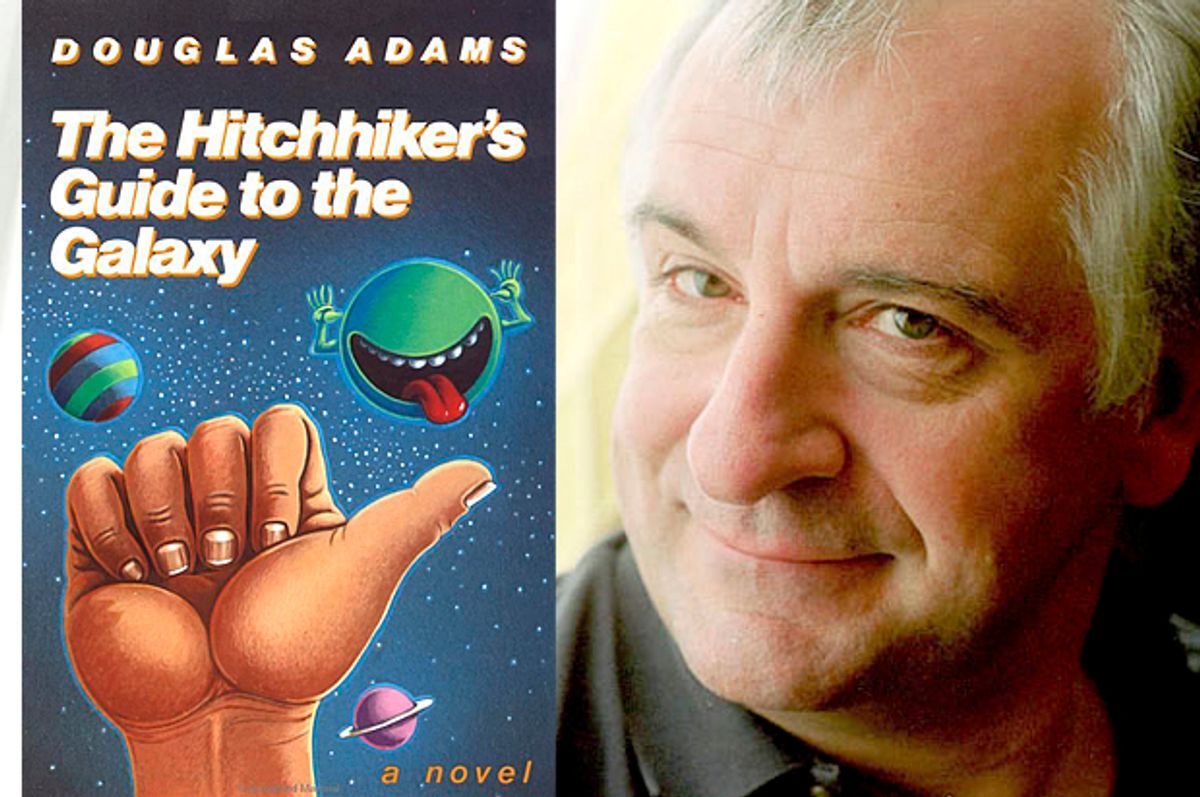

The British novelist Douglas Adams, best known for “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” would have been 64 today. (He died in 2001 of a heart attack.)

Today – 15 years after his death – thousands of tributes to Adams are circulating on social media. His work was beloved by fans of science fiction and comic writing, by atheists and environmentalists, and by nearly everyone, it seems, who found his novels at an impressionable age. These are the kinds of books which, encountered in the right way, could turn someone into a lifetime reader. And the televised adaptation of “Hitchhiker” spread his work far and wide.

With two U.S. presidential debates this week, and general incredulousness at the options – Democrats can’t believe the Republican slate, and vice versa -- it’s not surprising that the most visible Adams quote today seems to be one about presidential politics. Adams' lines from “The Restaurant at the End of the Universe,” the second of the “Hitchhiker” books, have become ubiquitous:

The major problem—one of the major problems, for there are several—one of the many major problems with governing people is that of whom you get to do it; or rather of who manages to get people to let them do it to them.

To summarize: it is a well-known fact that those people who must want to rule people are, ipso facto, those least suited to do it.

To summarize the summary: anyone who is capable of getting themselves made President should on no account be allowed to do the job.

(Adams, though English-born and Cambridge-educated, spent his last years in the United States; he died outside Santa Barbara.)

It’s worth asking: Was Adams political in any orthodox – or unorthodox – way? And what would Adams make of the American political scene these days? Did he dislike both sides of the aisle politically?

Adams seems to have been like a lot of writers: He had some causes, but he did not seem to have strong political allegiances outside of them.

In “Hitchhiker’s Guide,” for example, he came up with one of the most elegant expressions of a kind of happy atheism crossed with his own love of the earth: “Isn't it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?”

(The Douglas Adams Memorial Lecture is held each year to support Save the Rhino and the Environmental Investigation Agency. Neil Gaiman spoke last year, and the latest, given this week, saw British scientist Alice Roberts speaking on “Survivors of the Ice Age.”)

In the current U.S. political climate, the religious skepticism and environmentalism would have placed Adams in what we think of as the left. But he was also skeptical of labor unions. And the beginning of “Hitchhiker” sees Arthur Dent’s house on the verge of being demolished for a highway bypass… just before the earth is destroyed for the sake of an interstellar bypass. This sounds like someone a bit frustrated with government action who could have easily drifted into a slightly liberal stripe of libertarianism if he’d lived long enough.

Adams would likely be bewildered by the truculence on the political right these days; he was, by all reports too gentle a soul to respond to Donald Trump’s nastiness. But he was also skeptical of socialism and some strains of contemporary thought that have only grown since he was young. One of his mentors at Cambridge was George Watson, a philosopher who was in most ways a centrist and in some ways resistant to academic leftism. “During the great upheavals in English studies of the 1970s and 1980s,” according to one of the professor’s colleagues, “Watson was firmly in the traditionalist camp, with little time for relativism and none at all for deconstruction.” It's hard to imagine Adams being any fonder of them.

“For Adams environmentalism trumped party politics, especially in his later life,” British scholar and science-fiction writer Adam Roberts told Salon in an email. “He was from what you might call a soft left UK intellectual milieu, but he didn't publically align himself with either the left or the right. If you read his books, he's as likely to satirise the union-troubles of 1970s Labour as he is the rampant commercialisation of 1980s Thatcherism: but what really mattered to him, politically, was whatever would conserve the environment, preserve species diversity and so on.”

Science fiction writers are often all over the place politically. Philip K. Dick was a paranoid who mocked consumerism and feared the government. Robert Heinlein was a socialist early on, but became more and more admiring of the military as a model for civilian life. Part of me would like to claim this atheist and environmentalist for the left. But it’s not quite true. And compared to those two other authors, Adams’ general skepticism towards everything he wrote about seems sensible indeed.

Shares