying this is an excellent album by a new artist, they just say, Here’s the new Don Henley.

So they’re selling a new chapter in a familiar narrative rather than a new album.

Right. A real example I can give is Chris Stapleton. I wrote about him when he was in the Steeldrivers. The second that guy opens his mouth, you know he’s for real. He writes great songs. And he’s about the nicest guy you could imagine. There are no downsides to Chris Stapleton. His album comes out last year, and it’s fantastic. But then what happens? It just sits there. A few months later, he’s on the CMAs with Justin Timberlake and suddenly everybody wants to know who Chris Stapleton is. [Note: Stapleton just performed on Monday’s Grammy Awards after winning best country album, too.] Why was there a gap? Why didn’t grown-ups hear about him when he was in the Steeldrivers? Why didn’t they hear about him when he was with his other bands? Why didn’t they hear about him when “Traveller” first came out?

What do you make of Adele, who certainly seems to have crossed over to a much wider—and older—market?

I guess the Adele album crossed over into the place where grown-ups live. But every week there are about five or six new albums coming out that would be totally in tune with the kind of music that people who grew up in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s would enjoy. Let’s be honest. Is the Adele album the best album of 2015? Is it the best album of the month it was released? The week? But it’s the one album that everybody has heard about. That isn’t to suggest that every album should get that level of exposure, but it is possible to get a message to grown-ups. Trust the fans a little more. You wouldn’t believe how many artists you know really well that people have just never heard of. And these are people who are all connected in some way to the culture at large. They can tell you what movies are coming out this Friday. They can tell you what the hot new TV shows are. They probably stream Amazon and binge-watch Netflix. But the new albums coming out… they have no idea.

It does seem like music is a medium that is marketed very differently than TV or movies or even books. Music is marketed very conservatively, as though stoking a fear of the new and the innovative.

The more you drive down on this, the more you become absolutely convinced that it’s not the consumer. People are hungry for art, and they’re not afraid of what’s new. I’m a fan of old television programs, so I’m always watching old shows on YouTube. So when I step out of that world and watch a new television show with new techniques and new modes of storytelling, I find it to be really invigorating. In the 1960s it would have taken 15 minutes to get certain information across, and today you can reveal character in new ways. You don’t hear anybody complaining about that. If people were exposed to new music, I think we could trust them to say, I don’t like that. It doesn’t work for me. Or, That’s a really interesting way to do a rock song. I’m a big believer that open-minded people can be trusted to make good decisions when it comes to music.

I wish I was as optimistic as you are, but I keep hearing variations of the same tired argument—that electronic music is somehow inauthentic, that AutoTune renders music illegitimate, that white guys playing blues-derived licks on guitars is the most honest music possible.

I don’t think it’s the critic’s job to disabuse people of their fantasies, but the truth is, if they only knew how records are made… It’s not like the Beatles woke up one morning, went into the studio, cut “Norwegian Wood,” then went to lunch. It’s never as linear as it sounds. Studio musicians came in on some of the greatest albums of the ’60s and ’70s and overdubbed parts in secret. Songs were repaired with the latest technology back then, just as songs are now repaired with the latest technology we have today. Technology has always been applied in its own time when it was necessary.

And you know as well as I do that many electronic artists are very competent musicians. They could sit down at a piano and play that tune for you. They’re not just sitting down and pressing buttons to see what happens. I remember talking to Deadmau5 a few years ago, and I said to him, I know you play piano. And he said, Yeah but don’t tell anybody. He said the idea that electronic artists are producers makes the fans feel closer to them, because there’s a sense that they could do it, too. Now that attitude has changed. Lots of electronic artists talk about their capabilities as traditional instrumentalists.

So if the idea of authenticity is keeping grown-ups from listening to new music, they’re going to be very disappointed if they ever found out how their favorite albums were made. If you listen to “Electric Ladyland,” you don’t complain that Jimi Hendrix was a master of the studio. He and Eddie Kramer were making soundscapes that still sound great today. He didn’t just walk in, plug in, and get that sound. Today, he could do all that stuff by himself in his bedroom. Can you imagine him with the kind of equipment that’s available today? Given his penchant for experimentation? Now, can you imagine him saying, I don’t want to do that because it’s not authentic?

You argue that the industry is not marketing to grown-ups. Do you feel that is part of your duty as a critic?

I do, but I also no longer believe in the gatekeeper concept. A few months ago I had a piece on Babyface. I went out to meet with him and had a very lovely meeting. I studied his history to make sure I had it. By the time the piece ran, his album had been up on Spotify for five days. I don’t think it’s reasonable anymore to think you could coerce people into following what you think, especially if it’s in conflict with their own tastes. I think our job now is to guide or accompany people toward music we think is worthy of their time and hopefully their money. We sit at the table together now, the critic and the fans.

I’m 62 years old. Back when I first started doing concert reviews, only the people [who were there] would know if what I wrote was an accurate reflection of the experience. Now, by the time people get home, the show is up on YouTube, the playlist is up, opinions have already formed. So even though I may have a platform, I’m just another voice. What I can offer as a critic is reliability and consistency, which translates into trust.

Some people claim that increased accessibility and acceleration of opinion are making the music critic redundant, but really it’s just changing the critic’s responsibilities.

Right. When I started at the “Wall Street Journal,” we were reluctant even to accept tickets to concerts. The only albums we would accept were the ones we intended to review. We didn’t want to have a relationship with the industry that went beyond what the customer might have. It sounds strange, but many times I bought a ticket to the show I reviewed. If it was at Madison Square Garden, I might be up all the way in the last row. But that was great, because that was what the fan was experiencing. My perspective was exactly the same as the fan’s, and I’ve never really forgotten that. Today, when I go to a festival, okay, I admit I might get a good parking spot. But I don’t hang out backstage. I want to have the same experience as the listener does. I just want to be part of the crowd. Because I’ve been doing it for so long, I think my body of work shows a consistent perspective on what makes music good. I hope that would make someone listen to me, but I’m just as likely to listen to them. Any critic who isn’t doing that is terribly mistaken.

There seem to be a lot of music critics whose work reads like it was written for other music critics. It creates an echo chamber effect that I think alienates a general reader who might just want to discover an album or a new approach to an old one.

I respect a lot of critics, but I never read anybody until I’ve written my column. If I pick up a newspaper or I’m on the Internet and I see somebody has written about an artist that I’m writing about, I don’t read it. I only read it after the fact. Sometimes I agree with them. Sometimes I’ll read something and wonder why it’s important. Is it really germane to the relationship between the listener and the work. It strikes me as critical showboating. We all have access, but we have access because we’re doing a story. We’re not pals with the artists. Sometimes I’ll read critics who’ll go meet an artist in their homes, and they report as if they’re just hanging out. You know as well as I do that that’s not it at all. You’re not friends with the artist, and that idea deceives the reader. It’s really troublesome, because what are you doing? You’re not aligning with the reader. You’re trying to make people think you’re a rock star. But you’re not.

One of the points of “Catching Up” that I didn’t realize needed to be made until I got several drafts into it—then I realized that it was crucial—is that if you grew up in the ’60s and ’70s, the recording industry completely dominated what you were listening to. They gave you very few tracks, if you listened to AM radio. If you listened to FM radio, they gave you a little bit more. And most of the music came from England or the U.S. Occasionally some track from a non-Anglo country would slip in, but by and large there wasn’t much diversity. When I was growing up, it was very rare to see an integrated band, and you never saw a woman in a dominant position in the band, unless they were the singer. You never saw a woman bass player, and you rarely saw a band where the woman was clearly running things. It was such a narrow world.

Exactly. You had fewer radio stations, fewer means of discovery, fewer options.

And now, of course, anything goes. If you want to listen to a radio station in Mali, no problem. If you want to listen to a band from Iceland, no problem. You can probably listen to a radio station in Mali that plays only bands from Iceland. So how’s a music fan who grew up in a very controlled environment expected to work their way through the new system? When you can listen to anything you want any time you want, it must seem like a remarkable and incredibly daunting thing. Back in the day your local AM station had a 10-song playlist, and all of those songs came from the same places. And now what do you have? Everything. And nobody has to give you permission to listen to it. There are no rules. You’ve gone from solitary confinement to the world’s largest oasis. It has to be intimidating.

Who’s going to help somebody sift through all that? Is it going to be the guy who says, I was hanging out with Kendrick Lamar, we’re riding around in his Lamborghini and blah blah blah. Or, is it going to be somebody who says, You should try this. Here’s a guy who’s putting a very penetrating and revealing narrative to free jazz. Once you step into this young man’s head, you will be changed. That’s the overarching goal I’m trying to reach both in the book and my Journal columns: to say to grown-ups, You don’t know what you’re missing. Come along. You’ll have a great time, and your life will be enriched.

Shares