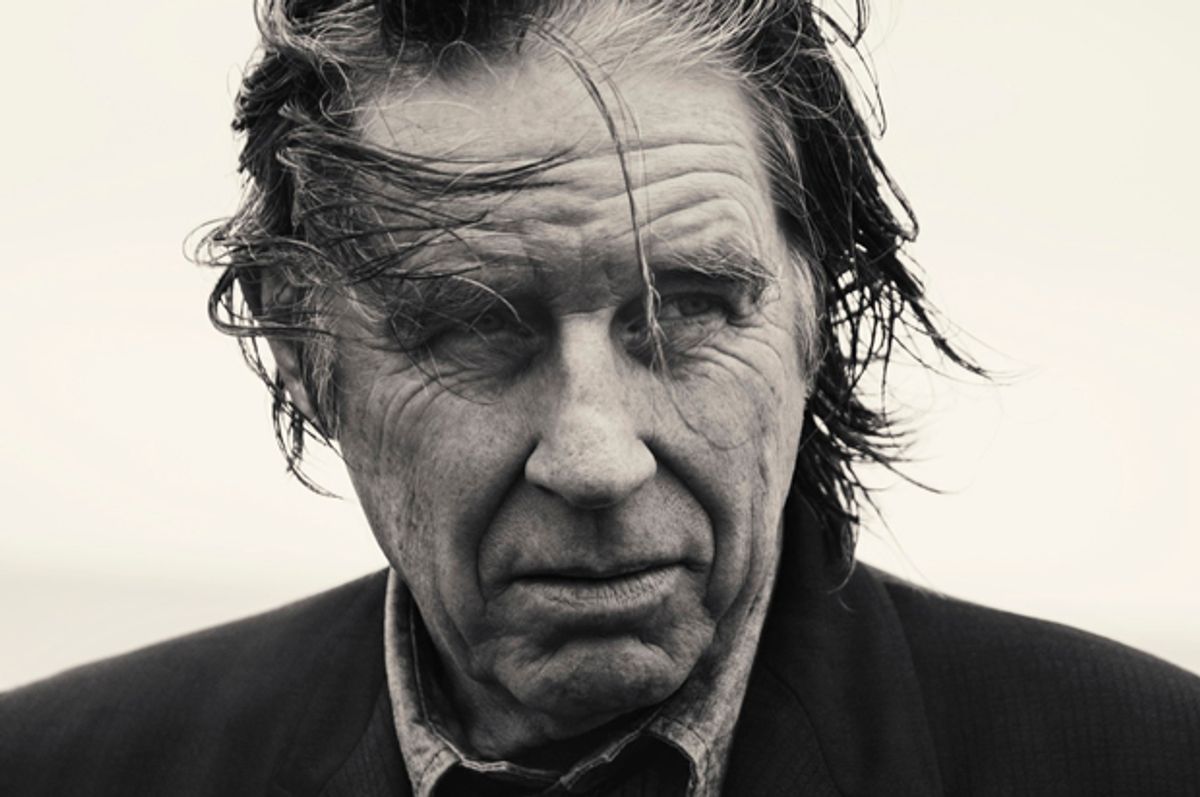

For four decades, John Doe’s been the sturdy and surly voice of Los Angeles punk, as singer and songwriter in the genre’s finest band, X. His lengthy solo career has revealed him to be more of a wanderer, exploring various sounds and landscapes. He’s also been a hard-working character actor and poet and will release his new book, "Under the Big Black Sun," (also the title of X’s classic third album) a collaborative memoir, in May.

For his new album, "Westerner," Doe ventured to Tuscon, Arizona, home of his late friend Michael Blake (screenwriter of the Oscar-winning epic "Dances with Wolves") and the studio of producer and performer Howe Gelb of Giant Sand, to achieve his unique rootsy, spacious quality. The result recalls the quieter Doors, various psychedelic Nuggets and a healthy amount of Americana folk.

Here, Doe discusses the album, the book, the West and X’s upcoming fortieth anniversary (yes, fortieth anniversary).

You’re originally from the East Coast, but you’ve been on the West Coast for about 40 years now. Do you identify as a “Westerner”? Compared to the East Coast, it’s like a different planet out there.

[Laughs] Spoken like a true Easterner.

I love Los Angeles, but I feel like I’m from space when I visit. Do you feel like a native? Is the title of the album autobiographical?

Yes, it is. I identify as a male, first. [Laughs] I’m joking.

What is it about the West that you identify with?

Any place that has that kind of vista and horizon. That’s what first struck me about it. But I would agree with you: Los Angeles, especially the emotional state that it puts me in now, is totally another planet. A lot of it had to do with the space and the light. When I first went to L.A. in early ‘76, it just hit me like a brick, just walking out of the airport terminal.

There’s a certain texture to the album that reminds me of space and sky and heat. It feels geographically specific.

I’m glad that translates, because it was intentional. That’s why I wanted to work with Howe. I think "Hal" has done a really great job in refining that kind of sound.

What does your late friend Michael Blake mean to the record?

Michael and I met probably 30 years ago. He’s most famous for writing “Dances with Wolves.” He wrote the story and the screenplay and won an Oscar for that, but he also wrote several other historical fiction books that were really simple and all about telling a story. His favorite writer was Jack London, and he was in somewhat the same camp as him. Michael wasn’t quite the adventurer. Michael and I were like brothers. We talked about art, we talked about writing, we talked about everything, our relationships, character or narrator, in most of the songs. The songs are autobiographical too, it’s not just about him.

The Native American presence in the Southwest is palpable.

I would say that’s what he dedicated his life to. Some people don’t like that movie as much as others, and some people like to poke fun at it. But regardless of your opinion of the movie, it completely changed the modern perception of what Indian culture was like at the time. Before that, it was pretty simple. That was such a commercial success that people had to look at Native American culture in a different way, like, “Oh! Shit!” It’s come around. I really think that Michael is still helping me with this project. It sounds very “woo-woo,” and I don’t care, to be honest. [Laughs.]

I saw this image that’s on the cover, and that is also helping Native American causes, because it was a collaboration between Aaron Huey and Shepard Fairey. The photograph was taken up at the Rosebud Reservation, and it’s helping that cause, called “Protect the Sacred” or “Honor the Treaties.”

Does playing music allow you to open up more to those kinds of spiritual influences?

Yeah, that’s really true. I think it’s something that you either develop as you get older or you choose to ignore. Even though I’m not religious, I’m more and more spiritual. I believe in spirits and I believe in things that you can’t see acting on the way things turn out. Anytime you’re being open, anytime your guard is down, anytime you’re using the right side of your brain I think you’re more open to different ways of explaining things or experiencing things.

There are a lot of harmonic vocals on the record, almost reminiscent of what you and Exene [Cervenka, of X] would do. Was this intended to bring out a certain quality?

Yeah. Exene and I taught each other great lessons. Exene was also a true friend to Michael, and he actually patterned the main female character in “Dances with Wolves” after Exene and dedicated the book to her. I like singing with somebody else, and I’ve done that a lot.

Which song is Chan Marshall on?

She's on that song “A Little Help.”

And Debbie Harry is on “Go Baby Go.” In Blondie, she is usually a lead singer, but here she’s definitely a little bit more in the background, which was interesting. What was that like in the studio?

Debbie is a great singer, but, like you say, she’s not used to singing harmonies that much. So she was asking me, “Is that OK?” And I’m saying, “Look, you can just read the phone book and it’d be fine." It took her a minute to understand and get the line, but then the crazy thing is, she said, “Ok, well, what if I just doubled that?” And I thought, “Sure, why not?” And she did it in one take. It was like she knew exactly what she’s done. And if you think of Debbie’s voice on a lot of Blondie stuff, a lot of it is doubled. So she knows that like the back of her hand. So it took her maybe 45 minutes to work out the part and to get the phrasing right and stuff like that, but then, once that was done, she doubled her own voice in, like, one take. It was insane. It was like totally uncanny. Like, “What did I just experience?” And that was pretty awesome.

Have you known her for a long time?

Well, yeah, we met a long, long time ago, and then X was lucky enough to do a tour with Blondie; I think it was 2012. She was coming over to our dressing room quite a bit because she really wanted to hang out with Exene, and we kind of hit it off, and I asked it if it would be OK if I called her when I was making a record. Then I found that song, and that song has kind of a '60s garage rock n’ roll vibe to it.

There are some sparse songs and some rockers on the album. “Get on Board” really reminded me of The Doors.

Really? I take that as a compliment.

I’m thinking of the scene in the Oliver Stone film where they go to the desert to take peyote and commune with the spirit world. You have a connection with The Doors through Ray Manzarek, your old producer. Did you think of them at all when you were working on this?

I was a big fan of Jim Morrison — his ability to channel that Dionysus thing that people have written about a lot. Someone just asked me about The Doors because I did a tribute to Ray. The question was, “Why did The Doors get a pass in the punk rock world?” And I said, “Because they just represented chaos and they didn’t give a fuck about anything and they were really dark.”

Brendan Mullen once told me that it was because Iggy Pop was such a Doors fan.

[Laughs] Yeah. But to answer your question, about whether I did think of The Doors: It’s just there. I don’t have to. On the other hand, in that song: a little bit, but more so in another song called “My Darling, Blue Skies.” I heard some of Ray Manzarek (Doors keyboardist and producer of classic era X albums) in the organ. I heard some of The Doors in, just, the beat of it. It sounded a little bit like “Break On Through.” So I thought, “Yes, let’s go for that more.” I’d give a nod to The Doors on that, “My Darling, Blue Skies.” Maybe if you listen to that again you’ll hear it.

How did Ray Manzarek’s death affect you?

It hit us pretty hard. I thought of Ray as kind of a father figure or, at least, a mentor. At the very beginning, we were completely dumbstruck that he wanted to work with us. It was a dream come true. I think the most difficult part, which would be for anybody with any close, or just a friend passing, it seemed really sudden. No one ever said, “Oh, by the way, Ray’s sick.” Somebody kind of mentioned it to me at a gig and said, “Oh, I heard about Ray.” And I said, “What did you hear about Ray?” And then three weeks later he was gone.

The album’s been getting a lot of attention. You’ve seen the business change; is it easier to be heard now?

I don’t know. I’m confident that I’m going to do as much as I can and I’m confident that I’ve made the right choice in working with Howe Gelb, and I give him a lot of credit, along with Dave Way, who mixed it. But the biggest challenge now is to rise above the static. There’s so, so much going on. I think it is harder, but I also don’t care ... there is no breakthrough, there.

Some people thought that there were X songs that should have been big hits and they didn’t end up getting played on Top 40 radio.

Because we were still too weird. You know? People like The Pretenders or Nick Lowe or Elvis Costello, they were a little bit more like ... people could wrap their heads around it, but we were just too weird, and that’s fine.

Tell me about your upcoming book, “Under The Big, Black Sun: A Personal History of LA Punk.” Which is obviously the title of an X record. Is it a memoir or is it more poetic?

It’s a memoir, but I didn’t do it on my own, mainly because the L.A scene was so collaborative. I used that same sense of collaboration. I wrote four chapters: the beginning, the middle and the end, and then a bunch of inner/additional pieces. Then I enlisted Exene, Henry Rollins and Mike Watt, Jane Wiedlin and El Vez and Dave Alvin, all different people that had been in the scene at the time, and asked them to write a chapter, so they had three to 5,000 words to tell their story. But I also gave them a topic, because I felt like they were expert in certain things .

What’s the status of X now? Is Billy Zoom’s health OK? [Zoom was recovering from cancer.]

Billy’s health is good. We’re playing a little less this year, just so I can work on the solo record. Because we played quite a bit last year, and then 2017 is our 40th anniversary, so we’re going to do a lot of stuff then. I don’t know if we’ll record, but we’re going to be touring live, and we’ve got a different kind of set going on now, where we call it “in concert,” so some of it is a little more sit-down oriented. But then we also play loud and fast, and so it’s a broader range of X.

40 years is really something...

I know. I know! And you know what? Five years ago, 10 years ago, I would’ve said, “Oh my God, that’s so long.” And now it’s celebratory, so you have that to look forward to. I’m assuming you’re younger than I am. After you pass a certain milestone of either age or your perception, it’s like “Yeah! Fuck yeah!”

Shares