I'm not going to tell you to go right now and buy a copy of Peggy Orenstein's "Girls & Sex." I'm going to tell you to buy two copies: One for yourself, and one for the teenager in your life. Because kids — boys and girls, gay and straight — need to understand not just what a new generation of girls is doing in its intimate life. They need to know what those girls are not doing. Like when they're not saying no to stuff they're not into, because it's easier than arguing about it. Like when they're not asking themselves what feels good — for them. And it's high time, in a cultural moment fraught with sexual panic about hookups and sexting and questions of consent, to shift the conversation — and to fight for young women's right to orgasm.

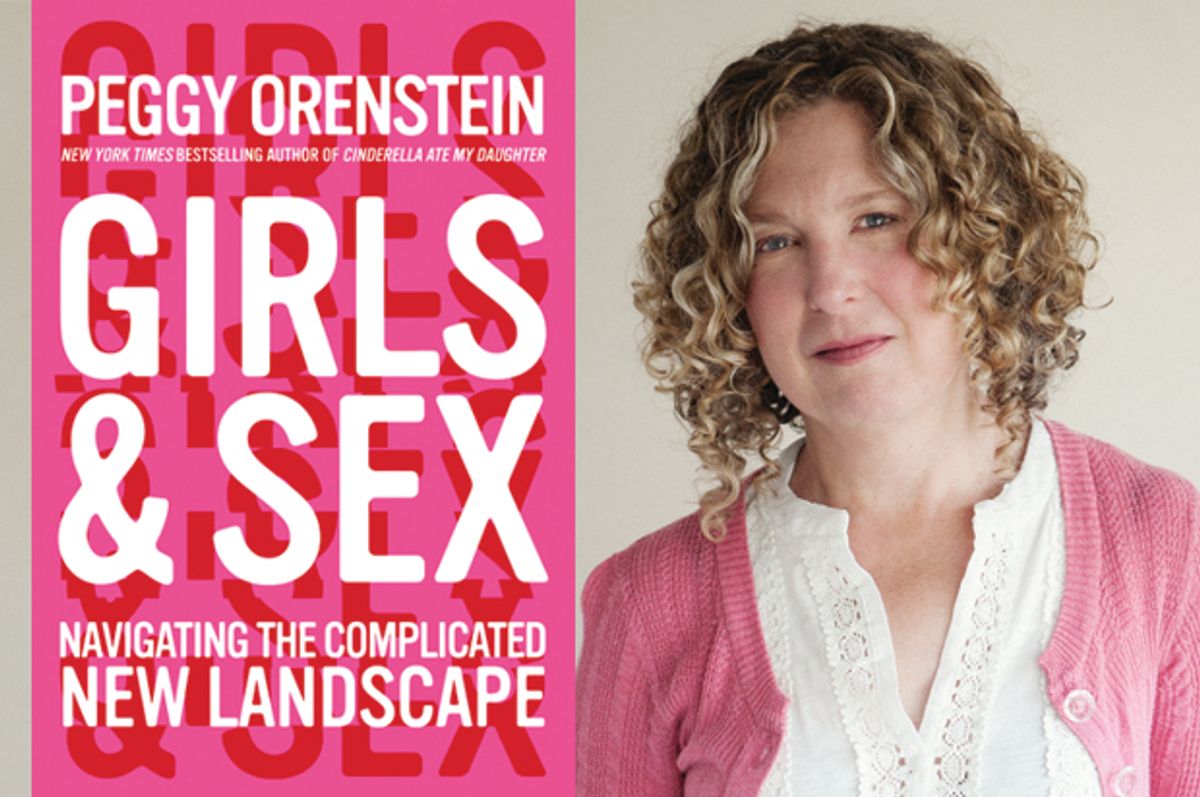

Peggy Orenstein is a uniquely qualified advocate. As she told me recently in a raucous, "Crazy Ex-Girlfriend"-referencing Skype session, "I feel this really intense connection and resonance with girls. I love talking to girls; I love hanging out with girls. That's why I keep coming back." That she does — Orenstein has spent much of her journalistic career in girl world, from 1994's "Schoolgirls: Young Women, Self Esteem, and the Confidence Gap" through her 2011 bestseller “Cinderella Ate My Daughter."

It's been five years since Orenstein's bold, hilarious and occasionally terrifying foray into the princess industrial complex. Now, the same girls she wrote about then — including those high heels-wearing baby divas — are hitting puberty and beyond, and Orenstein is back to see what happens after growing up with "that 21-piece Disney princess makeup set." Her newest book is an exploration of the lives of high school and college-aged girls today, shown through their various forays into purity balls and walks of shame, into hooking up and coming out. It is not, refreshingly, a condemnation of millennials and their successors — or a hand-wringing call to alarmism. Yes, it discusses frankly the often performative aspects of female adolescent sexuality and doesn't ignore the realities of sexual assault, but "Girls & Sex" refuses to be judgmental or doom and gloom. Instead, it offers something else — a demand for education, enlightenment, and ultimately, the radical notion of equal satisfaction.

When I got your book, I got a copy for myself, and one for my teen daughter. Now she's passed it around among her friends and is having conversations with them. Did you imagine it would be used that way?

I keep hearing that, and that's exactly what I'd hoped. Generally what happens with my books is that the first line is parents, but that it quickly migrates to high school girls and college girls. They can just read it themselves and talk with their friends. It gives them information. And that's power.

I thought, I'm going to give this book to my daughter the summer before she goes into ninth grade. I wrote it because my daughter's going to be going to a gigantic high school where all bets are off and I was hearing a lot of stuff from my friends whose kids go there. I thought, I need to understand this, and I need to make the world better before my kid gets there.

One of the things that bums me out is seeing young girls who can be so empowered and forthright everywhere else, and then in private they don't even know that they're allowed to want things. They're giving sexual favors and getting nothing in return. You talk about how revelatory it is for these girls when they have an orgasm.

Yeah. One of them said, "I cried. I cried." I mean, that's amazing.

One of my favorite stories is talking to girls about the nonreciprocal thing and saying, "What if guys asked you to get a glass of water, over and over, and they never offered to get you a glass of water? Or if they did, it was totally begrudging?" They would laugh. It's less insulting to be told that you're never going to have reciprocal oral sex and you're always going to be expected to go down on a guy than get him a glass of water.

But we set girls up for that from the get go. Everything in the culture tells them that they are supposed to perform, that they are supposed to pay more attention to being desirable than their own desire. We don't as parents name that whole area between belly button and knees. We don't tell them what a clitoris is. We don't even tell them what a vulva is. We just avoid the whole situation.

[Kids] go into puberty ed class, and female pleasure is not necessary to talk about when you're talking about reproduction. So we don't. We talk about periods. We talk about unwanted pregnancy. And with boys we talk about erections and ejaculation. Then, no surprise, only a third of girls masturbate regularly, only half have ever masturbated. And then we tell them to go into their sexual encounters with a sense of equality. How is that supposed to happen?

We have completely shrouded them. Maybe they figure it out. Maybe they do. But maybe they don't, or maybe they have to get over their early experience, and that's wrong. Look at research: When we talk about sexual satisfaction, we're not talking about the same thing. Young women tend to measure sexual satisfaction by their partner's satisfaction — which is why lesbians are more likely to have orgasms. They're like, "I want you to feel good! No, I want you to feel good!" Heterosexual girls will say, "If he's satisfied, I'm satisfied."

Boys are more likely to measure sexual satisfaction by their own orgasm and their own pleasure. On the flipside, when they talk about bad sex they use completely different language. Boys will say, "I didn't come or I wasn't that attracted to her." Girls will talk about pain and humiliation and degradation. Boys never use that language. We're talking about really different experiences going into it. That's why I love that term "intimate justice." To think about this in terms of equity and power dynamics and who is entitled to engage sexually. Who is entitled to enjoy? Who is the primary beneficiary?

So what is different now? What is it about this generation that is not just historic "girls pleasing boys" crap that we've all gone through?

Some of it is the same. When I think about that I think, why is it the same? When girls are so much more empowered, when they are so much more vocal — why have things changed so much in the public life and not in the private life? I think all of those things that have grown more intense in an age when the culture has grown so visual and so focused and even more saturated in sexuality. You have a hookup culture where sex precedes intimacy rather than the other way around. And that's not saying, "Only have sex in relationships," because that's not true. It's not a moral judgment. We're not saying, "Oh heavens." We're saying, what are you getting out of your sexual experiences? What do you want to get from those experiences? What are you entitled to, and how do you get there?

What I wanted to do is say, this is what it looks like. This is what you'll probably get out of it. This is what you won't get out of it. Once you know all that, you make your informed choices. Otherwise, the choices are just presented by the media and it's like, we rip off half our clothes, we have intercourse with nothing preceding it. We both have orgasms in three seconds and it's great. Then real girls go into real encounters and think, "What's wrong with me?"

When you have not even yet had your first kiss, nobody says to you, "It's a symbolic repression that if acted out isn't going to feel particularly good for women." That's part of trying to normalize conversations around sex. It's not about "the talk" when we've never told them they have a vagina and now we're going to tell them about reproduction. That's about talking about these ideas about rights and entitlement in sexual relationships.

You make it clear that kids who have abstinence-only education are going to have sex pretty much at around the same time their peers are and they're going to do with less protection. So what can we learn from religious conservatives about what they're doing right?

I went to a purity ball in Louisiana. I feel like it would be really easy to go to one of those things and just slam them, because the idea behind them is completely wrong. Kids are not going to abstain. We know that maybe they delay sex a little longer. But they have greater rates of pregnancy, they have way higher rates of disease. The boys are six times more likely to engage in anal sex and both boys and girls are more likely to engage in oral sex and not see that as compromising their virginity. So we know that that's really crap.

That said, there was something really moving about the event, and seeing that the fathers there were having this conversation about their values around sexuality and their expectations around sexuality and their hopes around sexuality with their daughters. It wasn't the conversation I wished they'd have. But when I talked to the girls who were from more typical families, if I asked what their fathers said to them, they just laughed. Their mothers — not always but often — talked to them about risk and danger. Their fathers said nothing. It was almost as if, once we stopped saying, "Don't do it till you're married," we didn't know what to replace it with. And we just thought, we aren't going to look.

I didn't like what those fathers were saying. I didn't think it was the right conversation to be having with girls. But I thought at least they're having some conversation and I can't say that that's true among my peers. I also think there's a lot of things our kids don't want to talk about. I think we have to normalize the conversation.

What I try now to do with my daughters [aged 16 and 12] is say, "You deserve to be with people who think you're great. Who think you're awesome. That's who deserves your company." And I talk about people and I don't talk about "boys," because fewer and fewer teenagers identity as exclusively heterosexual. I say that I want the people you date to respect you, to like you, to see how funny you are and I want you to have fun within that. And if it doesn't feel good for you, then there's something wrong.

I always say that this conversation that we're having about consent is so important. But consent is such a low bar for a sexual experience. We've got to do better than that. We have put a lot of emphasis on consent, because we should, but the for girls, sometimes they feel, "It ought to feel good because I said yes." And if it's not good, that's confusing and upsetting and hard to understand. We have to say, yes, consent, obviously consent, but consent is the baseline. It's not the experience. We are weird that as a culture we have become more comfortable talking about girls' victimization than girls' pleasure.

I have had a lot of conversations about this over the years with my nieces and my friends' daughters, and a lot of times I would give anything for the earth to swallow me up so I don't have to talk to them about orgasms. But I make myself do it. With one friend's teenage daughter I said, "I'm not going to tell you what you should or shouldn't do. I want you to think about these questions. Do you know where your clitoris is? Have you masturbated? Have you had an orgasm? With yourself? With him? Are you comfortable telling him what you like sexually?" A lot of adult women aren't comfortable with that. If what you're trying to do is express intimacy and mutual pleasure, I'm not sure that rushing to intercourse without understanding that pool of experience is going to get you there. So why are you doing it? I'm not saying it's wrong from a moral perspective, but from the perspective of understanding yourself and your sexuality and exploring, building agency and strength. Ask yourself those questions. It's so important for girls.

What do you think this generation is doing right? What gives you hope for change?

I had this conversation with a girl and she was saying that all the women in her family were super strong, and then she told me this litany of non-reciprocal experiences and I said, "Why did that happen?" And she told me, "Well, I guess girls are taught to be so meek and deferential." I said, "Wait a second, You just told me how strong you are." She said, "I didn't know that 'strong woman' applied to sex." But then she said, "I'm not doing any other girls favors by pretending these things are okay. I'm going to start going into my encounters demanding reciprocity and demanding respect, because otherwise these guys are going to think this is okay -- and they're going to keep doing this with somebody else too."

Shares