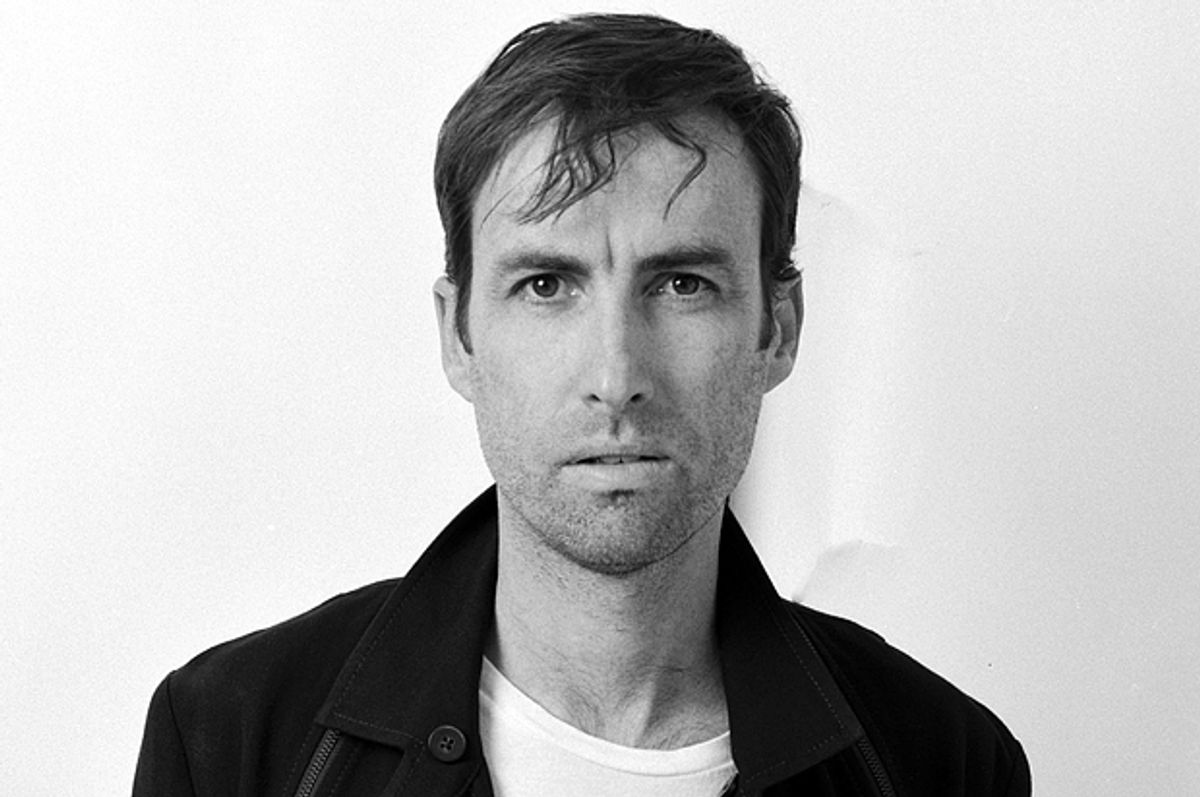

Despite going through conservatory and getting a degree in violin performance, Andrew Bird has always felt like an outsider in the world of classical music. Yet, as alternative acts were blooming around him in 1990s Chicago, he quickly realized he also didn’t belong in the world of confessional music that emphasized emotion over technical songcraft. Rather than give up, Bird built property on this seeming no-man’s land — a career based on his trademark violin, whistling and witty lyrics.

With those career hallmarks in place, Bird is setting out now on his new record, "Are You Serious," to deliver a sound that is more consciously polished and produced. Along the way, he’s finding that he has a bit more in common with the confessional cadre than he once thought — and that he’s more worried about democracy and guns than ever before.

This is a very strange time to be an American and to consider what democracy means with the election progressing, and I wondered if you had found any understanding of that for yourself.

I am searching for understanding. It's interesting; I was just looking at Salon last night, and there was an article that used the words I'd been searching for about Donald Trump, using the word "strongman" and "authoritarian," and that's what I'd been thinking. Like, wow, this is maybe one of the greatest risks to our democracy we've encountered. And that's all — who knows what's gonna happen? And I'm hearing from my friends, "Oh, if he gets elected, I'm leaving the country." I always have a problem with that one. Well, good for you. Save your own skin. Leave us all to deal with it. These are the things that are going through my mind.

I read that you're donating profits from your concert ticket sales to enrich gun control, and I was wondering specifically what organizations you're working with and how they're going about their efforts.

It's Everytown For Gun Safety, which is — I'm pretty impressed by them. They've got a really sensible message, which is kind of a voice that's needed, 'cause everything's so super-polarized on the issue. They're trying really hard to speak to the gun owners out there and not coming out with any threats to take away their guns or anything. Which is always the way I think. That kind of sensible voice is not always very popular, or, some would say, not always very effective. I just gotta believe that common sense can prevail sometimes.

So we're doing these [donations] through the concerts and then we're working on a video based on my song called "Pulaski at Night," which is about Chicago. Not written specifically about gun violence, but, as is the case with a lot of my songs, could be taken in many different ways. We're hoping that some of the imagery — it's gonna be shot in Chicago — and we're working on some concepts that will hopefully draw attention to the issue.

What do you think it will take to get us to a place where we have gun-related equilibrium? Or at least, we're not constantly having mass shootings?

Personally, I think it comes down to alienation and also kind of a warrior sensibility in our culture. It pervades a lot of aspects of American life, the need to project strength and control. Guns are very symbolic for Americans, I guess. 'Cause what are they, other than these things that shoot these projectiles? They're mechanical devices that throw something very fast through the air. I try to think of it in those terms. It's just this thing that does this thing; why is it such an obsession? And it comes down to symbolism and control. Security and strength, and all these things Americans seem to be pretty fixated on.

I think that the mass shootings — most of them, I don't know the statistics — but school shootings, that comes down to an amplified version of what we all probably went through in junior high and high school. Just taken to the extreme. When I was in sixth grade, I went through all sorts of vengeance scenarios to get back at the kids who were beating the crap out of me every day. None of them involved guns. The availability of guns certainly is a part of that. But I think the root cause is more about alienation and some of our social structures and institutional education — it's just too easy for a kid to get lost. There's more and more of us on the planet every day; there's more and more molecules rubbing against others, creating more friction and more scrapes out there. So it's just reaching a fever pitch. But certainly it is epidemic, more in America than other places. We gotta look at the way we have our whole society structured, really.

Did you go into making "Are You Serious" with any sort of goal or mission for yourself?

The previous couple of records were very scrappy by design. They were not very produced. I wanted them to be honest and just people in a room making music, and I wanted the sound to be natural, unproduced. This one, I wanted to embrace production for good rather than evil and really try to nail something. I wanted the process to be more rigorous than it's been in the past, and that involved reaching out to people and trusting more people around me. I really wanted to make a less whimsical, more visceral, grab-you-in-the-gut kind of record. I have all these grand schemes before I make a record. Usually, it's the antidote to whatever I'd done before. But I think in — I don't know how many records, ten, thirteen, it's arguable —I've never gone for it like this.

On the single, "Left Handed Kisses," hearing you and Fiona Apple singing together seems like it unlocks things in both of you that I don't usually hear in your music. How did that collaboration come about? Was it just done in a couple takes or did it take longer?

Well, the life of that song is really strange. Four years ago, I started writing this song where I challenged myself to write a simple love song, knowing that I was going to fail. But I wanted to prove to myself that I can write this love song, and I'm going to put "baby" in the chorus just to make it extra hard for myself. It's from the point of view of this skeptic, who nonetheless is trying to say, "Well, if I don't believe in these things, star-crossed lovers, that there's a right one out there for you, then how did I manage to find you in the multitudes?"

Then I had this other line in my head, this "left-handed kisses" line just popped into my head randomly and left-handed, back-handed, this voice in my own head sort of saying, "This isn't gonna fly; you sound a little [insincere]. If you really loved me, you'd take more risks." I do that a lot; I have a critique of my own song, and it becomes part of the song. It's a question of if it's strong enough of another voice to become another person and be a duet. I have a history of doing this.

I knew that the person with that voice would have to be really indicting and strong, and Fiona was at the top of a very short list. Next thing I know, we're in the studio recording it, and then a couple months later we're on daytime television doing it on "Ellen." Kind of a trip, that a song that complex and strange that doesn't push all your pop buttons and relies simply on the rawness of the dialogue. It really is like a short play.

I watched your TED Talk again last night and also thought about the pieces on songwriting you'd written for "Measure for Measure." You don't consider yourself a confessional songwriter, but you're willing to expose these parts of your process to your audience. What makes you feel comfortable inviting people in behind the scenes?

I don't know what it is about me. I like to take the myths out of things. I know people say "You're gonna demystify it or take the mystery out of it," but I don't think there's any risk of coming close to doing that. I like the dialogue with the audience. I often debut songs before they're finished and say, "I don't know if it should go this way or that way. What do you think?" And it's not like I'm gonna have people leaving comment cards on the way out or anything like that, but it's just the idea of being open because I don't like to come onstage with attitude or the feeling that I've got it all dialed in.

I always walk onstage thinking, "Oh my god, what's going to happen? I don't know what I'm doing." It's not lack of confidence. I totally do know what I'm doing. It's just that's something that works for me, the shoulder-to-shoulder, the connection to the audience somehow.

You got your start in Chicago in the '90s, and I was thinking how Liz Phair, Smashing Pumpkins, Urge Overkill and Material Issue were all also part of the Chicago scene of that decade. How much of that did you soak up, or was it totally separate from what you were doing?

I was definitely around it, but I felt like a total outsider in that scene. I would go to Lounge Acts and Empty Bottle and see these bands, and that's kind of where the title for this record comes from. I was coming from this — I guess "trained" is not the right word because I was never a good student — but I did go through conservatory and got a degree in violin performance, so that kind of qualifies me as not-your-DIY musician. But I was fascinated by that scene because it was so determined to be "It's not about how well we play; it's all about the emotion." Despite my background, I identified with that. I never fit into the classical world.

But I also had a little disconnect because I was into comparatively more fancy music than this raw, post-rock, or the Liz Phair confessional thing. I would think, sometimes, as I'd see someone singing about their pain, I would think, "Man, are you serious? Are you serious? If you're serious, you're gonna have to back this up every night, night after night." And I just couldn't identify with that sort of confessional thing that was going on, that still goes on. Then I named this record that because, after all these years, I find myself doing that or some version of that. It's still done on my own terms, but it's still processing some crazy, heavy stuff that happened to me. That was a very foreign idea to me when I was younger.

What do you think you would be if you weren't a musician?

I'm not good at much else. It's always been my job, though I was broke for many, many years. When I was younger I wanted to be a psychiatrist because I liked the idea of having a wood-paneled office. I liked the furniture. I was interested in listening to people. I might have been good at that, but I didn't do well in academia either. I'm just not a methodical person, so I'm just a bit haphazard.

That question came from listening to you talk about loops in the TED Talk — I wondered if you had any scientific leanings.

My theories are a bit more in the crackpot realm. I like to get to the big, big idea, even if my science is reckless. Like the TED thing I talked about, what is feedback? What is a feedback loop in nature, talking about mad cow disease and all these fascinating things that are kind of gross that we aren't really discussing as a people. I'm interested in those things where there's something there that we haven't gotten to the bottom of, but there's something there that tells us what we're made of.

Shares