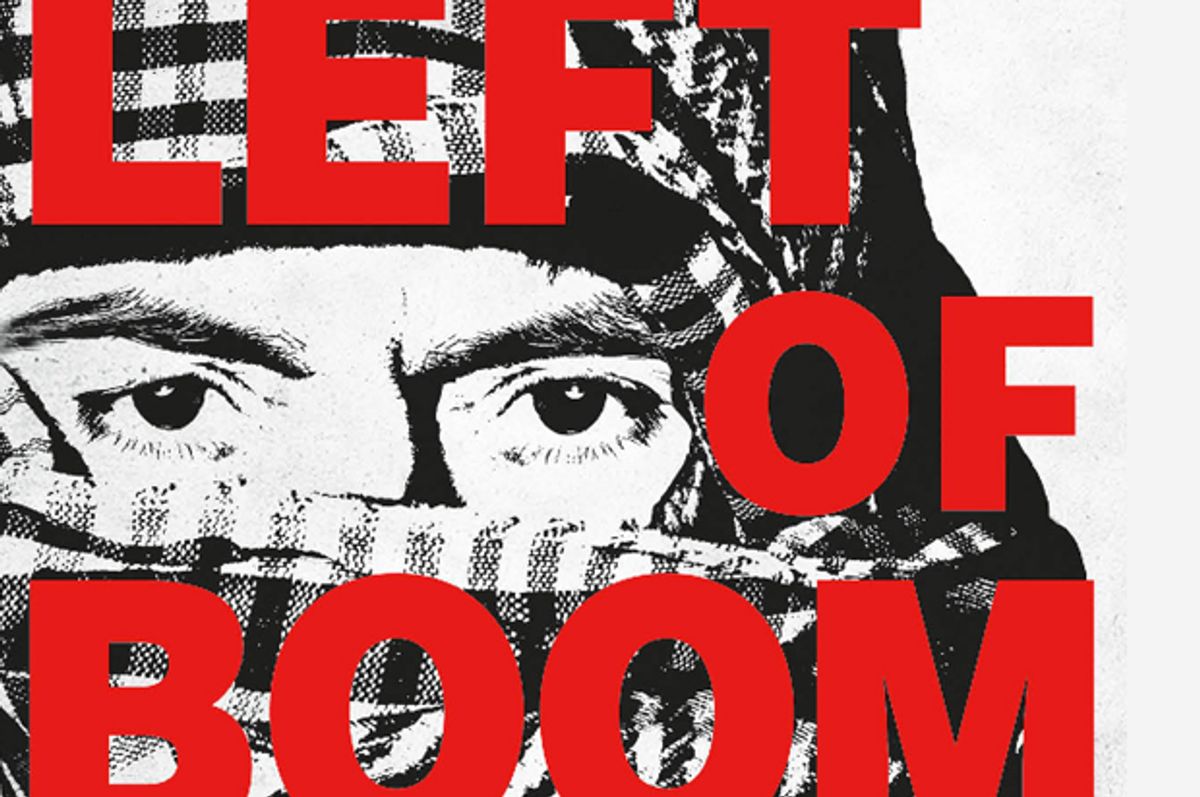

For a book that’s clearly been under the censor’s knife – words, sentences, entire paragraphs are blacked out -- “Left of Boom” is a very revealing document. Subtitled “How a Young CIA Case Officer Penetrated the Taliban and Al-Qaeda,” the book follows Douglas Laux from his hometown in rural eastern Indiana to the Middle East. And while the CIA has excised classified material about his missions in Afghanistan and Syria, his descriptions of his life stateside – constantly coming and going, dodging questions from friends, lying to girlfriends – are powerful and raw.

Alongside the pain, much of the book has an understated, self-deprecating humor that makes it intensely readable. It’s both a CIA memoir set in the Middle East and the story of a confused young man in his 20s.

Eight years in the agency, which included a tour in Afghanistan during the Afghan surge and another to Kandahar during the operation that killed Osama bin Laden, left Laux at times energized by the work, at times frustrated by the CIA bureaucracy, and sometimes self-destructive. He lost friends and colleagues. During a break between Middle Eastern postings, he fell hard into alcohol and OxyContin. He’s also critical of President Obama’s Syria policy.

Publishers Weekly called “Left of Boom,” written with Ralph Pezzullo, “a fascinating and engaging look inside the fast-paced and dangerous daily workings of today’s CIA.”

Salon spoke to the Washington, D.C.-based Laux from an undisclosed location. In conversation, Laux doesn’t come across like a macho boaster or a disgruntled officer with an axe to grind. He’s surprisingly humble, cautious, and almost soft-spoken. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

You were a guy who couldn’t pick out Afghanistan on a map, right? And then 9/11 made a huge impact on you.

Absolutely. I had planned to be an eye doctor when I first went to college. There was no Silicon Valley, nowhere people from the Midwest aspired to be. Now everybody wants to be an entrepreneur. I had done pretty well in high school, and got into a decent university. I set my goals pretty high: I figured I’d be a doctor or something. And then 9/11 happened and I immediately threw all of that out the window, realized I needed to start understanding the world I was living in. It wasn’t all my little bubble anymore.

A lot of the most poignant parts of the book show you dealing with girlfriends, not being able to tell people what you really do for a living. What’s that like? It must be brutal to have to lie to people close to you.

I always found that the most poignant part of the book, too, but over the last week the entire media has cared about one page about Syria.

And it is, and it’s why a good majority of my book. Every CIA book I had read previously – from all of the top director guys – I wondered, “Did we go through the same CIA? Where’s your personal life story? Share that!”

And I get it – a lot of them were married, and it was about raising children overseas. But I thought, that’s pretty pristine. It sounds like Mayberry. It sounds fantastic – I’d love that! Because that’s not what I’m experiencing: This is really, really, really hard.

I think I lay it out in the book: The CIA by its nature is insular – it has to be. It’s a secretive organization. That’s great.

It’s sort of built into the mission – not really any other way for them to do things…

I grew up in the CIA. Some people have come to calling me “Spy Kid.” I really became a man through the CIA. Even social experiences on the outside – whether it be with girlfriends or just friends, dealing with adult concerns now that you’re out of college – it was all new for me, too. You think of someone with a sales job, and what’s hard for them. It amplifies a couple levels when you’re lying to everybody, keeping secrets, trying not to reveal your true identity.

So the easiest thing to do is to only hang out with other clandestine officers – people who already are in the know. It’s what a lot of people choose to do, and I understand why. But as you can probably pick up from the book, my personality’s pretty strong, and I still wanted to have a very robust social life, as a single 23-year-old. I brought a lot of it on myself by making that decision.

Let’s talk about your life in the field a little bit. What made you successful infiltrating the Taliban and Al-Qaeda?

Two things. The foresight for them training me in Pashtu was very smart – I do want to give the CIA credit for that. I talk about frustrations, but then as I matured, and looked back, I saw that my knowing Pashtu was really, really reaping benefits.

Another was just persistence. I wasn’t there to check a box. I wasn’t there as a career move to help me advance. It looked at it as, “I’m going to do this regardless. It’s service to the U.S., not to the CIA.” You can tell, I’m a stubborn guy, I just stayed on target until mission complete.

What did you learn about the psychology of people who go into terrorist groups? Did you get a sense of what motivates them?

That’s an interesting question, because whether it’s Al-Qaeda, or Taliban, or ISIS, you’re talking about terrorist groups… You gotta ask what motivated them to begin with. A lot of people wish there was a silver bullet, or a simple answer: "Why do they hate us?," a lot of people ask me.

The best, most perfect analogy is that terrorism is a lot like cancer. In that, cancer is a catch-all term for a lot of different diseases that are not really related. A lot of the media used “terrorism” because it’s complex.

With terrorism, some of these guys are motivated because they’re sociopaths: That’s a good majority of them. Others because they were simply bored. Or because it was the thing to do. Or because, “My best friend joined, so I joined.” Or, “I wanted to experience some action, some adventure.”

You tell this to some Americans and they say, “Oh, bullcrap, it’s all Islam.” Certainly for some, they take the hard-line stance. But in my perspective – and I’m not speaking for CIA, it’s just my opinion -- from the guys I spoke to, Islam was often in the backseat.

I go and I learn the Koran, and translated it into Pashtu, because I thought I’d have to be so religious with these guys, and pray with them five times a day to get intelligence. But it was, “Now what can I do for you to get paid today? Brother, I’m struggling, I haven’t eaten in a while. I don’t feel like praying today… Let’s move on to me getting paid."

Everyone takes the perspective that I was so frustrated and couldn’t no longer tolerate President Obama, or Hillary Clinton, or pick your poison… That’s not the case. If you get to the final chapter, you see I went to the senior guy in charge me and said, “I’m having a hard time – what do you think I should do.” And he was open to me.

I want to be clear: The CIA never pushed me out the door. It was, we’d love you to stay but if it’s not for you, Doug, it’s best you leave now.

I brought upon myself all the stress: I insisted on keeping it at 11 the entire time. What happened to me is not indicative of what happens to every CIA officer. A lot of them manage their stress a lot better than I did. I just got to a breaking point.

As far as what they can do: This is how it has to work. This is a bureaucracy. What are you gonna do – privatize intelligence? This is how it works. It took me this long to gain that perspective. I was happy to get the opportunity to serve, and now I’m gonna go do something else.

How much did your life resemble the show “Homeland?”

Really, the only similarity is that we were both in the same country, and may’ve spoken some of the same language. But I’ve watched the first episode – that’s the only one I’ve seen -- and it made me laugh. I’m not disparaging it, I hear it’s a great show and it’s very compelling.

It’s exaggerated because it’s exciting and it sells tickets. I’ve seen every Bourne movie and every Bond movie. That doesn’t mean I can relate to any of it. But they’re enjoyable.

I imagine the actual spycraft is a lot slower than in a movie.

The tradecraft what we call it – it’s a lot slower and a lot more methodical.

For instance, you see Carrie in the pilot episode running around, calling the assistant director of the NCS [National Clandestine Service] – I’m like coughing! If I was drinking milk it would have shot out of my nose. She’s a case officer! That’s 7,000 layers above her. She would never… and on an open line, by the way, from the Middle East…

Paying an asset, in public, in front of a hostile government’s building… All the stuff that to us is so obvious and laughable.

People say, “You really remind me of Carrie.” Hey, I don’t take that as a compliment at all. I’d also not seen the show “True Detective,” but people told me I reminded them of this guy Rust, played by Matthew McConaughey. I was like, Wow, that’s two for two in the dark realm, there.

Shares