“TURN ON FOX NEWS RIGHT NOW. YOU’RE THE NATIONAL LEAD.”

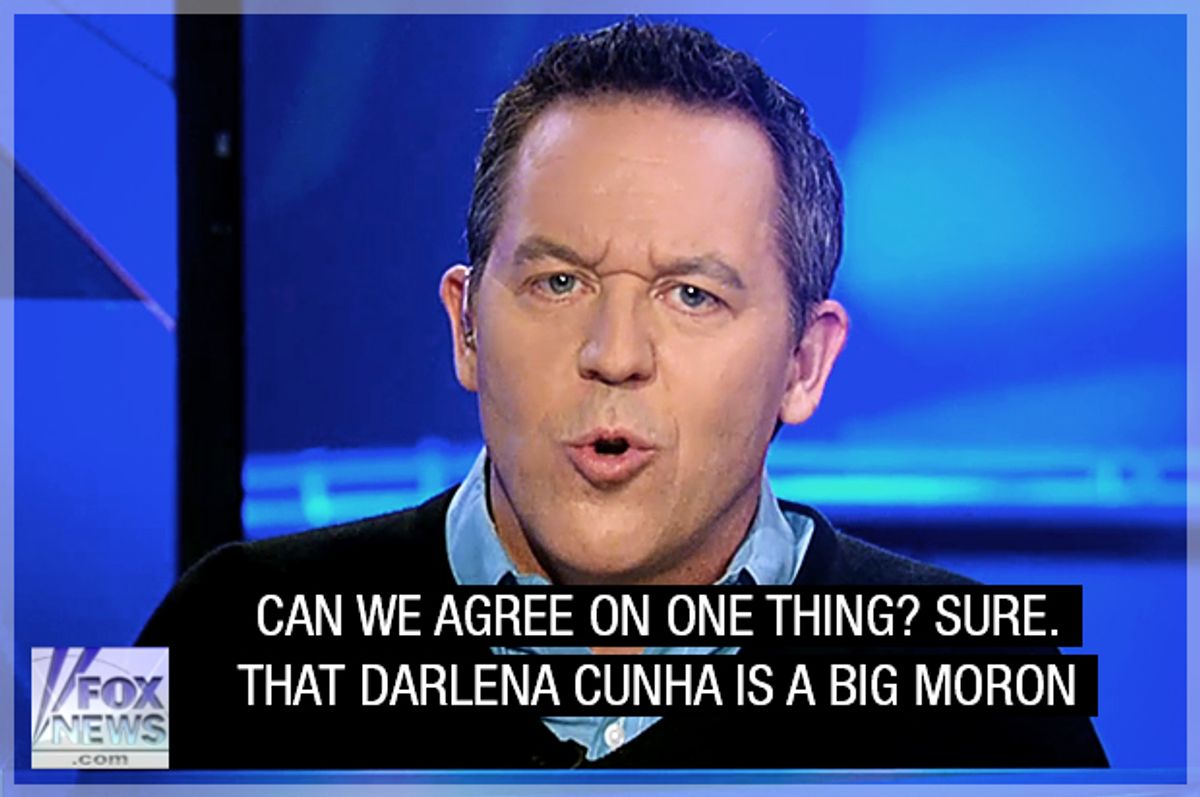

It was Thanksgiving weekend, 2014. The smell of the candied yams permeated the house while my mother rolled out pie crusts and I argued aloud with the turkey recipe. Amid the bustle of dinner preparations, my computer sounded the notification bloop for Facebook messaging and I saw the message from my friend. Sure enough, I turned on the television just in time to hear one of the hosts say, “If nothing else, I think we can all agree that Darlena Cunha is a moron.”

I’m a writer. I freelance for various publications, spouting out my opinion and backing that up with facts and statistics. I get paid to show readers a viewpoint of society through a lens of progressive ideals. I get paid, essentially, to make Fox News mad. In this instance, I had written a piece for Time magazine, titled: "Ferguson: In Defense of Rioting." I wasn’t really playing the moderate. Throughout my career, I’ve made any number of readers angry, and those readers have lashed out, calling me stupid or whiny, or expressing sympathy for my children. Given that, the name-calling from Fox didn’t surprise me. I was, however, taken aback by what followed. Everyday trolling is one thing. Part of my job is to shoulder criticism, and take in what’s valid, leaving the rest on the commenting forum floor. Actual intimidation, stalking and threats, however, are a totally different—and potentially deadly—game.

The difference between national news organization trolling and your garden-variety Internet troll is that the offshoot articles these companies produce become the starting point for the troll army—so that many times a troll never even reads your original work before spouting off. No matter, though, trolling is trolling and primary sources are not required.

But to me, a writer forced to put my name and social media handles on top of every piece I write, trolls can be dangerous. They can be scary. I’ve learned to deal with the hundreds of comments calling me names after I publish a piece, but it’s a different story when comments read like threats. My first published piece, for instance, was a researched personal essay about the time I had to drive my husband’s Mercedes to pick up coupons for Women, Infants and Children—a social service for those facing low incomes. Through that piece alone, the general public knows intimate details about my life. And some of them carry it with them. They follow me from piece to piece.

Not long ago, for example, I received this comment by TomSmith6. He was commenting on the Ferguson piece, but bringing up details from my original essay.

“Easy to say as she drives her Mercedes and watches it all unfold on TV from her 1%-er Florida suburb. Bring the action to her town, to where her kids live/play/go to school. Bitch be singing a different tune. Shoot them all.”

Then he gave out as much personal information as he could, so that people could attempt to find my home address. I had to wipe my Internet presence and ask my publications to take any reference to the town in which I live off my bio. Just in case. Because while most of these comments are all just smoke, you never know which one guy is actually serious.

But there was another time in particular, that stands out from all the rest, a time when I felt completely powerless to protect myself. A time before I’d even chosen public writing as a profession.

His username was Promeny, and we were in a Livejournal community. The persona he presented online was that of a young man, utterly disgruntled and disgusted by women who continued to scorn him. Promeny took the hatred he’d been feeling for himself and women in general, and turned it on the specific women of the group. It would usually start with a post where he would ask the group for advice, something about how to talk to women without scaring them off, for example. A good example is this, posted in April of 2010, “I’ve wandered the nation. No one likes me. No girls. 26 and a virgin.”

The women of the group felt sympathy for him, and began giving suggestions freely. “People can be so mean. I know you will find someone soon, and, trust me, being a virgin is a million times sexier than being a ‘manwhore’ or whatever.”

To these comments, he’d respond with bristle. A woman suggested finding someone who just wanted to have fun to get it over with, and Promeny replied that he would only touch a woman he loved. Then he complained about all those women having boyfriends. He was consistently "friend-zoned."

As the conversations continued, he became more hostile. Eventually, his nice-guy act fell completely away and he began berating the very women who had been trying to help him. They became cold, manipulative sluts in his narrative—another score of women who wrongfully underestimated him, even though they had done nothing of the sort.

Having been a part of that group since its inception, and being older than many of the women there, I felt compelled to step in to call him out on his atrocious behavior. While there is no such thing as a safe space on the Internet, I mistakenly thought we could all just try to be civil. Having not engaged any critic or troll on an emotional level before, I didn’t realize what I was getting into. These days, of course, I rarely comment at all. My writing stands for itself. But back then, I started by calmly showing him how what he was saying was both untrue and offensive, and went on to try to explain how pulling out attitudes like that may be part of what hinders him in terms of women.

He attacked me, calling me stupid and a bitch. I realized I had sent myself on a fool’s errand, and instead of continuing to try to reason with him, I started replying to his continuing diatribes with gifs and macros. Remember, this was 2010. If I had to do this over again, I would not have encouraged his anger by posting smarmy pictures in reply. Looking back, that was mean. It was not uncalled for, but it is not the kind of person I want to be known as. And unlike me, Promeny was not having fun. The pictures, apparently, were all it took to put him over the edge.

I don’t know what I expected. Perhaps that he would leave quietly with his tail between his legs, or explode in a fiery waste of words before taking his ball and going home. Whatever I expected, it wasn’t what followed.

“I’m going to find you, and one night, while your children are sleeping, I’m going to cut out their tongues and gauge out their eyes, so they can bleed to death, mute and blind.”

It was the first death threat I’d ever received, and it involved not me, but my children.

I scrambled. I was scared. I contacted Livejournal, hoping they could suspend the user, or dole out some consequence. They refused, stating that the best course of action would be to let him be, without reprimand, that to follow any other course could lead to further animosity and danger to me. If he remained in the system, they reasoned, they could keep an eye on him and monitor his remarks.

Without Livejournal on my side, I called my local police department to try to put on file that there had been a threat made toward my family. They listened politely, then told me there was nothing they could do.

Years later, I can see why. If every woman called the police on every anonymous threat to her family, the police would have time to do nothing else but investigate these cases. According to the Pew Research Center, 26 percent of young women on the Internet have been stalked, and 23 percent have been physically threatened. Of all people who have experienced online harassment (40 percent of all Internet users), 26 percent did not know the real identity of the perpetrator. While there are currently cyberstalking laws, they are hard to enforce, and victims must know their harasser’s identity to take him to court. And in 2010, those laws didn’t yet exist at all. The police told me there was nothing they could do. With no other recourse, I started checking on my children two or three times a night, waiting for an attack that never happened.

Eventually, Promeny disappeared. I recently searched for him, and the journal no longer exists. He never bothered me again. It really was just a one-off, a fantasy he allowed himself to type out and send across the country to a real person with real children.

The difference between the rape and death threats I receive nowadays and that first threat all those years ago is very simple, and very important.

Back then, in that specific instance, I was Promeny’s main audience. He was talking to me. Trying to scare me. He was looking at no one other than me.

In comment sections and message areas these days, I am not the audience. Every person calling me a moron, or wishing “a dystopian hell upon my unfortunate spawn” isn’t talking to me at all. They aren’t trying to scare me out of writing, or truly threaten my well-being. They are talking to the other commenters on the page, showing off for them. It’s as if you are at an endless holiday dinner with all your conservative uncles, half-drunk around the dinner table, still trying to impress Johnny, the next-door neighbor who used to be the football champion of the high school back in ’72. They might be ruthlessly making fun of you, even bullying you, but you are not the object of their efforts. You could just as easily be a cardboard cutout and they’d not know the difference.

Ultimately, there is a substantial difference between trolling that is meant as a performance and trolling that is meant as an attack. Being the object of trolling is part of my job—it’s irritating and obnoxious, but par for the course. People have things to say, and I make a good scapegoat for their angst. Being the subject of trolling, however, where the words are meant to harass and intimidate, is scary. It’s dangerous. And attacks like that hurt not only the writer but the public, as well. When trolls make writers their true target, they block free speech, not by censorship, but by intimidation.

These days, I consider having to deal with incessant attacks on my person as part of what publications are paying me for. The attacks certainly aren’t going to stop me from writing any time soon. Still, for all this bravado, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t worry every single time a piece goes live—about my family, about my livelihood, about my reputation, about my very safety. So, in a way, they’ve won. Because what is a game to them truly is my real life, and I have nowhere to hide.

Shares