As is the case with nearly every Frontline documentary, last night’s two hour “Chasing Heroin” is a riveting longform documentary feature, exploring how prescription painkillers like Oxycontin have directly led to a spike in injected heroin use. As Laura Miller wrote for Salon last spring, the number of people who have used heroin within a year has doubled from 2005 to 2012; the number of deaths due to heroin have quintupled in the past 10 years.

And most importantly, 90 percent of new heroin users are white, following what one expert calls the “heroin prep school” of prescription opiates. In America, heroin used to be linked to the “inner city,” with all the socioeconomic and racial implications that suggests. As heroin addiction has taken on a whiter, richer face, it’s become a cuddlier drug, one more likely to be responded to with help instead of force. Frontline follows different treatment approaches with a few different addicts in “Chasing Heroin,” as well as interviewing dozens of scientists, policymakers, and social workers.

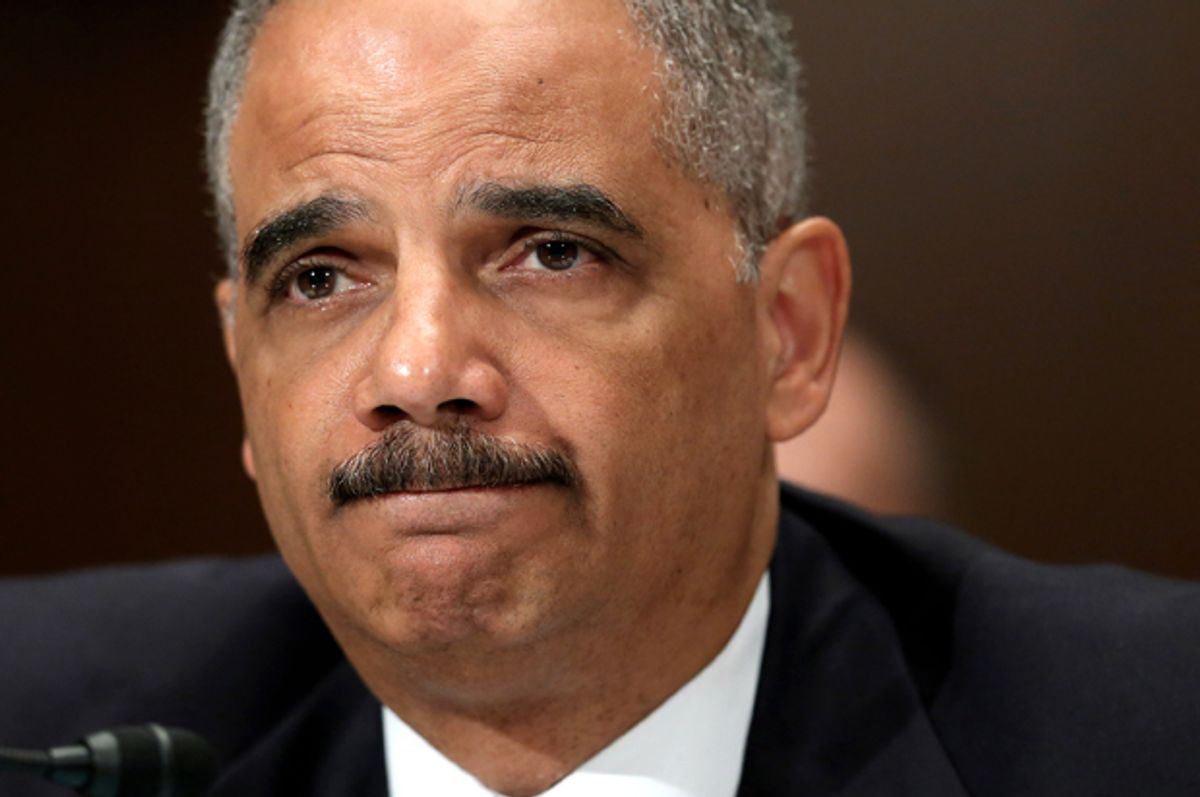

And the documentary extracts admissions from top policymakers of how race has altered our perception of heroin. In a startling scene from the documentary, Frontline correspondent Martin Smith, who is white, asks Attorney General Eric Holder, “Not to be too glib, but isn’t [the new public health response to addiction] because a lot of white kids are doing heroin?” Holder, who is the first African-American attorney general, struggles to be diplomatic. Smith presses him further. “Richard Pryor said, you know, famously—about cocaine—that it’s an epidemic now ‘cause white people are doin’ it.” Holder responds, “There’s an element of truth to that.”

What “Chasing Heroin” wants to focus on, and for good reason, is an initiative in downtown Seattle that is a radically different methodology for handling a massive population of addicts. The program is called LEAD (Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion), and was founded just a couple years ago; it effectively decriminalizes heroin at the discretion of law enforcement, building towards the idea of treating addiction as something other than a crime. For fans of “The Wire,” LEAD’s model feels something like “Hamsterdam,” the policing workaround from the third season that quarantines drug use to a few city blocks to allow the rest of Baltimore to breathe. As productive as LEAD appears to be, it only came to exist after white addiction became prominent. “Chasing Heroin” points out years of Seattle waging war against its addicts of color through brutal policing. Now, all the addicts that the documentary follows to chart their journeys are white addicts, many from stable, middle-class backgrounds.

But in some ways the real story of “Chasing Heroin” is not the somewhat successful story of LEAD but instead the story of little Bremerton, Washington—a town of less than 40,000 just across the sound from Seattle. The first sign of a local problem with heroin was that the town’s toilets were clogged with used needles. A resident describes seeing hypodermic needles in gutters and in playgrounds. But when the mayor tried to open up a methadone clinic—a major waystation on the path to recovery for heroin addicts—Bremerton citizens pushed back. The fears cited were essentially the full gamut of hand-wringing paranoia; Frontline’s narrator diagnoses it, rightly, as a full-blown case of “Not In My Backyard.” But what is truly sad is that the epidemic is already happening in Bremerton’s backyard; the citizens were just blocking the first step towards fixing it. One prominent opponent of the clinic went on to discover that his own child was addicted to heroin.

The Bremerton city council was forced to halt development of the methadone clinic. In the five years since, Frontline reports, 40 more people have died of heroin overdose in Bremerton’s Kitsap County. LEAD lacks resources for its crowd of addicts in Seattle; Bremerton lacks the ability to even acknowledge that the addiction is a solvable problem. Frontline uncovers addicts’ stories that include athletes cooking heroin in a high school bathroom and PTA moms feeding off of each others’ addictions. But all the stories in the world don’t go very far without population willing to accept that this is actually happening to us—to people just like us. Tom McLellan, who served in the Office of National Drug Control Policy along with Humphreys, ended the documentary on a chilling note:

"Society has tried to reduce addiction and the devastating problems that occur. They've tried punishments. They've tried to legislate. They've tried religion. They've tried lots and lots of things. The best by far so far is treatment. We're gonna continue to pay the price for thinking of this as a lifestyle issue, a personality disorder. We're gonna pay that price for a very long time, because it's standing in our way of medical progress, of public health progress."

Shares