Garth Greenwell begins his reading at the Morris Book Shop in Lexington, Kentucky, with the hint of a tremor in his voice. Maybe it’s shyness, or just a slight case of nerves, a response to the emotions of the moment, which must be running high. His sister is smiling up at him from the front row. He’s reading a passage from his new novel that is set here in this state, a place that raises complicated feelings in him. After all, who could blame him? Although Greenwell was born and raised near Louisville, about an hour away, this is only the second time he has returned to his native state since leaving home in the mid-'90s, after his father kicked him out of the house for being gay. But at 37, he has returned triumphant, a sterling debut novel in hand.

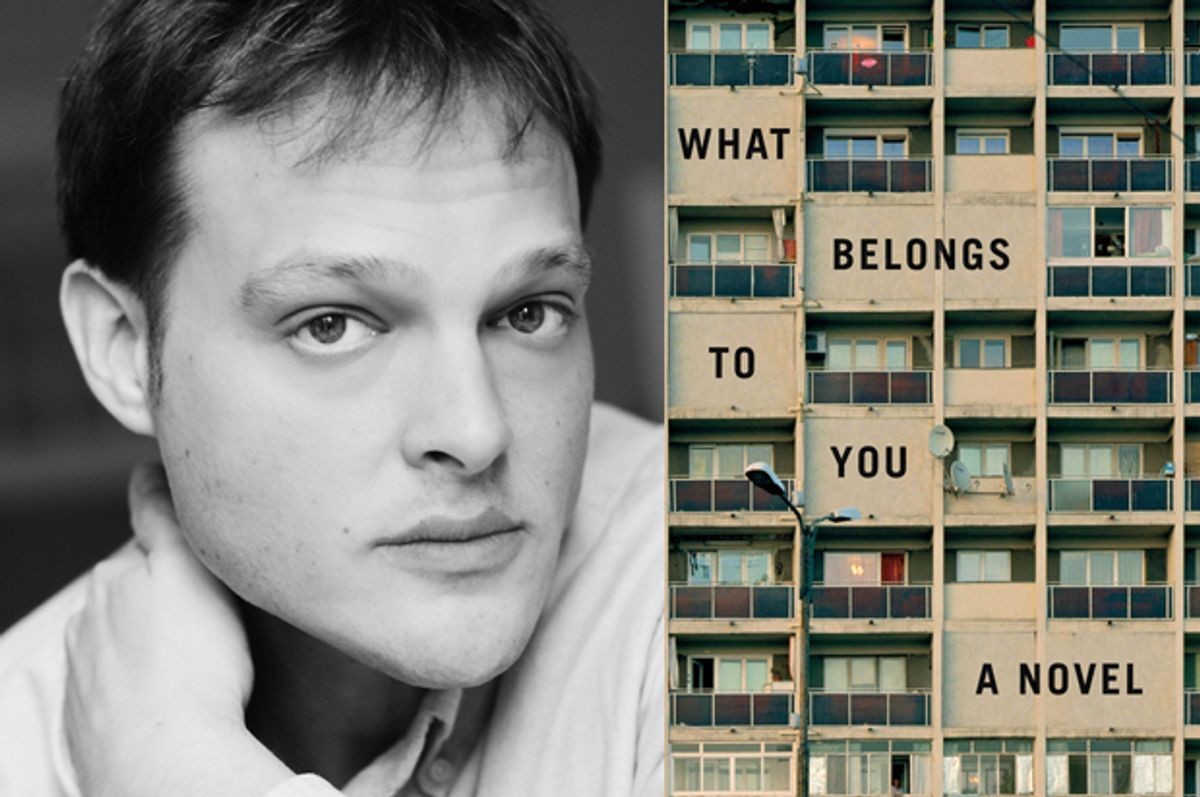

Since its release in January, “What Belongs to You” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) has garnered praise sweeter than a glass of Southern iced tea, heralded as “the first great novel of 2016” by Publisher’s Weekly and “incandescent” by the New York Times. The book opens underground, in a public bathroom beneath the National Palace of Culture in Sofia, Bulgaria, where a young, gay American teacher has gone cruising for sex. He finds what he’s looking for with Mitko, a slender, gritty Bulgarian with “an air of criminality” about him. Mitko charges him for sex, and the narrator is more than willing to pay—again and again as it turns out, setting off a dilemma for the narrator, whose confrontations with desire, loneliness and violence spark memories of his troubled childhood in Kentucky. Written with a poet’s eye for detail in lyrical, looping prose, “What Belongs to You” explores how the scars we carry from childhood can wreak havoc in our lives, as well as create startling possibilities.

“What Belongs to You” is set in Bulgaria, in Sofia, where you lived for four years. How did being in that city—being a foreigner, having to grapple with a different language, new customs—help to inspire the novel?

It was my first time really living abroad. I had only spent a few weeks one summer in France before that. I had never been to Eastern Europe, and so I think I was really kind of overwhelmed by the strangeness of it. The most powerful response I had to the place was that I fell in love with the language absolutely. I think it’s the most beautiful language in the world, and I loved speaking a language other than English every day. And on days that I didn’t teach, or when we were in break or on vacation, I would go days without speaking English, and that really did change my relationship to English and change my relationship to the act of writing. It made my writing more private...I don’t understand why this happened, but somehow being in Bulgaria made me write prose. I had only written poetry. I did an MFA in poetry, I was really attached to an identity as a poet...I had never studied prose, and I had no workshop voices in my head when it came to prose...The sort of metaphor I use is I really felt like I was like inching forward in the dark, kind of clause by clause, just writing a sentence...

The real spark of the novel came from [being] in Bulgaria and meeting gay men in the kinds of communities I found [there], which were these cruising bathrooms and places, [and I realized] that men were saying to me the same things that men in those kinds of places said to me in Kentucky in the early '90s. And also I was working as a high school teacher [at the American College of Sofia]...I was the only openly gay person in the school community, I was the only openly gay person almost any of my students had ever met, because all of my students were Bulgarian...That meant that all of my students who were queer, who thought they might be queer, came to talk to me, and they told me stories that, even though they were in this foreign landscape and this culture that's very far away from the culture of Kentucky, I felt like they were telling me my own story. And I felt like both the adult men I was meeting in bathrooms and then my students who were coming to talk to me [had] exactly the same horizon of possibility for their lives that queer people in Kentucky did in the early '90s.

The first section of the book was originally published [by Miami University Press] in 2011 as a novella titled “Mitko.” When did you realize that this story wasn’t done with you?

In the first section of the novel, Kentucky’s not really at play. But there are two things that I didn’t really understand why they had to be in that first section...One of them is that when Mitko says that he works construction—the narrator doesn’t speak Bulgarian very well and Mitko doesn’t speak any English, and so he like acts out these construction things—and the narrator thinks of his father, because his father worked construction one summer. And then I thought that’s weird. I remember questioning it because there’s nothing else about the father in that section...And then the other thing is there’s this weird little scene [in which] the narrator sees this little girl playing with her father by a river in this mountain town. When I went into revision mode, I tried to convince myself to take that out because it just doesn’t make any sense in that first section, but I just knew it had to be there. I couldn’t take it out. And it wasn’t until I was halfway through that second section which I had not been planning to write—the one set in Kentucky and all one paragraph and very much out of control—that I realized...those things that were so confusing in that first section were like seeds set for this, and really preparing the way.

But I really didn't think of it as a novel until I finished all three parts...I never had any idea of the shape of the whole thing until maybe I was halfway through the third section, and then I started consciously doing some things to try to make it cohere and give it some kind of symmetry. When I finished it, I looked back over this thing and I thought...it feels like a novel. But it took a long time for me to trust my intuition that there was this kind of gravity holding these parts together. And to a certain extent I had to have other people point out some of those things and the way that there are these echoes. And then I read a book that was...revelatory for me—David Galgut's “In a Strange Room,” which has these three disconnected, or not obviously connected, narratives. And I read that book, and I just thought a novel can work this way, and the gravity holding these parts together doesn't have to be a kind of obvious narrative logic.

It sounds like your being a poet and coming at it from that [perspective]—rather than knowing the rules of prose—was liberating.

I think it really was. And that was true [because] I was just so overeducated in poetry. I had an incredibly privileged education in poetry. I got to work with extraordinary poets who've just filled up my head—their voices filled up my head, their advice filled up my head. I studied poetry in the Ph.D. program at Harvard for three years as a scholar, and...memorizing poetry is something I do. And all of that just went away with prose. At the same time, though, I do think this is really like the novel a poet writes. I mean, to a certain extent I feel like every scene is this sort of lyric moment. I feel like the book is really interested in those moments where time thickens and slows down, and it's interested in excavating moments in the way that lyric poetry does. Sometimes people read the book and they're like, But there's basic information we're missing. And I think one reason that I was really comfortable with that was just because when you deal with the lyric subject, you're just not burdened with that information. And so the fact that I hadn't studied fiction meant that I just didn't know enough to miss a lot of that stuff—which is a way of saying that when I first wrote “Mitko,” I had this very powerful feeling of This is just better than anything I've written, and it's better than any of the poems, and it just demolishes the poems. And that was really upsetting to me, because I had invested so much in thinking of myself as a poet. But to a certain extent, the lines between genres don't seem always all that meaningful to me.

Part of the book obviously focuses on cruising, which historically [is related to] society's rejection of gay men. But in a lot of quarters of mainstream culture, that is looked down upon as lewd, as dangerous. What made you want to explore that on the page?

Those communities—and I do think that's the right word for them, community—have been central to my sense of [self] since I was 14 years old. And to me, they seem like extraordinarily rich places, and places where people have extraordinarily rich encounters of all kinds. And some of those—as in any other human space—are negative or painful or damaging, and some of them are intimate and sustaining and I would say loving. And I want to write about those communities and those places in a way that recognizes that richness and [where] the whole gamut, the whole range, of human feeling and of human ethical response is at play. And while it may be true—although I also think it may be too simple to be entirely true, to say that those places came into being as a response to the fact that sort of other kinds of spaces were closed off to queer people or were limited to queer people—they haven't disappeared.

They are spaces that should be valued, because I think...a lot of what is potentially radical in queer identity and queer life comes to the fore in places like these. Because in these places, all of the usual categories by which we organize our lives—like race and class—get scrambled. This is one reason why desire is always causing trouble. Desire just scrambles those things. People have encounters in these places that they wouldn't in other spaces, and any time those kinds of encounters happen I think there is the possibility for that kind of spark of empathy. It's not to say—I mean, I don't want to romanticize these places. They are places where people are exploited and assaulted and all of those things, but they are also places where I think there is the possibility of an empathetic response and of a compassionate response across the kinds of divisions and rooms of privilege and class that keep us separate. And you know, there's something that I fear in the marriage equality sort of version of queer life that is dominant right now in sort of the American public consciousness.

We've obviously seen a lot of gains in our country—

Absolutely. No question.

—with marriage equality being the most recent—that [have helped] bring the LGBTQ community into the mainstream. But do you think that we're also losing some things that have helped to define gay culture in that process?

I think there's a risk of that. I 100 percent [believe] marriage equality is important. I think it was an important battle. I'm really glad we won the battle. I think it's tragic that we won that battle at the cost of so many other battles that we need to fight. And I think it's tragic that we won that battle at the cost of further marginalizing the most marginalized parts of the LGBTQ community...That was a battle fought in the language of advertising. And when you look at those advertisements, the people in them are almost all affluent, they're almost all white, they're almost all of a certain age, they've almost all organized their lives in a kind of model that looks very heterosexual to monogamous people who have formed a relationship around the raising of a child. And that is an important model of life that should be open to queer people, and queer people should have the rights and responsibilities that come with that model of life. But that is not the only model of life, and that is not the only model of queer life, and to the extent that the battle for marriage equality meant pushing those other models to the side and kind of disavowing them, I think that [is] unpardonable. And I do think there is a risk that that radical potential of queer life can be lost if the only model our community recognizes as legitimate is a kind of heteronormative model.

I mean, look—one of the great and terrible accomplishments of America today is that we have so carefully separated the rich and the poor. And those other models of queer life were places where that division got scrambled, and where queer life kept its contact with the culture of poverty, and I think that's really important...I have really strong feelings about these places and that they are valuable, and that even if they did come into being as a response to shame...they are also places of joy, and they are also places of compassion and of something that I would call love and of intimacy... There's just something intensely radical in having this extraordinary intimacy with a stranger, and with someone who's not just potentially unknown to you in your everyday life, but someone who belongs to categories that your life is structured in a way to avoid or to keep you from. To me, we should not be dismissive of the ethical potential of that.

A lot of this, I think, revolves around [this idea of] what a gay person looks like, who a gay person is. By a lot of people's notions, gay people only live in cities—

Absolutely.

—when we both know that there are plenty of gay people growing up in rural areas that have an experience that looks different.

And those stories have not been told. And I really think that my next novel project is going to be set in Kentucky, and I want to sort of think about those communities that were so important to me when I was a kid and the stories of the people I met and the friendships I formed. But what you say is so important, because I think it's true that people think about queerness as kind of an urban phenomenon...Because there was this sort of overly facile attack on marriage equality that was this is just about gay white men—this is about the most privileged part of the queer community, this is about gay white men living in urban areas—

With tons of disposable income.

And that's just bullshit. Because we know that in fact the majority...of queer families with children are not in those urban [areas], that in fact they're in the South, that many of them are in rural populations, that many of them involve people of color. And you know, marriage is incredibly important for those families. And marriage is incredibly important for sort of day-to-day life on the ground, like feeding my kids, protecting my kids, protecting my spouse. And to sort of deny that and say this is just about rich white guys, that's just false. At the same time, you know, gay kids are still dying on the streets, and gay men are still dying of AIDS—

Getting kicked out of homes—

Getting kicked out of homes, and those are vitally important issues for the queer community to address.

I was very moved and intrigued by how you write about touch. It appears throughout the book, obviously in sex, but also in other situations and places...I think of that passage on the train with the narrator and his mother [watching] the grandmother and grandson, the boy “draped across her lap, his arms cast about her, a posture so sweet it was almost painful to see, as it was painful to see my mother, who watched them with such longing I had to look away.” [I’m wondering] how you’ve noticed the concept of touch changing as you’ve gotten older, because I think that [theme is] there in the book.

That's such an interesting question. I'll start by saying that it was a reader who pointed out that there is this pattern of scenes where there are...often non-sexual embraces. That's one of the echoes throughout the book. And I thought, right, because this is a narrator who has real issues with intimacy. This is a narrator that is in a lot of ways distant, and who feels in a lot of ways really locked away from other people, from himself...I feel like the narrator imagines that there was a time when intimacy was kind of the air he breathed, and childhood [was] that time. And these moments that he has with K. [a character] or with Mitko...or that he projects on to what he sees with that girl by the river and with that boy on the train—it's like they gesture to this world he has been shut out of completely. And maybe it's true that—just shifting from the narrator to me—as an adult that sense of being excluded from that doesn't feel so absolute...

As I get older more things seem possible to me, in my own potential for response, which is a great gift of getting older. There were stories about myself and about my life I took for granted for a long time, and maybe those stories are finally less determinative of my life than I thought they might be. For me—for my experience growing up in Kentucky as a gay kid in the early '90s—I really felt like I was taught one lesson about my life and that was the lesson that made it really hard to live. And even as I have moved away from that—and even as I have taught myself other lessons [and] been taught other lessons—I feel very painfully the fact that you never get to be the person who didn't learn that first lesson you're taught about yourself. You can learn other lessons, but you never get to not have learned that first lesson. And as I get older I do feel like, well, maybe that hasn't shut as many doors as I...thought. Maybe that's just wishful thinking. But it's interesting that that kind of hope is available to me more now than it ever has been.

We're both from Kentucky [and] grew up in different parts of the state around the same time, but in a time and place where being gay was scorned, and it was connected certainly with AIDS. How did this place both create and damage you?

Oh. Lord. [laughs] In an earlier interview, a guy asked me, “Do you think of yourself as a Kentucky writer?”—because at this point I’ve spent more of my life away from Kentucky than I [have] lived in Kentucky. And I just hadn’t really thought about that question before, but I just immediately said, “Yes, of course, absolutely I am.” And that’s true...I sort of feel like everything goes back to this place. This was the place where I learned those lessons that to be queer meant your life had no value. To be queer meant that either you never had sex or you got AIDS and died and you were punished. This was the place that shaped my father, and shaped him in such a way that when his kid turned out to be queer he said, “Well, you’re not my kid.”

This was also the place where—it was in Kentucky public school that I discovered art, and the choir director, David Brown, really saved my life by showing me what art was and how art can be an escape. It's where I found cruising and came into my first understanding of myself as a gay person and first experienced the joys of being a queer person, not just the trauma of being a queer person. Everything I am is this place, really. And also the landscape of this place—just driving [the other day] I had to pull off the side of the road and look at how beautiful this place is. My ideas of beauty go back to this place...The only other place that has had kind of similar impact to me is Bulgaria, and...I think the reason I had such a chemical response to Bulgaria was because of all the ways it reminded me of Kentucky...Everything goes back to Kentucky. There's no question. For better and for worse.

Sex is obviously a big part of this book, [and] many of the reviews and coverage have focused on that. I read one of the headlines the other day that said "Garth Greenwell on writing sex."

Yeah. [laughs]

And so it's an important part of the book, but it's not the whole book.

It's not the whole book.

There's a deep family story here. You [compare] two regions of the world that feel familiar. Has any of that coverage and focus been a bit annoying? Do you ever get the feeling that it's being focused on because it's gay sex?

That's a really interesting question. You know, it hasn't annoyed me, and one reason it hasn't is that it has just been amazing to me that a book in which [queer] people [and queer sexual bodies] are central—I mean, there basically aren't straight people in this book for straight readers to identify with and emotionally invest in—it's just been the biggest surprise of my life that this book has been received as it has been. Those are things that often keep books from...being seen. I guess I kind of welcome that discussion of sex in the book...Writing sex is really important to me [because] when you write about something, when you make art out of something, you’re making a declaration. And that declaration is that this thing has value. And it’s certainly the kind of book that I’m writing—that this is beautiful. Even in our world of marriage equality, that is not something we can take for granted when it comes to the queer body and to queer sex.

To a large extent, the push for marriage equality has been about convincing people who are disgusted by gay people that gay lives have value. That is such an important message.

Gay sex remains something that our culture thinks is dirty. And queer bodies are despised, and especially queer sexual bodies are despised, and we're told that they're dirty, and we're told that they're diseased. And to write them in a way that I hope—I mean, to the greatest extent I'm capable of, that uses the full resources of the English literary heritage, that uses all the resources of lyric poetry—to say this has value, this is beautiful, this belongs in art—I think that's really important work for queer writers, for writers, to do. It’s one reason why I feel so inspired by somebody like [novelist and memoirist] Lidia Yuknavitch who is putting sexuality—and not just sexuality, [but] acts of sex—front and center in her books in a way that says very clearly I am not interested in making this acceptable to you. I am not interested in turning you on. I am not interested in making you feel comfortable—that's not what this book is going to do. I hope that my book makes similar declarations.

Shares