Looking beyond the daily tussle between Donald J. Trump and the Republican Party, or Bernie Sanders and the Democratic Party, let’s consider the larger historical picture to see what the current election campaign tells us about the state of the two major political parties and their future.

Over the last forty years both major political parties have been in a state of terminal decline for a number of reasons, primarily the ideological contradictions each has developed quite in sync with the other, driven by the same economic trends. Both are in a death spiral at the moment, but this being America, where political accountability is not as rapid or conclusive as in Europe, it’s likely that they will continue in more or less their existing forms for the foreseeable future, further deepening the crisis of legitimacy. Whatever the realities about their loss of credibility, we are not likely to hear an announcement anytime soon that the Democratic or Republican parties are dead, having ceased to serve the respective functions for which they accumulated much legitimacy at different points in the twentieth century.

It may seem, with stronger party identification over the last couple of decades, that the parties are stronger than ever, but this would be misleading on several counts. The fact most frequently cited in support of the parties’ strength is increased polarity in Congress, where in recent decades members of each party have moved farther toward the extremes, which means less bipartisan consensus. The electorate has sharply divided, with left and right divisions more pronounced, amidst the now familiar phenomenon of the red state/blue state split which first became prominently visible in the 2000 election.

But it would be a mistake to confuse ideological polarity with party loyalty. In Congress, members have no choice but to support the party closest to their ideological leanings, and likewise for the populace at large. Third parties have had a difficult time getting off the ground in America—what should have developed into a breakaway anti-corporate party after the Seattle WTO protests in 1999 and Ralph Nader’s candidacy in 2000 never happened—so the lack of party choice at the national level creates the illusion of strong party support.

The last time the establishment—both Republican and Democratic—publicly bemoaned the loss of legitimacy for government, which included the state of the parties, was in the 1970s. This was a persistent theme throughout that decade, after the landslide McGovern defeat in 1972, and the ouster of President Nixon in 1974. An impression was perpetuated by the elites that the U.S. was on the run against communism on all continents. After the 1973 oil embargo, and the stagflation that lasted throughout the decade, Keynesian policy—the glue that had held the New Deal coalition together for decades— swiftly unraveled. The crisis was deep and sustained, both domestically and globally, and the parties and their allied establishments seemed to have their days numbered.

Bizarre and illogical compromises began occurring at that time to preserve the sanctity of the parties, and of the narrow liberal-conservative identification, awkward arrangements that are bearing full fruit only today.

On the Democratic side, President Carter began nudging the party in the direction of corporate, free trade, tight monetarist policies that were later to find their most optimistic rendition during Bill Clinton’s administration. The recession of the early 1980s, which coincided with President Reagan’s first years, was actually launched by Fed chairman Paul Volcker under a Democratic president. The invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union led the Democratic party down a renewed path of militarism—although during the 1970s and 1980s often by proxy means rather than direct intervention—that reached a crisis point in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But all this provided only a patchwork solution to the Democratic party’s crisis of legitimacy. Was it a pro-corporate (neoliberal) or pro-labor (New Deal) party? The actual tendency was for the party to move firmly in the former direction, while escalating rhetorical claims for the rights of cultural minorities, at the same time as the Republican party moved swiftly toward a neoconservative solution to its own crisis. Meanwhile, the Democrats never really addressed the popular roots of dissatisfaction: in a global economy with more dispersed power, both economic and political, how was the standard of living of the American middle-class to be maintained?

The huge popularity of Bernie Sanders on the left today speaks to precisely this dilemma, fundamentally unaddressed through four decades of deceit and illusion to maintain elite power, as inequality continuously rose in that period of time, the middle class became ever more diminished, and real political power became confined to a vanishingly small elite group.

The Republican establishment, over the last forty years, pursued a parallel, and often intersecting (especially in times of war and recession), path as the Democrats. Although Ronald Reagan didn’t make it all the way in 1976, because the wounds from Nixon’s ouster were still too raw, their own patchwork coalition—nationalist and militarist, beholden to the myth of the free market and personal responsibility, and committed to pulling back the hard-won social and economic rights of the minorities and the poor—proved to be a winning one for a long time.

It meant that the Republican elites had to put up with a lot of sound and fury about cultural issues like abortion (to feed the evangelical beast), while having a free hand to accumulate the same kind of power, economic and political, within an increasingly smaller elite’s exclusive grasp as was the case with the Democrats.

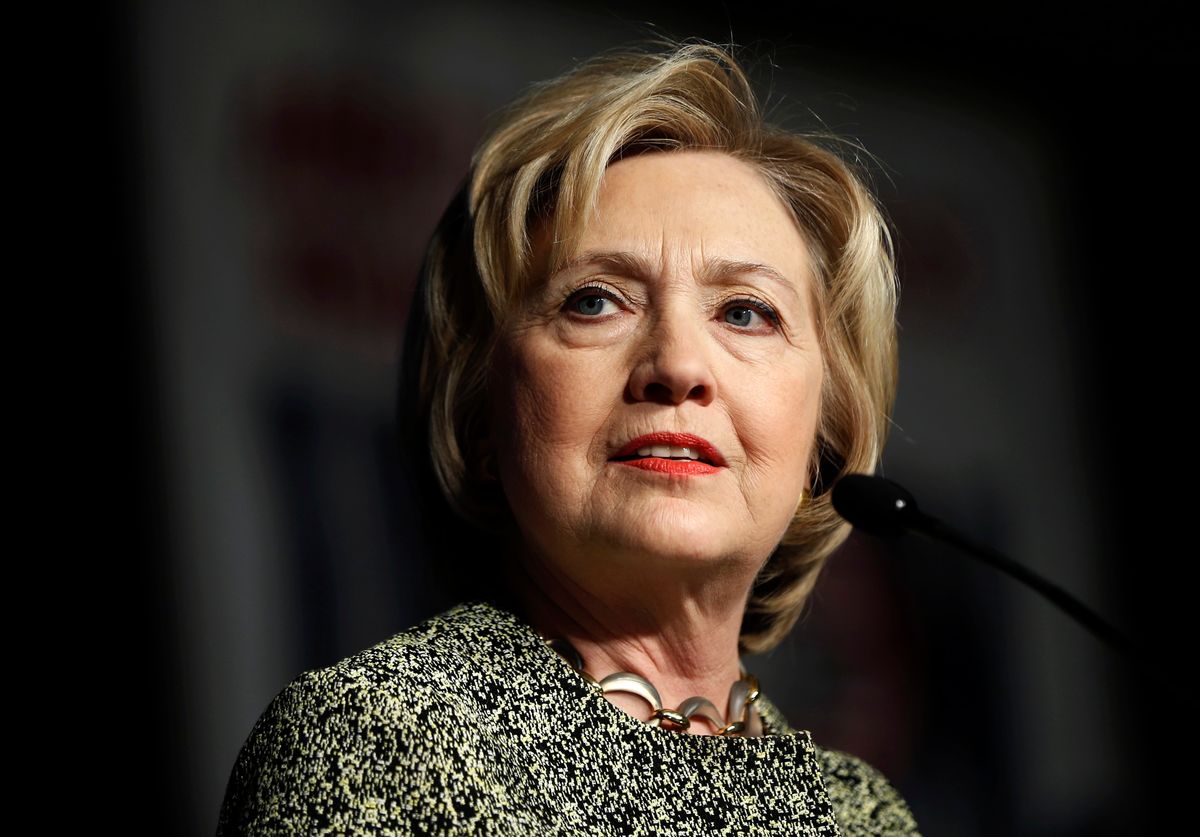

In time, particularly with Bill Clinton’s “new democrat” retreat from what remained of the New Deal commitment, the gap between the two establishments narrowed, often to the point of invisibility. Think, for example, of the merger of sensibilities right after 9/11, when Democrats and Republicans unified around reneging on civil liberties and authorizing illegal actions in war and at detention sites. The same unification of the elites occurred in the prelude to the Iraq war, and in the aftermath of the financial collapse. Barack Obama started off being open to a “grand bargain” to further deplete the remaining social safety net in the name of fiscal responsibility, and one can expect Hillary Clinton (like Jeb Bush, had he been the nominee) to be on the hunt for similar grand bargains. Each crisis makes the uniformity between the parties manifest, which riles up the populist base on either side to even greater degrees of frustration.

Trump’s heresy is to point out, as he did in a recent debate, that the Iraq war was based on lies, and that George W. Bush did not keep us safe. These are obvious facts, but they are not uttered in Republican elite circles. Jeb Bush, as a result of the truth-telling, and the capacity of the failing middle class to see through the establishment’s fog of confusion, stood discredited, as is increasingly the case with Hillary Clinton, whose every defense of Bill Clinton’s punitive neoliberal policies on crime and welfare and civil liberties makes her husband’s administration transparent as the sordid hodgepodge of concessions to corporate hegemony that it was.

The Republican party can no longer keep its disaffected constituents under control either; under various guises—the silent majority, the Reagan Democrats, the Tea Party, and now the Trumpheads—they have been making their presence felt again and again, though for four decades the party has been able to keep diverting the subject, particularly with national security anxieties. Likewise, the Democrats cannot keep their old faithful on the reservation, who also keep making their anti-corporate sentiments felt, mostly recently with the Occupy movement and the Sanders upsurge. They are the same ones who trusted that Obama would weaken the corporate stronghold, but were quickly disillusioned when he did no such thing; and the ones supporting Trump are generally the same kind of people who went with Ross Perot in an earlier time as he raised hell about NAFTA’s impact on American industrial jobs, or with Pat Buchanan as he stoked white nationalist resentments.

I suspect that if the half of the population that doesn’t vote were to do so, most of them would fall in line with either Trump or Sanders; these are the ones who are so disillusioned, or disempowered, that they do not even bother to participate. Both parties have long since left them. In this sense too, the statistics cited on behalf of strong party identification, or ideological polarization along strict party lines, are illusionary.

Again and again, the establishment has been able to paper over the underlying crisis of legitimacy with artful means designed to hoodwink people. Reagan’s morning in America, Bill Clinton’s new economy, George Bush’s war on terrorism, Obama’s hope and change, and on it goes, with what would have been—and perhaps still will be—Hillary Clinton or Ted Cruz’s new social alignment (a further strengthening of the neoliberal wise on what little remains of freedom in America, with a theological veneer in the case of Cruz or rhetorical multiculturalism in the case of Clinton, but with the same overall effect).

This time, however, the people, both on the Democratic and Republican sides, can see through the strategy to divert attention from the hollowness of American economic and cultural life. It’s still a strong bet that the establishment—outmaneuvering Trump and Sanders through the arcane undemocratic operations of delegate allocation—will pull through, for yet another eight years of war and economic misery and curtailment of freedom. The crisis will only fester with more malevolent outpourings slated for the future, until perhaps someone even more dictatorial than Trump comes along.

Had the elites chosen to be more democratic thirty or forty or twenty years ago, both parties would have naturally evolved and reshaped themselves in accord with shifting social and economic realities. Liberalism and conservatism, in their authentic manifestations, would have continued fighting the good fight, rather than the situation that has developed, where economic anxiety is continually suppressed and allowed to manifest only in twisted movements that have little chance of accomplishing any objectives given the present distribution of power.

It is noteworthy that a great many among America’s intellectual elite support Hillary Clinton over Bernie Sanders, offering standard neoliberal justifications, whereas those outside elite intellectual circles are more likely to support Sanders; likewise with Trump and his antagonists and supporters. What the establishment will not do is take either of them seriously; meaning that they will not, as they haven’t for forty years, acknowledge the concerns of the constituencies they are supposed to represent, and direct the very real anxieties felt on all parts of the political spectrum toward positive resolutions good for the country and for the rest of the world.

Shares